£50, a Bottle of Whisky, and Why Birmingham Still Knows Better

We live in a country where saving has been made to feel futile. Interest rates rarely beat inflation. Pensions feel abstract and insecure. Housing feels permanently out of reach for many.

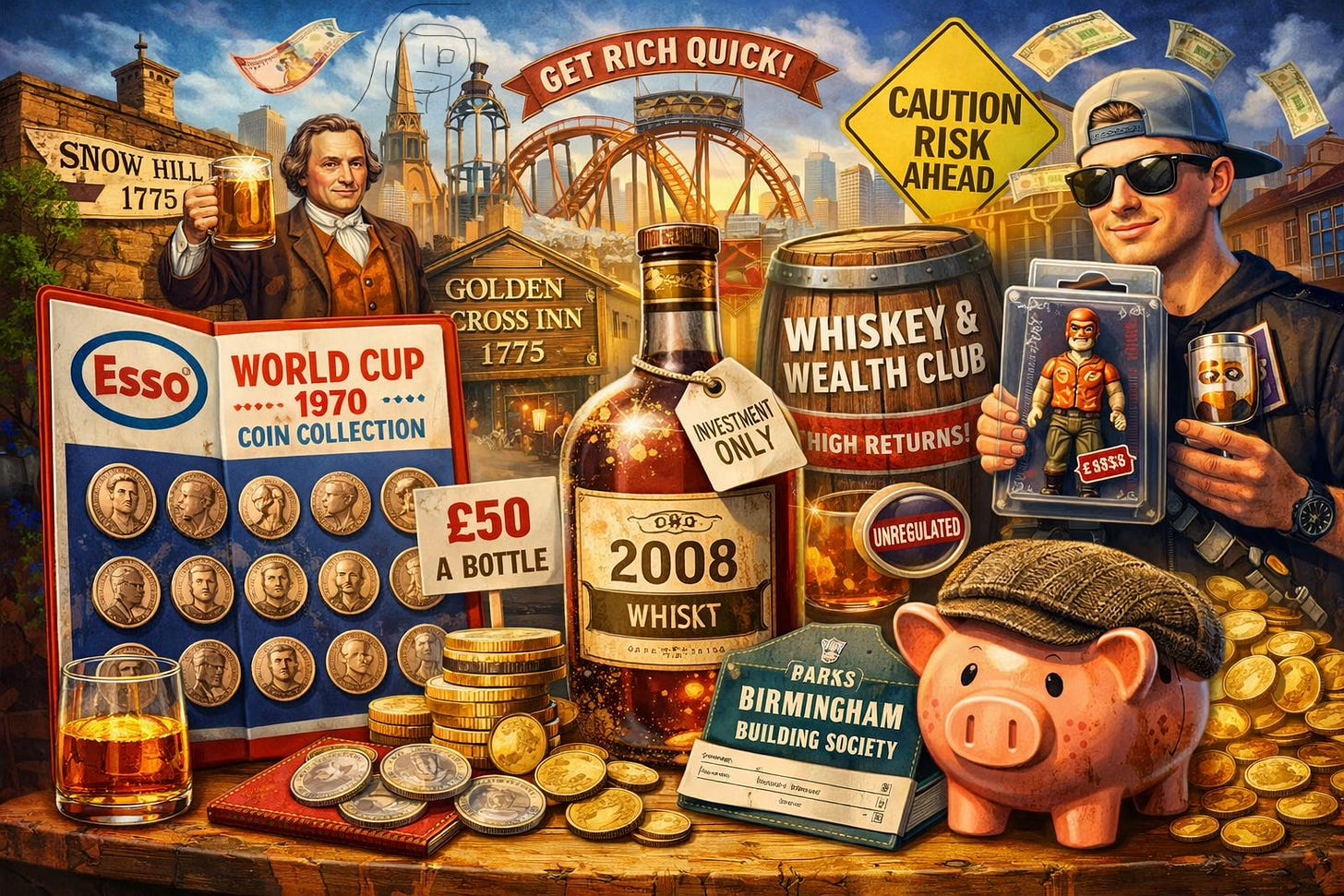

Birmingham did not invent get rich quick. It invented get housed slowly. Long before wealth clubs, lifestyle investments and projected returns, ordinary people in this city pooled small sums in a pub on Snow Hill to build homes, one by one, until everyone was housed and the scheme could quietly dissolve. That deliberately boring idea created more security than a thousand glossy adverts ever could, which is why it is worth remembering when modern investment culture starts selling whisky, plastic and nostalgia as routes to prosperity.

Against that background, my own contribution to the national investment debate is modest to the point of embarrassment. I was thinking of buying each of my grandchildren a bottle of whisky from the year they were born. Before anyone reaches for the phone to ring children’s social services, let me be clear. This is not encouragement to drink. It is not about consumption at all. The law, in its quietly British way, draws a distinction between buying alcohol in public and giving it as a private gift. A child cannot buy alcohol and an adult cannot buy it on their behalf in a shop or pub, but a parent or grandparent can lawfully give a bottle to be kept at home. It can sit on a shelf for years, untouched, gathering dust and stories rather than liver damage.

The idea is simple. If, by the time they are eighteen, the bottle has gone up in value, fine. If it has not, they can open it and share it round with a few mates. Nobody is ruined. Nobody has been misled. Nobody has been promised anything that reality is unlikely to deliver. It is just a bottle from their year, waiting patiently, doing what whisky does best, which is nothing at all.

It is remarkable how far this sort of thinking now sits from the language of modern investment culture.

When I was a child, Esso petrol stations gave away World Cup coin collections. They were delightful little things, especially against the backdrop of pre decimal coinage, which was functional but hardly glamorous. These coins shone. They came with a presentation album, and completing the set felt like an achievement, even if nobody could quite explain why.

You can buy the entire collection today, album included, in superb condition, for about thirty pounds. That is thirty pounds for the whole set. Not per coin. The lot.

This is not a complaint about lost value. It is simply how collecting works when nobody lies to you about why you are doing it. Nobody told a six year old in 1970 that Esso coins were an investment vehicle. Nobody talked about average annual returns or exit strategies. You collected them because they were nice and because England were playing football.

That distinction has quietly eroded.

My grandson shows me his collections now. Bear Brikes..!! Rows of strange plastic mouldings, sealed in boxes, graded, catalogued and priced in dollars. Why dollars, I do not know. We live in Britain. He tells me some are worth hundreds. I do not disbelieve him. I simply find myself wondering whether a wardrobe full of Chinese plastic is really going to buy him his first house, or even meaningfully contribute to a deposit.

This is not mockery. It is curiosity informed by experience. Collecting can be pleasurable. Speculating is something else entirely. The trouble is that modern investment culture has blurred the line between the two, dressing speculation up in nostalgia, lifestyle imagery and confident language until it feels like common sense.

Which brings us to whisky, wealth clubs and the Advertising Standards Authority.

Earlier this year, the ASA upheld complaints against Whiskey and Wealth Club, ruling that its advertising misled consumers about returns, failed to make risks sufficiently clear, and omitted crucial information about the unregulated nature of whisky cask investment. The ads talked about private investors, market insights and exit strategies. They quoted average annual returns of eight to eighteen per cent and even projected fifty five per cent under certain strategies. Risk warnings were buried, fleeting or absent altogether. The fact that the market was unregulated, with no Financial Services Compensation Scheme protection and no Financial Ombudsman oversight, was not made clear.

The ASA concluded that this was misleading. It is hard to disagree.

What matters more, though, is why such advertising felt plausible in the first place.

We live in a country where saving has been made to feel futile. Interest rates rarely beat inflation. Pensions feel abstract and insecure. Housing feels permanently out of reach for many. In that environment, the promise of a tangible asset quietly appreciating in the background sounds reassuring. A barrel of whisky ageing in a warehouse feels safer than a number on a screen.

That is precisely why clarity matters. When the language of finance escapes its proper boundaries and attaches itself to almost anything that can be sold as wealth, people begin to confuse solidity with safety and presentation with protection.

Which is why Birmingham’s history is more than a footnote.

The first known building society was founded here in 1775 at the Golden Cross Inn on Snow Hill. The landlord, Richard Ketley, did not promise prosperity. He gathered ordinary working people who wanted a home and could not get there alone. They pooled subscriptions into a common fund. Members drew lots to decide whose house would be built first. When everyone was housed, the society wound itself up.

This was the original building society model, known as a terminating society. No endless growth. No permanent sales funnel. No suggestion that housing was a game. Just shared effort, shared risk and a clear end point.

It could only really have happened in Birmingham. Eighteenth century Birmingham thrived on clubs, coffee houses, pubs and associations. The Midlands Enlightenment was not just about science and ideas. It was about practical cooperation, about asking how things could be built rather than how they could be sold.

Building societies were boring on purpose. That was the point.

Over time, the model evolved. Permanent societies emerged. Regulation followed. Mutual ownership became embedded. Building societies offered savings and mortgages owned by their members, one member one vote, not shareholders demanding ever higher returns. This was not glamorous. It was financial democracy, and it worked because it was slow, transparent and predictable.

Then, late in the twentieth century, we lost confidence in boring. Demutualisation arrived. Growth replaced purpose. Language shifted. And gradually, the idea took hold that excitement was a virtue and caution a failure.

Which leaves us with an awkward question.

When did we stop trusting the building society.

Why did regulated, mutual institutions born out of Birmingham pragmatism start to feel less attractive than glossy websites offering exit strategies on barrels of alcohol. Why does unregulated but expensive feel safer to some people than regulated but dull.

That is not just a financial question. It is cultural.

This is why my fifty pound bottle of whisky matters, despite being financially trivial. It is honest about what it is. It does not promise to outperform anything. It does not pretend to be a strategy. It is a marker in time, a story waiting on a shelf, and a shared moment deferred.

If it becomes valuable, that is incidental. If it does not, nothing has been lost. The worst case scenario is conversation and laughter.

My Esso coins did not make me rich. Nor were they meant to. They shimmered briefly, delighted a child, and now sit in someone else’s cupboard, occasionally glanced at, faintly remembered and correctly priced.

Perhaps that is the lesson we keep forgetting.

Not everything needs to be an investment.

Not everything needs a strategy.

And not every shiny object needs to carry the weight of our economic anxiety.

Sometimes fifty pounds is just fifty pounds.

Sometimes a bottle is just a bottle.

And sometimes the wisest thing you can do is trust the boring institutions, enjoy the small gestures, and remain deeply suspicious of anyone promising otherwise.

Birmingham knew that once. It might be time we remembered it again.

And this is why I have never gone further than putting my savings in the building society, and buying books I actually want to read.