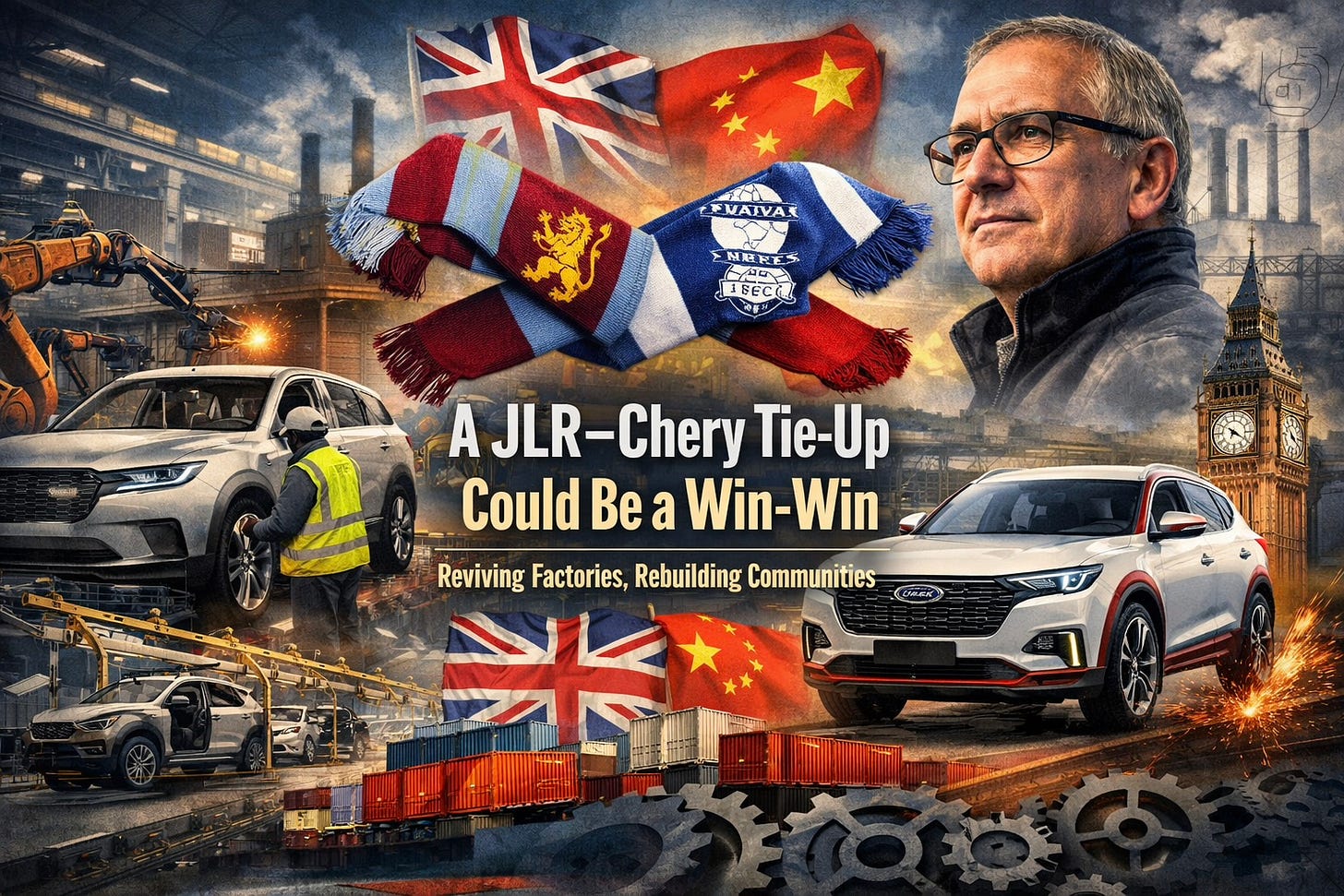

A JLR–Chery Tie-Up Could Be a Win-Win

Why idle factories are a luxury Britain can no longer afford

I grew up inside a working factory economy. My factory opened at 7.30 and shut at four, Monday to Friday. Overtime when demand required it. Rates paid whether the machines were running or not. The company van stayed the company van at weekends because it belonged to something bigger than the clock. We lived off the supply chain, contracts from Ford, Black & Decker, and a host of British manufacturers that once stitched this country together industrially. What mattered was utilisation. If the plant was busy, wages flowed, skills deepened, communities held together. If it was not, decline followed. That truth has not changed. What has changed is the cost of ignoring it.

That is why the argument advanced by Birminghams own brilliant super mind Professor David Bailey matters. He is not talking about a utopian future or a reckless global free-for-all. He is describing an intelligent industrial world, one where we stop pretending that billion-pound production facilities can sit idle for most of the week without consequence. His insight is simple and quietly radical: modern factories are too expensive, too strategic, and too important to national resilience to be treated as single-use assets in an era of volatile demand.

Think of it like this. Imagine Aston Villa and Birmingham City sharing a stadium. Emotionally impossible, of course. Economically absurd not to consider, if the ground otherwise sat empty most of the time. Strip away the tribal baggage and the logic becomes unavoidable. That, in essence, is the territory we are now in with manufacturing.

Idle capacity is not neutral

Automotive plants are among the most capital-intensive assets on the planet. Buildings, robotics, tooling, energy systems, digital infrastructure, and a highly skilled workforce all represent fixed costs that do not politely wait until demand recovers. Profitability depends on running close to capacity. When lines slow or stop, overheads do not.

Electrification has made this worse. Model cycles are shorter. Demand is unpredictable. Re-tooling takes time and money. Plants can find themselves technically available but economically stranded while companies bridge from one platform to the next.

For Jaguar Land Rover, spare capacity in its British plants is not latent opportunity. It is stranded cost. Leaving that capacity unused two-thirds of the time is not conservatism. It is industrial self-harm.

This is why reports of a possible arrangement under which Chery assembles selected models using surplus capacity at JLR’s UK plants should be approached with seriousness rather than reflex alarm. Similar models already exist. Stellantis builds Leapmotor vehicles at its Tychy plant in Poland. The idea is no longer exotic. The only question is whether Britain chooses to participate intelligently.

Who are Chery, and why here?

Chery is one of China’s largest automotive manufacturers, but it is often misunderstood. It is not a state-owned juggernaut parachuted into markets for political theatre. It is a commercially driven exporter with years of experience adapting vehicles for overseas customers. Through brands such as Omoda and Jaecoo, it is targeting Europe’s mainstream segments rather than the luxury end.

Chery’s problem is not engineering capability. It is access. Tariffs, shipping disruption, regulatory complexity, and political scrutiny all raise the risk of relying purely on imports. Local assembly changes that equation overnight. It reduces logistics exposure, helps navigate rules-of-origin requirements, and creates a credible story of local value creation.

In the current trade environment, that story matters.

Why this could strengthen JLR, not weaken it

For JLR, a contract manufacturing arrangement would not imply brand dilution. Properly structured, it would involve production without promotion. No shared marketing. No shared identity. Just better use of expensive assets.

The benefits are concrete. Improved utilisation lowers unit costs. Steadier volumes protect jobs and stabilise shifts. Skills are retained rather than allowed to atrophy during transition. Fixed assets begin to earn rather than drain cash.

There are operational gains too. Contract manufacturing demands rigorous process definition, traceability, and quality governance. Those disciplines sharpen internal capability rather than eroding it.

Manufacturing as economic lifeblood

This is where lived experience matters. Factories do not exist in isolation. My own plant in the 1980s survived because it sat inside a dense supply chain ecosystem. When Ford was busy, we were busy. When Black & Decker had demand, it rippled outward. Volume sustained suppliers. Suppliers sustained skills. Skills sustained towns.

When that ecosystem collapsed, communities hollowed out. Manufacturing is not just another sector. It is economic lifeblood. It circulates wages, pride, and competence in places the service economy rarely reaches properly.

Keeping plants running matters not nostalgically, but structurally.

Protectionism, without the panic

There is an unfashionable word hovering here: protectionism. Used crudely, it destroys value. Used intelligently, it reshapes incentives.

Tariffs, local content rules, and procurement frameworks increasingly reward production close to end markets. If those pressures bring companies like Chery to Britain to assemble vehicles here rather than ship them wholesale, that is not a defeat. It is how virtuous circles restart.

Assembly leads to suppliers. Suppliers lead to skills. Skills lead to resilience.

Risks, and how to manage them

There are real risks. Brand perception must be protected. Quality governance has to be watertight. Labour relations require honesty and trust. And any agreement must allow JLR to reclaim capacity as its own EV portfolio expands.

But these are design challenges, not fatal flaws. They are manageable with clarity and discipline.

An intelligent, not ideological, response

David Bailey’s contribution matters because it cuts through both nostalgia and panic. He is not arguing for decline. He is arguing for realism.

Factories are too expensive to sit idle. Skills are too valuable to mothball. Manufacturing still underpins our economy and our communities.

A JLR–Chery tie-up, handled as a focused manufacturing partnership rather than a symbolic alliance, could be a genuine win-win. Better use of assets. Reduced trade risk. Sustained industrial capability during transition.

Not a brave new world.

An intelligent one.

As a freight forwarder moving large quantities of after market auto parts from Asia to Europe I couldn’t agree with you more . Car manufacturers will either need to partner with Chinese auto makers or integrate to survive . In North America the big 3 are all teetering on the brink of survival . Now ,thanks to the orange dictator in the USA , tariffs may quicken their demise

Interesting.