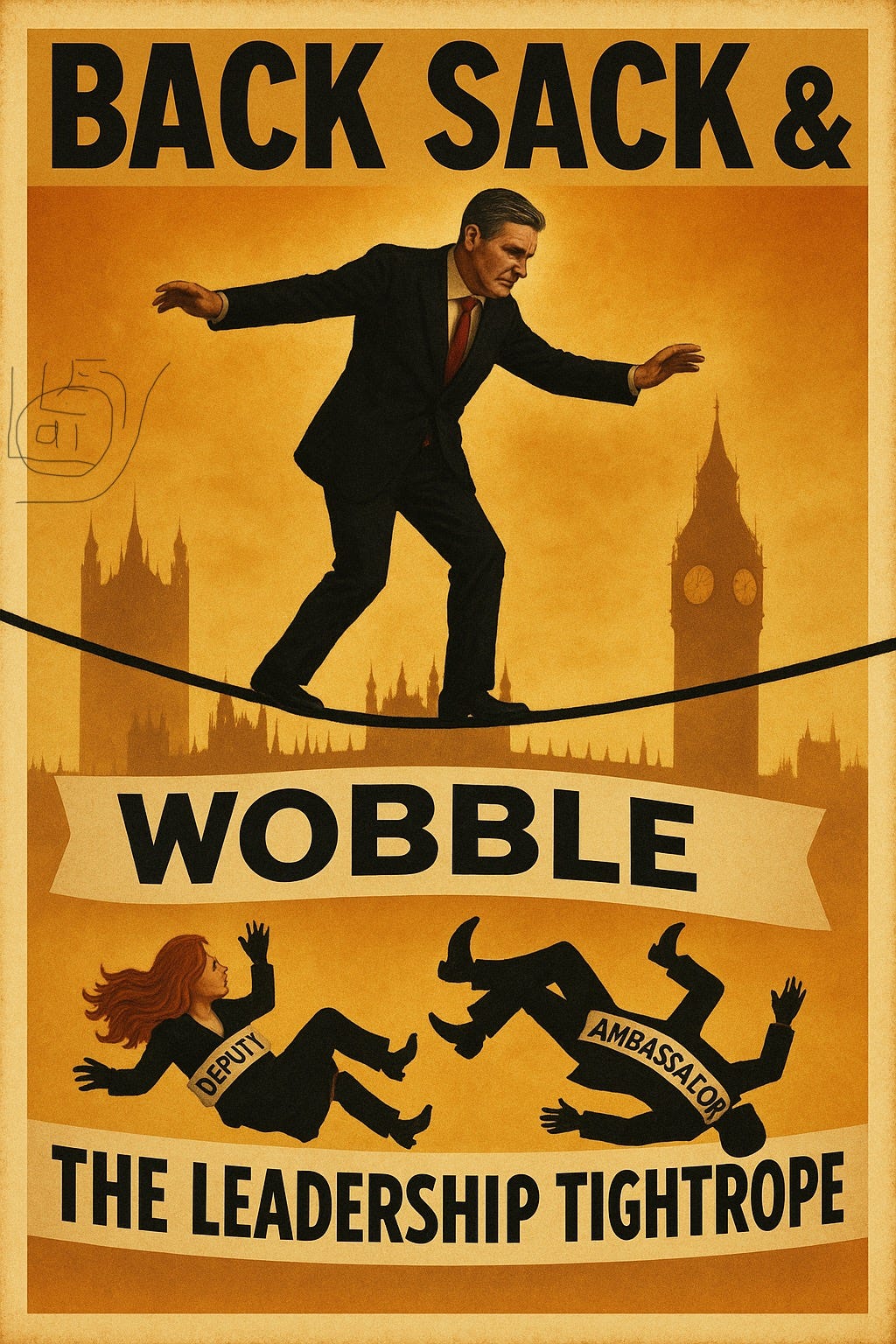

Back, Sack, .....Wobble: Starmer’s Dangerous Dance

Which brings us to Morgan McSweeney, the man behind the curtain. Starmer’s Chief of Staff....

In politics, as in life, you can tell a lot about a person by how they handle trouble. Keir Starmer has developed a routine — a little performance he repeats with unnerving precision. First, he backs them. He comes out strong, praises their integrity, insists on due process. Then, as the pressure mounts and the facts start to close in, he does the reverse. He pushes them over the side, clean and fast, as if they were never there. It’s a trick designed to look like leadership: loyal until the very end, then ruthless when required

But the act has consequences. Because each time Starmer sacrifices a colleague, it is not just the colleague who falls. He wobbles too. And the strange truth of his predicament is that the only way he finds his balance is by wobbling again, by pushing someone else out and hoping the ship steadies. It is politics as tightrope walking: dramatic, precarious, and always one gust of wind away from disaster.

Take Angela Rayner. She was his deputy, his ally, his bridge to Labour’s grassroots. When the story broke about her underpaid stamp duty — forty thousand pounds short on a Hove property arranged through a trust for her disabled son — the press smelt blood. Rayner, shrewd enough to sense what was coming, referred herself to the independent adviser. And Starmer, ever the barrister, stood at her side. He praised her openness. He said he was “proud to sit alongside her.” He framed it all as transparency.

But Rayner didn’t go immediately. She waited, she bided her time. And when the resignation finally came, it landed smack in the middle of the Reform Party’s Birmingham conference. If that was deliberate — and politics is rarely free of calculation — it certainly did the trick. Rayner’s fall dominated the headlines, left Reform’s gathering in the shadows, and ensured Labour’s crisis blotted out someone else’s message.

Then came the report. Not criminal, not corrupt, but not good enough. The adviser declared she had not met the “highest standards.” And in that instant, loyalty turned into loss. Rayner resigned her offices: Deputy Prime Minister, Deputy Leader, Housing Secretary. Starmer accepted it with solemn face and steady words. Another one gone, another problem solved. Or so he hoped.

Now look at Peter Mandelson. Old master of the dark arts, twice resigned in the Blair years, resurrected once more as Starmer’s grand appointment — Ambassador to the United States. A role meant to show gravitas, experience, continuity. Instead, it detonated in his hands. The Epstein connections, long whispered, burst into print again with venom. An email trail, a “best pal” birthday book, questions of influence and lobbying. Mandelson was toxic before his bags were even packed for Washington.

Starmer’s instinct? Support. He told journalists he had “full confidence” in Mandelson, as if confidence could cure history. Twenty-four hours later, the ground shifted again. More revelations, more fury, more headlines. And the grand statesman was gone, sacked at speed, leaving Britain without an ambassador just as the American president prepares for a royal visit.

Two examples. Two collapses. And one pattern: support first, sack second. To Starmer it looks like balance. To his opponents it looks like weakness. And to his allies it looks like danger, because once the cycle begins, someone else is always next in line.

Which brings us to Morgan McSweeney, the man behind the curtain. Starmer’s Chief of Staff, strategist, gatekeeper. The man who centralised power in No.10, cut out the left within the Labour Party, and kept Starmer’s operation running with military discipline. But also the man who vouched for Mandelson, who pushed the appointment, who waved away the risks.

Now Mandelson is gone, the Americans are irritated, and Labour MPs are restless. The President of the United States will soon be shaking hands and posing for cameras in London, and there will be no ambassador in Washington to smooth the stagecraft. Diplomats are muttering, the press are sharpening, and the knives within the Labour Party are being whetted.

McSweeney is suddenly vulnerable not because of a personal scandal, but because he is the obvious scapegoat. He is resented by the left of the Labour Party, distrusted by parts of the centre, and now blamed by many on the right who feel he has let them down. When a leader wobbles, the pack looks for someone to push, and McSweeney is the man with the target on his back.

Would his departure stabilise Starmer? Perhaps. A Chief of Staff can be moved without triggering a by-election, without tearing the Cabinet apart. Removing him would let Starmer claim: “I’ve listened, I’ve learned, I’ve changed the team.” It might buy time. It might calm the MPs. It might even reassure the Americans that someone has paid the price for the chaos.

But politics is never so simple. Rayner’s fall didn’t end the turbulence. Mandelson’s sacking didn’t restore authority. Each sacrifice buys only a little time, a brief pause before the next gust of trouble. And the polls are not moving, the press are not forgiving, and the enemies — inside and out — are circling.

There is a perversity in it all. Because we will know when McSweeney’s time is nearly up not by silence, but by noise. We will know he is reaching the end of the line when Keir Starmer begins to praise him, to insist that he has “full confidence” in him, to tell us how vital he is to the operation. That is the signal, the death knell. For in this strange dance of loyalty and ruthlessness, Starmer’s support is not a shield. It is the kiss of death.

And when that moment comes, as it surely will, the question will not just be whether McSweeney falls. It will be whether Starmer can keep his balance, or whether this time the wobble is his own.