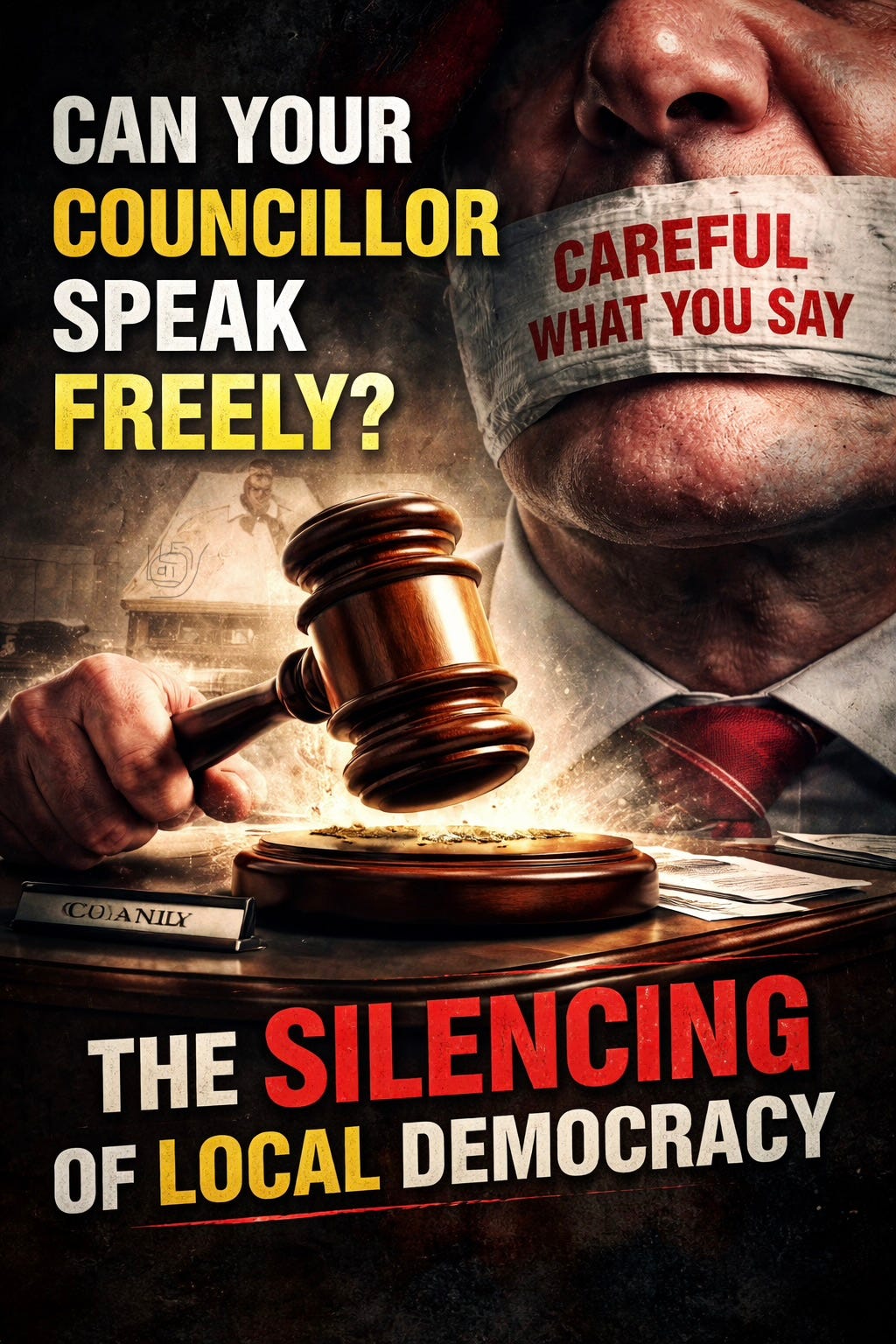

“Be careful what you say”: when legal caution quietly hollows out local democracy

When councillors speak in a properly constituted council meeting, the law affords them qualified privilege. But councillors in B'ham are told differently..!!

Anyone who has spent time in Birmingham’s Full Council chamber over the years will recognise the rhythm. The ceremonial opening, the formalities, the clearing of throats, and then, before the real business begins, a familiar warning. Councillors are reminded to be careful what they say, because they do not enjoy parliamentary privilege.

In my day, that warning was not part of the furniture. Debate could be sharp, uncomfortable and occasionally bruising. That, after all, was the point of elected representatives facing one another in public. So its regular appearance now is worth examining, not because it is wrong, but because it is incomplete in a way that matters.

The Lord Mayor, whom I have known for many years and regard as an exceptionally able and decent public servant, delivers this warning in good faith. He is plainly reading out advice placed before him. The issue is not the messenger. It is the message he has been given.

What councillors are told

The warning itself is brief and formal. Councillors are reminded that they do not have parliamentary privilege and should therefore be careful about what they say during the meeting.

As far as it goes, that is correct. Parliamentary privilege, protected by Article 9 of the Bill of Rights 1689, applies only to Parliament. MPs enjoy absolute protection. Councillors do not. No serious observer disputes that.

But the warning stops there.

What councillors are not told

What is omitted is just as important.

When councillors speak in a properly constituted council meeting, on matters of council business, they do so as elected office holders in a statutory forum. In those circumstances, the law affords them qualified privilege.

This is not a marginal interpretation. It is a long-established principle of English defamation law, recognised at common law and reflected in modern statute, including the Defamation Act. In plain terms, it means councillors are protected from defamation claims for things said in the chamber, provided they are acting within their role, honestly believe what they are saying, and are not motivated by malice.

The protection exists for a reason. Democracy requires robust, sometimes uncomfortable speech. Qualified privilege exists to make that possible.

None of this context is conveyed in the opening warning. Councillors are reminded of what they lack, but not of what the law actively protects them in doing. The result is a message that is legally accurate but materially incomplete, and one that subtly reframes the chamber as a place of personal risk rather than democratic responsibility.

The Local Government Association is very clear on this

This is not merely my interpretation. The Local Government Association’s own published guidance and training materials for councillors are explicit.

Across its Councillor Hub, induction guides for new councillors, and formal training workbooks, the LGA states that when councillors speak in council meetings they benefit from qualified privilege to allow freedom of speech. That protection applies where councillors are acting as councillors, honestly believe what they say, and are not motivated by malice.

This guidance has existed for years. It is mainstream local government advice. It is taught to councillors across England and Wales. It is not controversial.

Which makes the continued omission of this reassurance in Birmingham’s opening warning all the more striking.

This is not theoretical: the Rochdale High Court case

If anyone doubts whether qualified privilege actually works in practice, the courts have already answered that question.

In 2012, following the exposure of the Rochdale grooming scandal, the then Leader of Rochdale Council, Councillor Colin Lambert, spoke critically about private care home operators at a council-organised public forum dealing with child safeguarding. Several companies sued him personally for slander, seeking damages of £670,000.

This was not social media bravado or a careless aside. It was an elected council leader speaking in his official capacity, in a public setting, on a matter of acute public concern.

The case went to the High Court. It was dismissed.

The court accepted that the remarks were made in the course of public duty, on a matter of public interest, and were therefore protected by qualified privilege. The claim failed.

That case matters. It demonstrates that qualified privilege is not a comforting theory whispered in legal textbooks. It is a real, functioning protection that courts are willing to apply, even when the speech is controversial and the stakes are high.

If a council leader can survive High Court litigation for speaking out on safeguarding failures, it is difficult to argue that routine question time requires councillors to be pre-emptively chilled.

So why the warning persists

If the law is this clear, why does the warning continue to be framed this way?

The answer lies less in conspiracy than in culture.

Council legal teams exist to minimise institutional risk. They are corporate advisers, not constitutional guardians. Faced with nuance, they simplify. Faced with discretion, they prefer restraint. Explaining qualified privilege properly would empower councillors to exercise judgment, confidence and challenge. From a managerial perspective, that introduces unpredictability.

So the advice is pared back to its safest possible form: you do not have parliamentary privilege, be careful what you say. True, but incomplete. And incompleteness, repeated often enough, shapes behaviour.

This is not about malign intent. It is about how bureaucracies drift. Over time, risk management displaces democratic courage. Debate is softened. Scrutiny becomes performative. Power migrates quietly from the elected to the unelected.

Why the Lord Mayor is not the problem

It matters to say this plainly. The Lord Mayor is not the villain of this piece. He acts on advice. He fulfils a ceremonial and procedural role. To attack him would miss the point entirely.

The real question is why the advice placed in his hands consistently emphasises danger while omitting protection. Why councillors are told what they do not have, but not what the law and national guidance say they very clearly do have.

That omission has consequences.

What councillors should do

Councillors concerned about this framing should not rely exclusively on in-house advice from the same officers who draft the warning. That advice is necessarily shaped by corporate risk, not democratic function.

There are obvious alternatives. Labour councillors can seek independent guidance through the Association of Labour Councillors. Conservatives through the Conservative Councillors’ Association. Liberal Democrats through ALDC. Independent councillors are equally entitled to approach the Local Government Association or obtain their own specialist public law advice.

There is nothing improper about doing so. On the contrary, it is a basic safeguard when elected representatives are being subtly encouraged to temper their speech.

The uncomfortable conclusion

At this point, the position is no longer unclear. The Local Government Association is well on top of this issue. Its guidance and training materials repeatedly and explicitly recognise councillors’ qualified privilege in meetings, precisely to allow freedom of speech.

Against that background, the continued presentation of a one-sided warning at Birmingham’s Full Council meetings looks less like legal necessity and more like selective caution. Councillors are reminded of what they lack, but not of what the law actively protects them in doing.

This is not about catching anyone out. It is about recognising a pattern. Legal advice that is technically correct but selectively framed has consequences. Over time, it dulls debate, flattens scrutiny and subtly reshapes who really feels confident to speak.

And if any of the council’s legal officers would like further information on the subject, I am very happy to point them towards the relevant statutory framework, or indeed the Local Government Association’s own guidance and training workbooks. They already know where to find it. I can always resend the links.

Local democracy does not need to be wrapped in bubble wrap. It needs clarity, confidence and the courage to say uncomfortable things, safe in the knowledge that the law was designed to protect exactly that.

The law is not the problem. The way it is being selectively explained might be.