Carl Chinn and the Difference Between Myth and Meaning

The Peaky Blinders gave Birmingham global recognition, but Carl Chinn gives it something better. Context, honesty and a moral backbone rooted in working class experience, not myth making.

I am enjoying a properly restful break over Christmas, the rare kind where the noise drops away and time stretches just enough to let your thoughts settle. And what better moment than that to dip into a book. Not something skimmed between emails or half read before sleep, but something you can return to slowly, chapter by chapter, with no urgency pressing in.

And who better to read in that frame of mind than one of the grandees of our region. Carl Chinn has become almost a prophet in our town. A familiar voice, a trusted guide, someone who has spent decades explaining Birmingham to itself with patience, precision and respect. There is a parallel universe where Carl Chinn stood for Birmingham Mayor and pulled it off with ease, calmly outclassing the noise and the slogans. He has that rare combination of authority and warmth that people instinctively trust.

Back to terra firma.

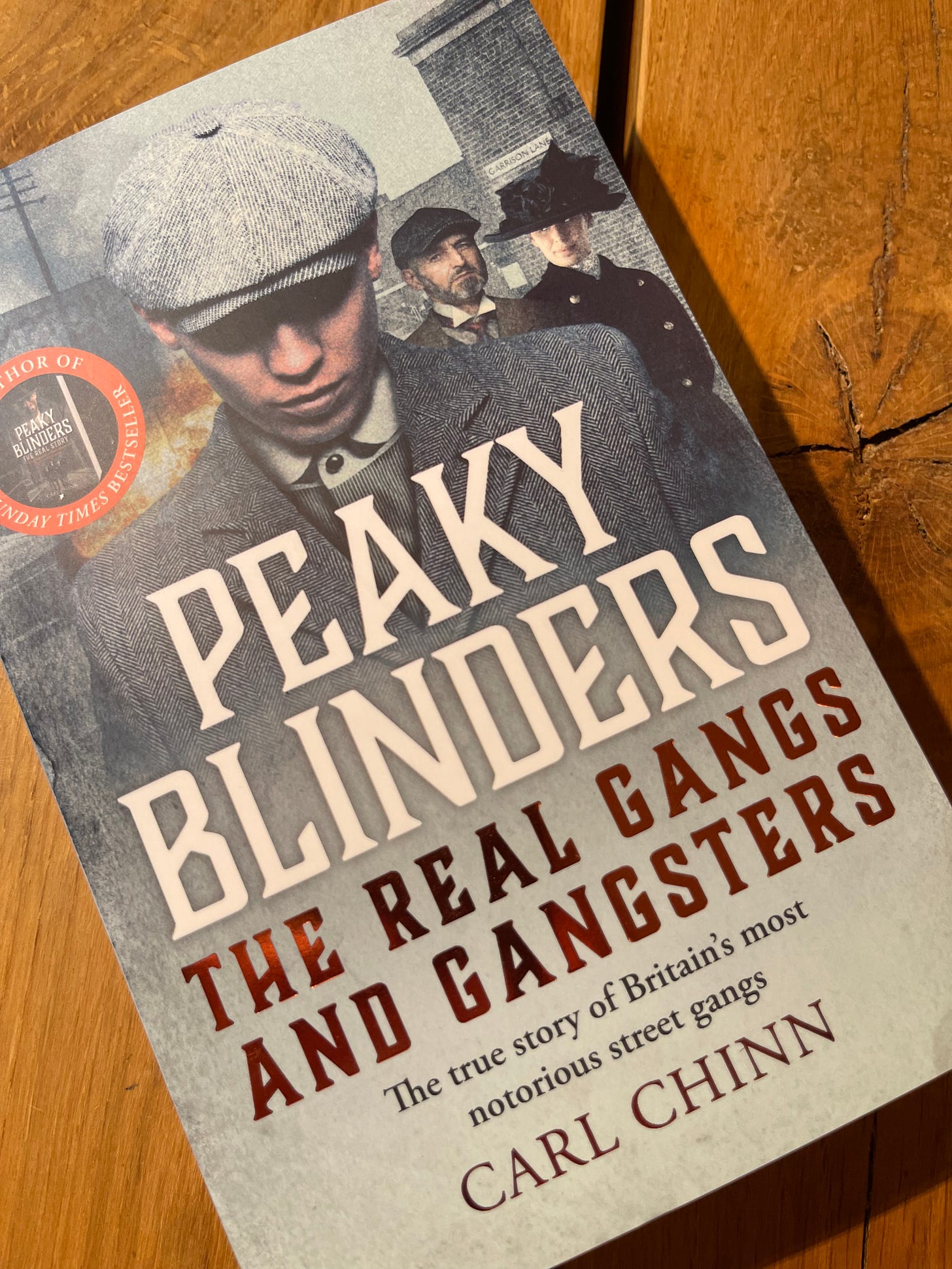

The book in question is The Real Peaky Blinders, and it is exactly what its title promises, and more besides. This is not a television tie in, nor a glossy companion to stylised violence and flat caps. It is a serious, grounded work of social history that restores Birmingham’s gang culture to its proper context, stripped of myth and returned to lived reality.

This is one you need to buy, whether you are building a serious reference shelf for yourself or picking it up for anyone with a genuine interest in the history of Birmingham or the reality behind the Peaky Blinders legend. It treats the city with seriousness and intelligence, and it assumes the same of its reader.

Carl Chinn has a rare ability to make the past feel close without turning it into folklore. His style is authentic, grounded and quietly authoritative. He does not shout for attention or lean on gimmicks. He does not need to. Page after page, he holds you through detail, context and an instinctive understanding of how Birmingham actually worked at street level.

One of Chinn’s great strengths is his refusal to romanticise. He understands why myths form and why certain stories harden into legend, but he is far more interested in what really happened and why. His Birmingham is not a stage set for swagger and slow motion drama. It is a dense industrial city shaped by work, proximity, poverty and ambition. Crime, when it appears, is not glamourised. It is explained, situated and stripped of theatrical varnish.

For readers whose first encounter with the Peaky Blinders came via television, this distinction matters. The series trades heavily in stylisation and mood. Chinn calmly removes that filter. He replaces it with streets, families, workplaces and consequences. You begin to see how reputation functioned, how gangs emerged not from romance but from circumstance, and how survival often demanded choices that carried long shadows.

Peaky Blinders inevitably sits in the background of any modern discussion of Birmingham gangs, but Chinn never allows it to dominate. Instead, he patiently reclaims the subject from fiction and returns it to history. What emerges is more complex and, in many ways, more unsettling. These were not anti heroes performing for an audience. They were men shaped by limited options, operating in a city that offered few clean exits.

What makes the book particularly strong is its balance. It is accessible without being simplistic, detailed without becoming heavy. Chinn introduces context without breaking the rhythm of the narrative. You are never lectured. You are guided. Dates, names and places are woven in naturally, almost conversationally, but always with precision. It is the work of someone who knows his material so well that he does not need to prove it.

There is also a deep respect running through the book. Respect for the city, for its working class history, and for the reader. Chinn does not assume ignorance, nor does he posture. He trusts the reader to keep up, and that trust is repaid. You find yourself slowing down, not because the book is difficult, but because it is rich.

I should say at this point that I have not quite finished it yet. Christmas has been a blessing in that regard. I am now at that familiar stage with a good book where I deliberately ease my pace. I read a chapter, then stop. Not because my interest is fading, but because I do not want it to end too quickly. I can get like this when a writer has earned my attention and kept it without tricks.

That reaction feels telling. This is not a book you rush through for plot. It is one you inhabit for a while. You find yourself thinking about it away from the page. About how cities remember and forget. About how stories are simplified, then sold back to us. About how Birmingham, in particular, has so often been caricatured or spoken for by people who never really listened.

Chinn pushes firmly against that. He writes Birmingham as a place with agency. A city that shaped behaviour as much as it was shaped by it. Industrial rhythms, housing patterns and informal economies are treated not as background colour, but as active forces. You come away with a sharper sense of why things happened where they did, and why certain patterns repeated.

There is something quietly political in this approach, although Chinn never waves a banner. By insisting on accuracy and context, he resists the flattening of working class history into entertainment. He reminds us that behind every legend are real people who lived with the outcomes of their choices, and often paid heavily for them. That insistence feels particularly important now, when history is so easily repackaged and stripped of consequence.

For Brummies, the book carries an extra resonance. Streets you recognise. Districts that still hum with memory. Names that echo through family stories and local lore. But it never collapses into nostalgia. Chinn understands that affection for a place does not require sentimentality. In fact, he is at his best when Birmingham is allowed to be complicated, contradictory and occasionally uncomfortable.

For readers beyond the city, the book works just as well. It offers a grounded insight into how industrial Britain functioned at street level. How informal power structures developed. How communities policed themselves when official systems were absent or indifferent. In that sense, it speaks far beyond Birmingham alone.

By the later chapters, you realise that Chinn is offering more than a correction of myth. He is giving the reader a way of seeing. You begin to question other stories, other cities, other legends. That is the mark of serious historical writing, even when it wears its scholarship lightly.

In short, whether you are a Brummie, a social history enthusiast, or simply curious about what really sat beneath the flat caps and bravado, this book rewards your time. It will keep you reading, and more importantly, thinking.

There is also a moral distinction here that deserves to be stated plainly. The Peaky Blinders may have given Birmingham a certain global resonance, but it is a hollow one. They were not folk heroes. They were violent, predatory men who thrived on fear, intimidation and the misery of others. Strip away the stylisation and they are not something the city needed, admired, or should romanticise. We would have been just fine without them.

Carl Chinn, on the other hand, represents the very best of Birmingham. An intellectual in the fullest sense of the word, but one who has never betrayed his working class roots. He did not climb out and then pull the ladder up behind him. He did not confuse education with entitlement, or comfort with superiority. Too many who escape poverty decide that distance makes them better than those still living with less. Chinn never does. His scholarship carries loyalty, memory and respect, and it shows on every page.

Where criminals took from the city, he gives back to it. Through truth rather than myth. Through clarity rather than noise. Through a deep, steady commitment to telling Birmingham’s story properly, without varnish and without shame. Chinny is not a legend manufactured for export. He is the real thing. A Brummie treasure.

It is absolutely worth buying this book. As a post Christmas present, it is hard to beat. And if you are buying it for yourself, make space on the shelf. This is one you will want to return to.