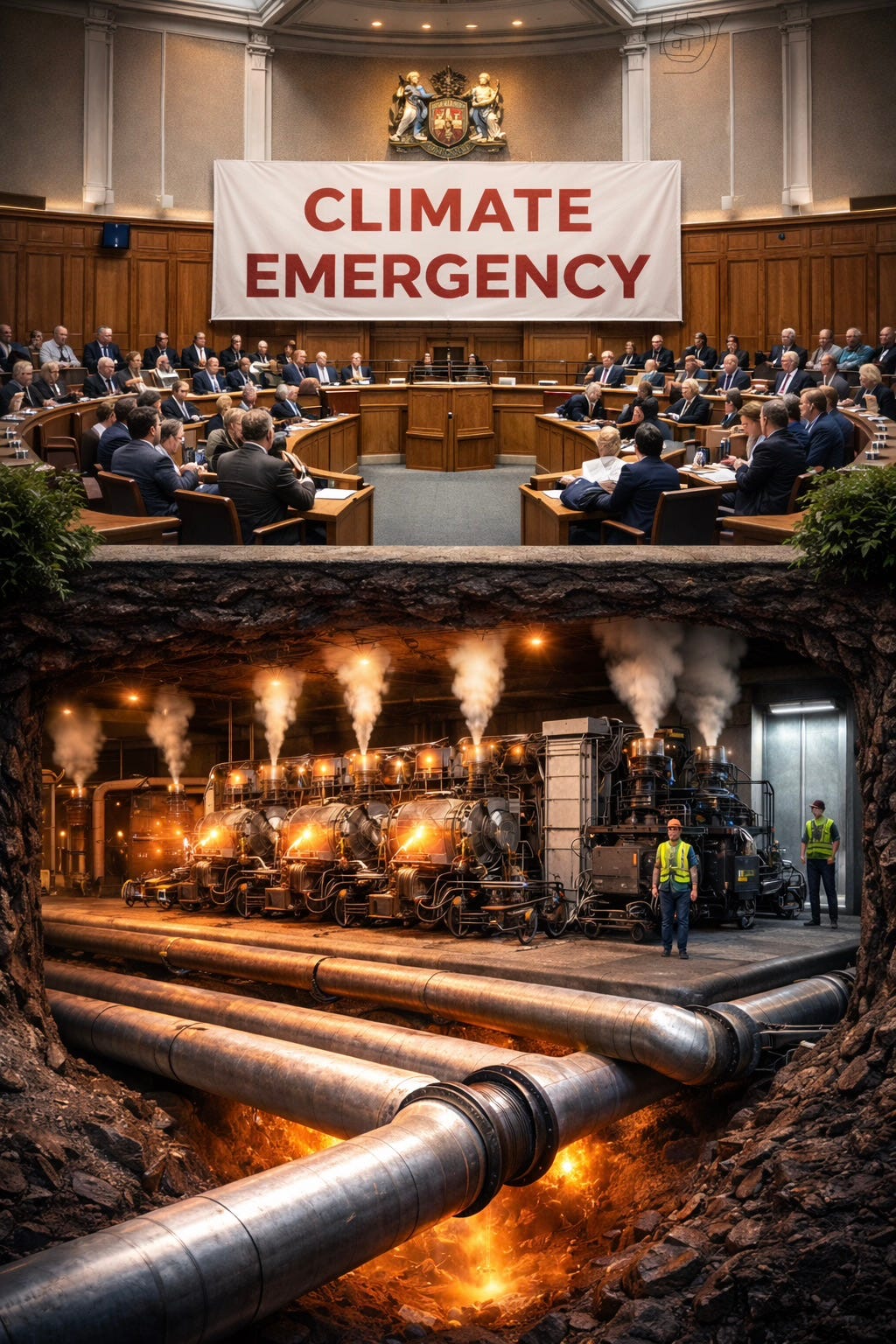

Climate Emergency? Then Act Like It.

Birmingham declared a climate emergency. Beneath Broad Street, gas engines kept humming. If it’s an emergency, upgrade the plant.

In 2019 Birmingham City Council declared a climate emergency. It required a motion, a vote and a press release. What it did not require was touching the pipes beneath Broad Street. Beneath the city centre runs the Birmingham District Energy Company network, a central heating system that delivers more than 60 million kilowatt hours of heat each year through over twelve kilometres of buried insulated pipework. The council declared an emergency. The pipes kept working exactly as they had the day before.

Emergency is a word. Engineering is a commitment.

The Birmingham District Energy Company network is not symbolic. It is real infrastructure. Instead of thousands of separate buildings each running their own boiler, heat is generated centrally at a handful of energy centres and pumped as hot water through pipes to major sites including the International Convention Centre, Aston University, Birmingham Children’s Hospital and residential towers.

According to the council’s own Birmingham City Centre Network Decarbonisation Roadmap Stage 3 Executive Summary, the system supplies around 60.6 million kilowatt hours of heat annually. That is roughly enough to warm five to six thousand average British homes each year. Peak demand exceeds 16,000 kilowatts. The energy centres also generate over 38 million kilowatt hours of electricity using gas-fired combined heat and power engines.

This is serious civic infrastructure.

When much of this plant was installed between 2007 and 2018, it was regarded as progressive. Combined heat and power, which burns natural gas to generate electricity and captures the waste heat, was more efficient than thousands of individual boilers and distant power stations. In its day, it reduced duplication and improved fuel use. By the standards of the time, it was green.

But green is not a badge. It is a metric.

The council’s own roadmap acknowledges that as the national electricity grid becomes cleaner through wind and solar generation, the carbon advantage of gas-fired combined heat and power shrinks. As grid electricity decarbonises, continuing to burn gas locally looks less impressive in carbon terms.

It was green then. It is not green enough now.

That does not make the network a mistake. It makes it unfinished.

Before anyone rushes to tear it down in the name of purity, it is worth asking what actually counts as green. If green means replacing thousands of inefficient boilers with a shared heating backbone, Birmingham has already made a structural environmental gain. Fewer boilers mean less duplication of materials, fewer flues, fewer replacements and higher operational efficiency. A centralised system can be maintained professionally and optimised properly.

That is not virtue signalling. That is engineering.

The advantage of a district heating network is not the fuel it starts with. It is its ability to change.

The Decarbonisation Roadmap explores options including large electric heat pumps. Electric heat pumps use electricity to move heat from air or water into the network. As the national grid becomes cleaner, electric heat becomes cleaner automatically. The report also identifies the importance of lowering what engineers call return temperatures.

Return temperature is simply the temperature of the water coming back from buildings to the energy centre after it has delivered heat. The lower that return temperature, the more efficient the system becomes. High return temperatures mean buildings are not using heat efficiently. Lowering them improves performance and makes electric heat pumps viable at scale.

This is not glamorous work. It involves controls, radiators and system optimisation. But it is where real decarbonisation lives.

If you are serious about being green, you do not need theatrics.

You need carbon intensity per kilowatt hour delivered falling year after year. You need return temperatures coming down. You need a timetable for phasing out routine gas combustion. You need investment in plant upgrades.

Birmingham already has the backbone. Twelve kilometres of insulated pipework bind the city centre into a shared thermal system. That is something to build on, not apologise for.

So here is the bold question.

If we have declared a climate emergency, why are we not expanding this backbone?

Thousands of suburban homes across Birmingham each run their own boiler. Each has its own flue, its own replacement cycle, its own inefficiencies. If district heating is structurally more efficient, if it reduces duplication and allows fuel switching at scale, then why is the ambition limited to the city centre?

Why not roll it out gradually into high-density suburban areas? Why not design new developments around connection from day one? Why not retrofit and electrify the existing network properly and then extend it?

If emergency language is to mean anything, it should mean scale.

New York’s steam system survived for more than a century because the architecture endured and the fuel evolved. Birmingham has built a modern version of that architecture. The pipes are there. The plant is there. The report is written.

What is missing is momentum.

Less performance. More pipework.

Less congratulating ourselves for passing motions. More publishing decommissioning schedules.

Birmingham does not need another declaration. It needs to finish what it has already started beneath its own streets.

If this is truly a climate emergency, then treat the district heating network as strategic infrastructure. Retrofit it. Electrify it. Expand it.

Make it future-proof.