Crossing the Line: What Happens When Protest Tips into Support for Terrorists

Hint: it’s not just UK law you need to worry about - US border agents are watching too.

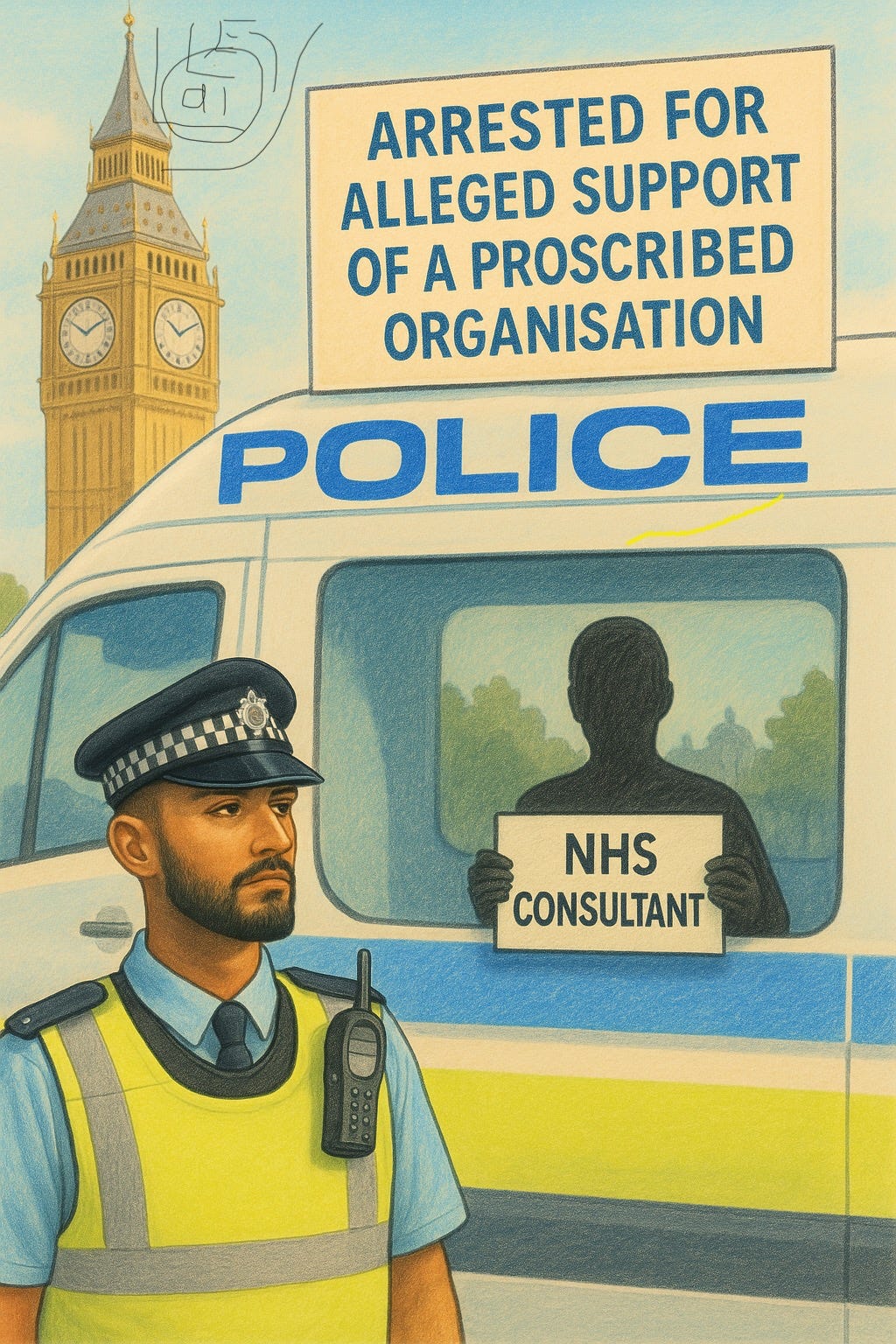

A striking image circulated recently: a senior NHS consultant sitting in the back of a police van, clutching a handwritten sign identifying his profession, while a police officer of immigrant heritage stood guard outside. Big Ben loomed in the background, as if to remind us of the authority of the state and the weight of history.

For some, this was a snapshot of Britain’s supposed decline: the state silencing dissent, criminalising doctors, and proving once again that colonialism never truly left, it merely changed uniforms. The caption accompanying the photograph made exactly that case, lamenting that the country shields genocide while punishing those who demand justice.

But there is another reading of this same image, one which speaks not to state repression but to the dangerous naïvety of privilege. The missing detail in the consultant’s placard was not his job title but the cause he had chosen to align himself with: support for Palestine Action, now a proscribed terrorist organisation in the United Kingdom.

And that makes all the difference.

⸻

Protest, Privilege, and Peril

It is easy for comfortable professionals to treat protest as a kind of theatre. They imagine that standing in front of Parliament with a piece of cardboard is little more than an expression of conscience, a temporary vent of middle-class outrage. They believe their job title and social standing shield them from real consequences.

But the law in this country is crystal clear. Once the government designates an organisation as proscribed under the Terrorism Act 2000, supporting it — financially, materially, or symbolically — is a criminal offence. Palestine Action is on that list. To promote or encourage support for it, even indirectly, is to step into the realm of terrorism.

This is not a matter of interpretation, ideology, or political spin. It is statutory fact.

⸻

Arrest vs Charge — and the Files That Remain

It is worth noting, of course, that being arrested does not automatically lead to being charged. The police may detain individuals, question them, gather evidence, and ultimately decide there is insufficient ground for prosecution. But even if no charges follow, the stain of arrest lingers.

What many people do not realise is that arrests leave a paper trail. There is something known in policing as “Chief Constable’s Knowledge.” In plain terms, this means that even if charges are dropped, or never pursued, the fact of your arrest is recorded and stored on police systems. It may not appear on a standard criminal record check, but it sits in intelligence files. It can resurface in enhanced vetting, in security clearance applications, and sometimes in sensitive professional contexts.

So the NHS consultant, even if released without charge, is not walking away untouched. That file will exist. It will note that they were arrested in relation to support for a proscribed terrorist organisation. It is naïve to think that such a record is meaningless. For professionals whose careers depend on trust, integrity, and mobility, it can be devastating.

⸻

Travel Bans and Global Consequences

Beyond the UK, there are immediate international implications. The United States operates one of the most stringent visa systems in the world. Any hint of terrorism-related activity — arrest, charge, or even association — can lead to exclusion.

And it is not just America.

• Canada maintains tough security screening for anyone linked with extremist or terrorist activity. A simple arrest can be enough to trigger a refusal of entry.

• Australia applies strict character tests for visas; involvement with terrorism, even without conviction, can bar travel or residency.

• New Zealand mirrors this approach, sharing intelligence with its allies under the “Five Eyes” network. An arrest for supporting a proscribed group in the UK will not go unnoticed.

• Japan enforces uncompromising entry restrictions for those with criminal or terrorism-related associations, often erring on the side of caution.

• Singapore has a reputation for zero tolerance: its Internal Security Act allows authorities to deny entry to anyone suspected of terrorist sympathies.

• South Africa has in recent years toughened its stance, refusing visas to individuals linked with extremist organisations, citing the need to protect its own security.

For many professionals, these are not distant concerns. The consultant in question may have children studying abroad, colleagues working overseas, or opportunities to attend international conferences. Overnight, entire continents can become off-limits. A lifetime of mobility and professional exchange is jeopardised because of a single act of reckless protest.

⸻

Professional Consequences

Within the NHS, the stakes are equally high. Patients must trust their doctors. Staff must uphold not only clinical standards but also public confidence. A doctor whose name is linked with terrorist support cannot escape questions about judgement, impartiality, and reliability.

Regulatory bodies like the General Medical Council are bound to consider such matters. Employers will weigh reputational risk. Colleagues will question loyalties. The principle of “do no harm” does not sit easily with visible support for an organisation that the state has judged as a threat to national security.

This is not to say that doctors, or any professionals, should be stripped of their right to protest. But when protest crosses into explicit support for proscribed organisations, it ceases to be a matter of conscience and becomes a matter of law. And the law is unforgiving.

⸻

The Disconnect

What is most striking about the consultant-in-the-van image is the disconnect between perception and reality. Those who hailed it as evidence of repression framed it in terms of “lived experience” — the noble dissenter silenced by the machinery of the state. But this is a selective lived experience, one insulated by class and privilege.

For many others in Britain — those from immigrant backgrounds, working-class communities, or groups already subject to close surveillance — the idea of openly supporting a proscribed organisation would be unthinkable. They know the consequences. They live with them daily. They understand that the law is not a theatre but a set of rules that can and will be enforced.

It is precisely this gulf — between those who treat protest as a symbolic gesture and those who live with the constant threat of its consequences — that makes the consultant’s actions appear so reckless.

⸻

The Broader Point

None of this diminishes the legitimate grief and anger over Gaza, nor the right of citizens to protest UK foreign policy. Those are essential democratic freedoms. But the line is drawn, firmly and clearly, at support for proscribed groups.

To ignore that line is not an act of heroism but an act of folly. It risks careers, reputations, and freedoms. It hands the state every justification it needs to intervene. And it undermines the very causes it claims to advance by blurring legitimate protest with unlawful extremism.

⸻

Conclusion

The image of an NHS consultant in a police van may strike some as a symbol of state repression. But it should also serve as a warning: titles and salaries do not place one above the law. To support a proscribed terrorist organisation, however indirectly, is to invite consequences that extend far beyond a night in the cells.

From the permanent shadow of “Chief Constable’s Knowledge” files, to travel bans spanning the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Singapore, South Africa and beyond, the risks are global. From professional ruin to reputational collapse, the consequences are profound.

Middle-class protest culture may treat cardboard placards as harmless props. The law does not.

In Britain today, one cannot be both a respected professional and a supporter of terrorism. The sooner this reality is recognised, the fewer careers, reputations, and futures will be needlessly destroyed.