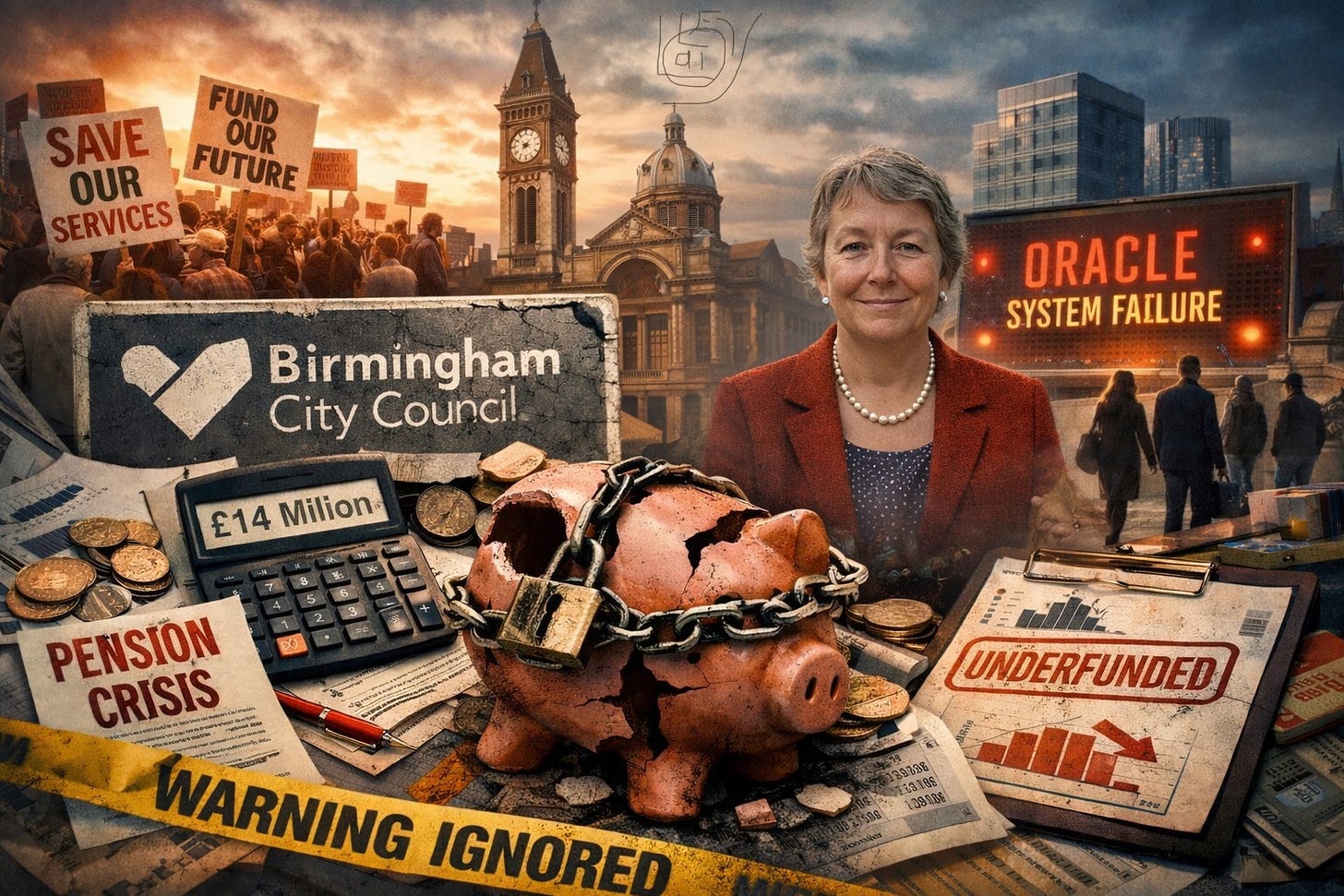

Everyone Was Warned. Birmingham Is Still Paying. And the Reckoning Is Now Inevitable.

Several million more still being paid by the end of the year, for no identified purpose at all.

Birmingham City Council is still paying around £14 million a year in pension deficit reduction contributions for a deficit it now acknowledges does not exist. Those payments have continued even after the council recognised that the West Midlands Pension Fund is in significant surplus. This is the central point of the latest analysis by Professors John Clancy and David Bailey, and it is not a technical curiosity. It is a live failure of financial governance, still draining money from public services while those responsible appear unwilling to explain why it is happening.

Clancy and Bailey’s latest blog matters precisely because it does not introduce a new argument. It removes the last remaining excuses. The numbers are no longer contested. The surplus is acknowledged. And yet the payments continue.

They set the position out plainly. Birmingham City Council has continued to pay a deficit reduction contribution equivalent to around 5.2 per cent of payroll, amounting to roughly £14 million a year, even after formally recognising in October 2025 that there was no deficit to reduce. With seven months of the financial year still to run at that point, the council carried on paying regardless. By Clancy and Bailey’s arithmetic, this meant around £8.2 million committed after the admission, and several million more still being paid by the end of the year, for no identified purpose at all.

This is not an accounting quirk. It is not a rounding error. It is a prolonged collapse of judgement with a monthly payroll attached.

To understand why this matters, it helps to be clear about the basics. The Local Government Pension Scheme (LGPS) is the pension scheme for council staff and many other public sector workers, including education staff, firefighters and police employees. Employees pay fixed contributions. Employers do not. Employer contributions are supposed to rise when a fund is in deficit and fall when it is in surplus. That flexibility is the point. When a deficit disappears, deficit reduction payments are supposed to stop or be recertified.

Clancy and Bailey argue that this did not happen in Birmingham, and that it should have.

They place the £14 million problem in a wider context. For years, pension funds including the West Midlands have relied on overly pessimistic assumptions about long-term investment returns. Those assumptions made funds look weaker than they really were, justified higher employer contributions, and reinforced a narrative of permanent scarcity that fed directly into council budgets and service cuts.

The warning signs were not hidden. They were public. This is where Isio comes in. Isio is a UK pensions and benefits consultancy that advises pension funds, employers and trustees on funding, risk and long-term sustainability. It publishes the LGPS Low Risk Funding Index, which tracks how well funded local government pension schemes are across England and Wales using deliberately cautious assumptions. The point of the index is simple. It asks whether pension funds would still be secure even if future investment returns were modest. When Isio reported LGPS funding at around 112 per cent, it was not signalling optimism but the opposite, that schemes were comfortably funded even on low-risk assumptions, and that continued high employer contributions risked unnecessary overfunding.

Clancy and Bailey are clear that this is not just a West Midlands problem. Many LGPS funds across the country are in a similar position, sitting on large surpluses while continuing to extract unnecessarily high contributions from employers who are simultaneously cutting services and pleading poverty. Birmingham is simply the clearest example of what happens when nobody acts.

The failure here is layered. First, the assumptions were wrong. Second, repeated public warnings were ignored. Third, once the scale of the surplus became unavoidable, the position was still not communicated clearly or acted upon. A distorted picture of financial reality was allowed to persist, and that picture was then used to justify years of cuts that reshaped the city.

This is not an isolated lapse. It fits a broader pattern of how risk is handled in Birmingham. The city is still living with the consequences of the Oracle IT failure, a complex system introduced with assurances, warnings downplayed, and problems treated as operational detail until they became unavoidable. The cabinet member responsible for finance, Councillor Karen McCarthy, knows what a systems failure looks like when it is not confronted early, because the city is still paying the price of that one. Which is why continued inaction on pensions matters. When an authority that has already lived through one catastrophic failure is presented with clear, public warnings about another and chooses not to act, silence stops looking like caution and starts looking like habit.

So what now?

Not appeals to conscience. That ship sailed years ago. Not another round of “lessons learned”, the language of institutions hoping delay will do their work for them. What happens next is political, because the numbers are settled and the excuses are exhausted.

The polls are clear. Reform is on course to take control of large parts of the West Midlands in May 2026. This is not speculative. It is the trajectory. Richard Tice, Reform’s Deputy Leader and a widely discussed choice for Chancellor should the party take power nationally, has already framed failures like this as proof of establishment mismanagement and as an opportunity to ease pressure on ratepayers and public bodies. That makes continued silence dangerous. This is not an endorsement. I am not a Reform supporter, and I remain a Labour Party member despite Labour’s profound lack of moral courage on this issue. It is simply a statement of political reality. When accountability is avoided for long enough, it is eventually imposed by people you would rather not empower.

It is not only Reform that senior officials should be watching. Labour itself has shown a growing willingness to drift towards Reform-style positions when polling pressure bites, most visibly on immigration. It would be naïve to assume that public sector accountability is immune from the same logic. Faced with electoral collapse, it is not impossible that Labour could seek a sudden conversion to toughness, sacrificing senior officials to demonstrate seriousness about public money. Unlikely, perhaps. Foolish to rule out.

Which brings us to the people who can no longer plausibly claim detachment. Chief executives. Chief finance officers. Pension fund officers. Head teachers and academy trust leaders. College principals. Police and crime commissioners. Fire authority chairs and senior governors. These are not spectators. They are the custodians of public money and public trust. Their institutions were told there was no alternative to cuts, closures and retrenchment while contribution decisions continued to be shaped by assumptions that were increasingly detached from reality.

Education leaders understand long-term planning and actuarial logic. Fire authority leaders deal in risk, prevention and preparedness as a matter of daily practice. Yet when faced with repeated, public warnings about pension assumptions and their consequences, too many deferred, stayed agreeable, and waited for someone else to act.

This is how collective negligence works. Not through malice, but through diffusion. Everyone assumes someone else will intervene. Everyone waits. And in the end, nobody does.

I wrote to the cabinet member responsible for finance to ask a straightforward question: why deficit reduction payments continue despite the acknowledged absence of a deficit. No response was received by the deadline offered.

The wider lesson is uncomfortable. Local government has become adept at mistaking process for intelligence and hierarchy for wisdom. Ideas are taken seriously not because they are correct, but because of where they come from. Independent voices are tolerated briefly, then sidelined. Challenge is managed. Assumptions harden into dogma. Groupthink is mistaken for stability.

Even now, the instinct is to soften rather than confront. To manage perception rather than accept responsibility. To hope that time, complexity and distraction will dull the edge.

They will not.

For decades, the quiet bargain of public administration has been simple. When things go wrong, politicians take the heat, reports are written, and senior officers retire on schedule. Careers end politely. Pensions remain intact. Accountability is managerial, never personal.

That assumption is now unsafe.

If Reform does translate its polling into national power, it is entirely plausible that this culture of insulation will be reframed as evidence of elite impunity. The pension fund story fits that narrative perfectly. It requires no conspiracy, no corruption, only indifference and the appearance that those responsible faced no personal consequence while services were stripped and money was quietly hoarded.

In that climate, legislation aimed at senior public servants would not be fringe. Pension reform for top officials, clawback provisions, limits on indemnities, mandatory public accountability hearings, restrictions on post-retirement benefits, all would be politically viable and likely popular. Whether such measures would be just or proportionate is almost beside the point.

This is the real cost of silence. Accountability deferred does not disappear. It changes hands.

Clancy and Bailey did their job. They spoke up. They explained. They persisted. They refused to let institutional discomfort override arithmetic.

The failure belongs to those who had the power to act and chose not to listen. And until this region learns to value inconvenient clarity over comfortable authority, it will keep repeating the same mistake. Different numbers. Different reports. Same consequences.