FOLLOW THE MONEY

How Birmingham Stopped Building — and Watched the Market Take Over

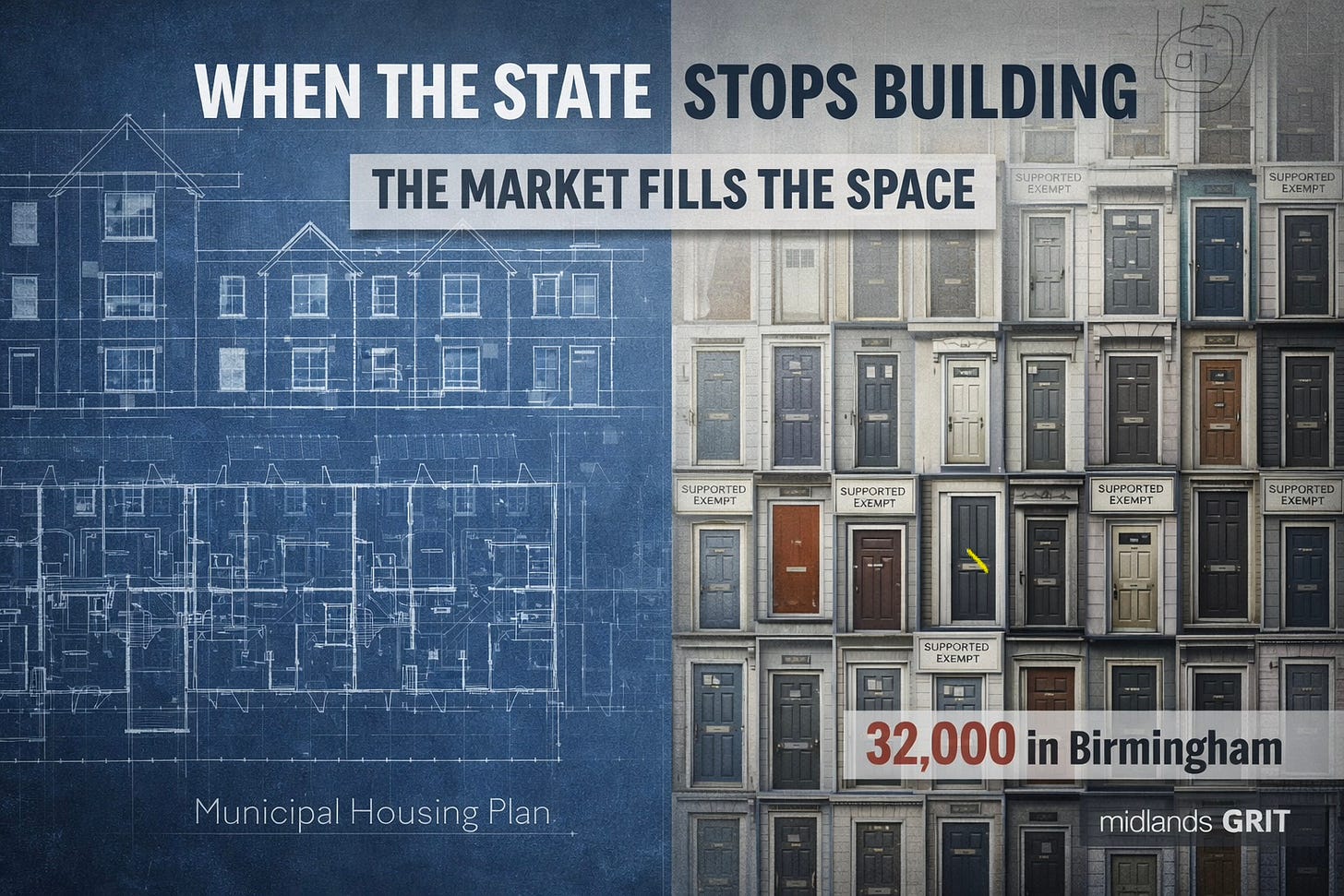

There are more than 32,000 people living in supported exempt accommodation in Birmingham.

That is not a marginal statistic. It is not a footnote in a policy document. It is the equivalent of a town the size of Sutton Coldfield housed under a classification most residents had barely heard of ten years ago.

Now place another fact beside it.

In March 2025, Birmingham City Council formally wound up its own housebuilding arm, Birmingham Municipal Housing Trust.

One system expanding.

One system retreating.

If you want to understand what has happened to housing in Birmingham, start there.

A City Within the City

Walk through parts of Erdington, Handsworth, Ladywood or Hall Green and the change is visible.

Former family homes converted into multi-occupancy properties.

Short-term placements.

Support workers arriving at irregular hours.

Neighbours unsure who lives next door from one season to the next.

Supported exempt accommodation was created with good intentions. It was meant to provide housing with structured support for people leaving prison, escaping abuse, struggling with addiction or managing serious mental health issues.

The higher rent is justified because support is meant to be built into the model.

But policy intention and economic incentive are not the same thing.

When a property can command higher housing benefit because it carries an “exempt” classification, and when oversight is uneven, a market will grow into that gap. Investors notice. Operators expand. The system scales up faster than enforcement.

That is not ideology. It is arithmetic.

Why Birmingham?

Birmingham did not consciously decide to become a focal point for supported exempt accommodation. It drifted there through a mixture of demand and permissiveness.

Large volumes of older housing stock suitable for conversion.

High homelessness demand.

A benefits structure that pays more for exempt status.

A regulatory framework that struggled to keep pace.

Under the current administration, the sector expanded rapidly. Whether through drift, stretched capacity or deliberate caution, the environment allowed growth to outstrip oversight.

Councillor Lee Marsham has repeatedly warned that rogue operators are exploiting vulnerable tenants and communities. He has urged colleagues to “follow the money”. That phrase has resonated because it captures a growing sense that financial incentive is driving too much of the expansion.

And then there is the politics of proximity.

Property interests are not abstract in Birmingham. It is widely known that some councillors, or their close relatives, have been connected to HMO or supported accommodation properties. That fact alone does not imply wrongdoing. But in a city wrestling with saturation and concentration, it inevitably sharpens the debate about transparency and perception.

At recent meetings, some councillors have felt the need to state publicly that they do not run HMOs, or the like.

That tells you how politically charged the subject has become.

The Municipal Retreat

For more than a decade, Birmingham Municipal Housing Trust represented something different. It was the council building again. Thousands of homes delivered. A visible statement that the city would shape its own housing future.

Then came financial crisis.

The Section 114 notice in 2023. Equal pay liabilities running into hundreds of millions. Commissioner oversight. A pivot toward compliance and immediate risk reduction.

In February 2025, the future of BMHT was reviewed.

In March 2025, it was wound up.

The official explanation was rational. Capital needed to be redirected to fix existing stock. Safety and decency standards came first. Acquisitions were quicker than new builds. Financial caution was unavoidable.

All of that is true.

But it is not the whole story.

The Finance Question

A council house is not simply expenditure. It is a long-term income-generating asset.

Rental income flows for decades. The Housing Revenue Account is ringfenced. Borrowing for housing sits differently from general fund liabilities. Other councils under financial strain have still structured joint ventures and development partnerships to keep building.

Financial crisis explains caution.

It does not automatically explain the absence of ambition.

Birmingham chose to stabilise and consolidate. It did not choose to replace its direct building arm with an equally bold alternative vehicle.

That choice may have been understandable in the short term.

But it had structural consequences.

When the State Steps Back

While the council retrenched, supported exempt accommodation continued to expand.

Private operators moved quickly. Demand was immediate. Incentives were clear. Oversight lagged behind.

This is not a story of conspiracy.

It is a story of sequencing.

Municipal contraction.

Market acceleration.

Regulation following behind.

When the state retreats from direct provision, the market fills the vacuum. That is not a moral judgement. It is a pattern seen repeatedly in housing policy.

The Supported Housing Regulatory Oversight Act promises tighter standards. But legislation does not rebalance a market overnight.

Meanwhile, communities live with the results.

Compliance Through Inertia

Birmingham today is not in housing collapse.

It is not in bold expansion either.

It is in compliance mode.

Roofs repaired.

Safety programmes prioritised.

Balance sheets stabilised.

But ambition narrowed.

The city that once built at scale now acquires and consolidates. The language of growth has been replaced by the language of control.

That may have been necessary in the immediate aftermath of financial crisis.

The question is whether it has become a posture.

The Question That Lingers

If Birmingham can house more than 32,000 people in supported exempt accommodation, why can it not build council homes at scale again?

If financial crisis constrained ambition in 2023 and 2024, what constrains it now?

These are not accusations. They are governance questions.

Housing shapes everything. Streets. Schools. Public health. Policing demand. Community stability. When housing policy drifts, the consequences ripple outward.

One of the councillors who has most persistently raised these questions, Lee Marsham, will step down at the May 2026 election. He has been vocal about rogue operators and clear about the need to follow the money. Whether one agrees with his tone or not, he has been diligent and engaged.

When he leaves, the issue does not leave with him.

But the departure of a visible advocate matters.

Birmingham now faces a choice.

Continue managing the consequences of a market-led surge in supported exempt accommodation.

Or rebuild its municipal capacity to shape supply, tenure and quality directly.

Thirty-two thousand people live inside this policy.

Follow the money.

Follow the decisions.

And decide who is prepared to lead what comes next.