Forked Tongues, Fashion Crime and the Vanishing Bobby

Policing was being fixed. The system was being shaken up. Action was finally being taken. Strip away the choreography and what remained was remarkably thin.

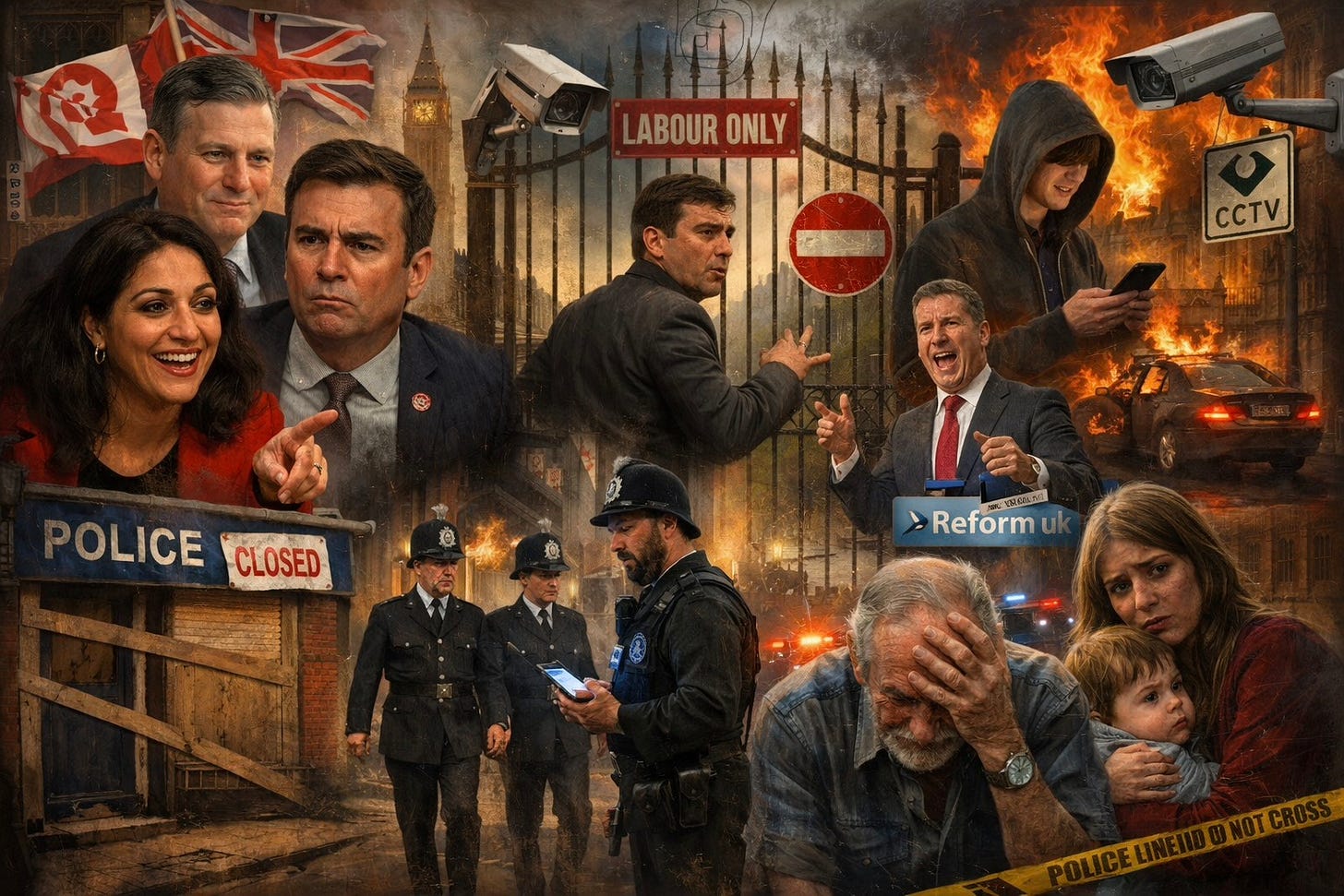

Eighteen months into a Labour government, and well over a decade into Labour stewardship of policing oversight in the West Midlands, this week unfolded as a near-perfect illustration of how modern British politics now operates. Loud where it is cheap. Earnest where it is hollow. Silent where it matters. It began with a burst of tough-sounding announcements about policing, prompt action and restored authority. It ended with the quiet publication of figures showing that police numbers are falling across almost every measure that actually makes people feel safer. Between those two moments lies the real story, not about crime, but about performance, control and a political class that increasingly governs by managing optics rather than reality.

The week opened with the Home Secretary, Shabana Mahmood, energetically banging the social media drum. The message was breathless and urgent. Policing was being fixed. The system was being shaken up. Action was finally being taken.

Strip away the choreography and what remained was remarkably thin.

We were told that 999 calls would be answered more quickly. That officers would arrive at serious incidents sooner. That forces failing to meet expectations would be “visited” by better-performing forces and shown how to improve. Alongside this came familiar language about cracking down on antisocial behaviour and online abuse, signalling moral seriousness in the digital age.

None of this is meaningless. If you are waiting on hold during an emergency, seconds matter. If help arrives sooner, that matters too. Online abuse can be real, corrosive and sometimes devastating.

But this was not a policing revolution. It was basic competence dressed up as reform.

Three things made that clear. First, there was no commitment to more officers. Second, there was nothing about visibility. Third, none of it addressed the simple fact that response times ultimately depend on whether there is anyone available to respond.

Answering the phone faster is not the same thing as having someone to send.

This felt less like policy and more like content. The sort of announcement that emerges when a party machine quietly asks departments to come up with “good news”, any good news, at a moment when the political weather has turned sour. The Prime Minister welcomed the tough tone. Loyal Labour voices applauded. Inside Westminster, the performance landed as intended.

Outside, it barely registered.

That is because it coincided, not accidentally, with a much more revealing act of power. The decision to block Andy Burnham from seeking a return to the House of Commons.

This was not a procedural footnote. It was a signal.

Burnham is popular, electorally credible and carries an independent mandate. In modern Labour, that combination is no longer an asset. It is a threat. The block was sold as strategy. It read as fear. Fear of competition. Fear of unpredictability. Fear of democracy when it cannot be stage-managed.

The seat will almost certainly now fall to Reform UK. Everyone knows it. The party knows it. The public knows it. Which leaves an awkward question hanging in the air.

Does Keir Starmer actually care if Labour loses a seat, if losing it protects his personal position?

Judging by the calculation involved, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that internal control mattered more than electoral consequence. The public response was telling. Not outrage. Not fury. A yawn. Another quiet entry in the mental ledger that says this lot are not what they claim to be.

Seen in that light, the Home Secretary’s sudden enthusiasm for tough policing looked less like conviction and more like cover. A hard face put on quickly while something else unfolded in parallel.

As the week went on, criticism of Starmer did not die down. It grew. Labour defended the indefensible with that familiar, bloodless fluency that turns obvious manoeuvres into supposed statesmanship. Reform, meanwhile, got on with selecting a candidate and promising to throw everything at the by-election. One side managed the narrative. The other acted.

Running alongside all this was another familiar Labour reflex, what might politely be called fashion crime. The policing of online life. Offensive posts. Digital outrage. Social media behaviour elevated into a central law-and-order battleground.

This plays beautifully in politics. It signals moral seriousness. It photographs well. It allows ministers to join the outrage bandwagon and look decisive without confronting the messier realities of street policing. The suspect is a username, not someone likely to resist arrest.

Online abuse can cause real harm. That is not in dispute. But if this is the priority, then give regulators real teeth and let them bite. Do not quietly thin out neighbourhood policing so ministers can perform toughness in comment threads.

And then, at the end of the week, reality intruded.

The Home Office workforce figures landed, and they told a much less flattering story. Police officers down. Police staff down. PCSOs down. Specials and volunteers down. Not a blip. A broad contraction.

This is eighteen months into a Labour government.

And in the West Midlands, it comes after years of Labour ownership of policing oversight. Before Simon Foster, there was Bob Jones. Different men, different presentation, same political assumptions. Trust the experts. Manage the system. Explain the public away.

The West Midlands is not an abstract policy unit. It is Birmingham, the Black Country, Coventry, Solihull. Dense, pressured, diverse. People notice when bobbies disappear. They notice when PCSOs vanish. They notice when police stations close and patrols thin. They notice when reassurance becomes conditional and presence becomes rare.

Every Brit understands something that experts loathe to admit. Life feels better with more bobbies on the beat. Not in a spreadsheet. In reality.

Then the experts arrive to explain that the public is wrong. Visibility is inefficient. Foot patrols are outdated. Numbers matter less than outcomes. The people who fund the system are politely instructed to sit down and let the professionals decide.

That is not just a policing failure. It is a democratic insult.

By the end of the week, the contrast was brutal. Tough talk at the start. Fewer officers at the end. A government performing authority while hollowing out the very thing that gives authority meaning.

People are not angry anymore. They are bored.

And boredom is the most dangerous verdict of all.

It is the sound of a government being quietly marked for removal.

If I was being brutally honest I have to say I forgot about him him. 😮 I felt the role of PCC has been a mixed bag for all 3 of them, yet senior police officers are undoubtedly brilliant politicians - arguable the best in contemporary society. The very nature of what they do gives that collective survival instincts a well honed edge.

I recall writing about Jamieson when I attended a Solihull MBC meeting, for the Birmingham Mail - he led the Labour group then and stood head and shoulders above every other Cllr in the chamber - sorry 😔

Mike,

Curious to see you leap from Bob Jones, WMPCC 11/2012-7/2014, to Simon Foster 5/21 till now. What happened to David Jamieson 8/2014-5/2021? I have watched all of them in public meetings. They all had genuine policies, but each could be distracted by the police's senior officer. Mention anything about traffic management and David Jamieson was attentive.

There were rumours that Bob Jones objected to senior officers all being issued with an Ipad, when they all had a laptop, but he agreed to the purchase.

At one public meeting of the WMPCC advisory board hidden in the agenda was an item to equip officers with pepper spray, replacing the CS (tear gas) spray. It was "passed on the nod" regardless of the escalation involved. The B'ham Mail reporter had not even noticed.

In my opinion all the WMPCC were "played" by the senior police officers, so they will not be missed. Imagery was more important than public accountability.