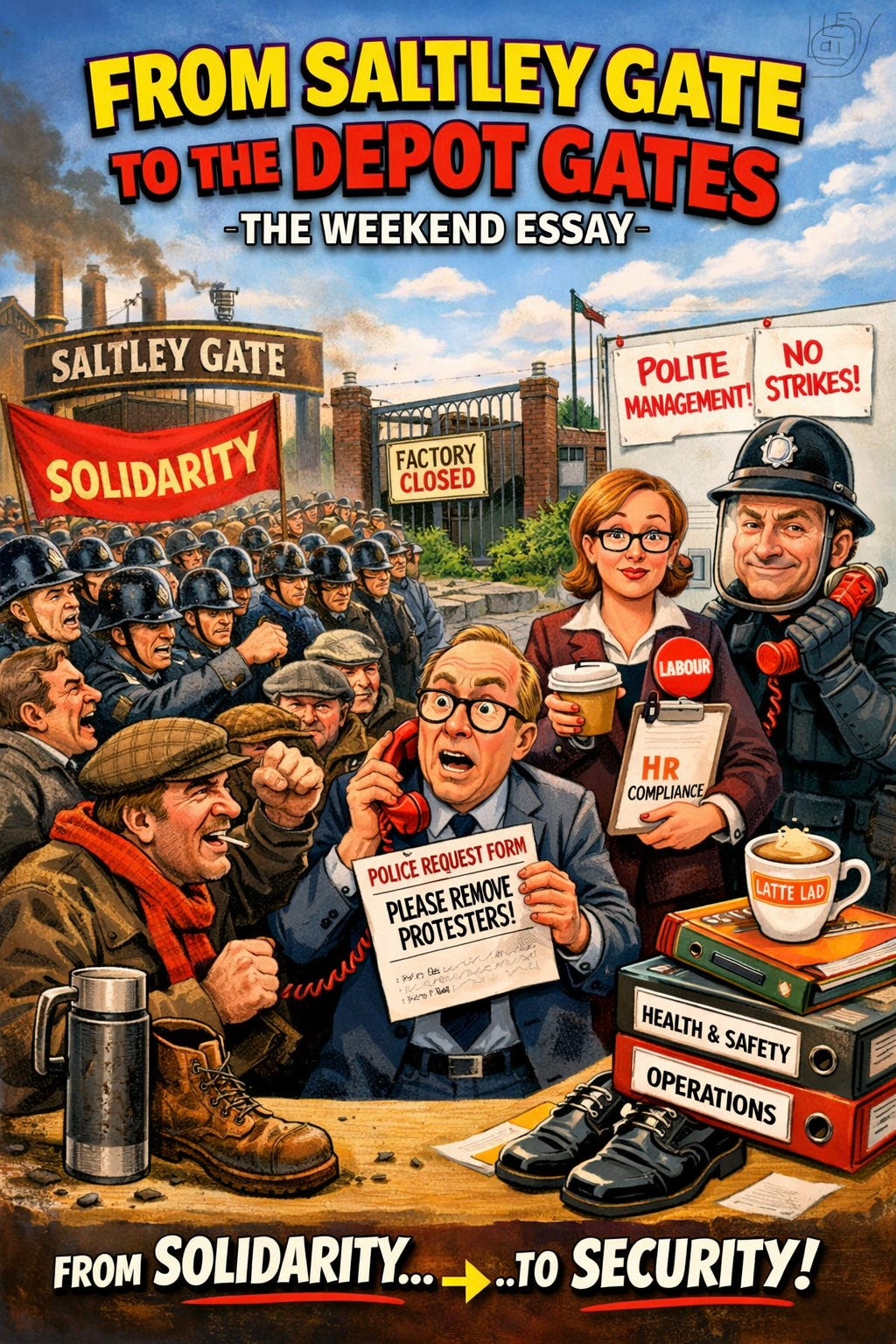

From Saltley Gate to the Depot Gates: Labour, work, power, and what happens when a party forgets why it exists

Faced with a long-running bin dispute, Labour councillors have chosen escalation over political leadership. Letters to police chiefs. Public frustration with police restraint.

This is not a hard-left essay.

It is not nostalgia dressed up as politics.

And it is not a defence of every strike, every tactic, or every decision ever taken in the name of organised labour.

It is a weekend reflection on memory, work, and power, written from the Midlands, by someone who has lived inside Labour’s culture for an entire adult life and refuses to abandon it now.

I am not leaving the Labour Party.

But nor am I prepared to stay silent while it forgets itself.

Saltley Gate was not radicalism, it was recognition

In February 1972, at Saltley Gate, tens of thousands of workers shut down a fuel depot on the edge of Birmingham. Miners were joined by engineers, car workers, foundry workers, refuse workers, men and women who did not formally “belong” to the dispute at all.

They turned up anyway.

My father went. Not because he was an ideologue, but because he recognised something fundamental, that if one group of workers could be isolated and defeated, the rest would follow soon enough.

When I later started work at Birmingham Small Arms, the Guns itself, in the mid-1970s, Saltley Gate was not a romantic tale. It was a benchmark. A supreme act of solidarity. A marker of where the line was.

No one debated whether blocking roads was disruptive. Of course it was. That was the leverage. Power never yields to inconvenience politely requested.

This was not extremism. It was organised Labour behaving as it instinctively understood itself.

I was never hard left, and that matters

I was never regarded by my peers as hard left. I did not fetishise strikes or treat industrial conflict as a virtue in itself. Like many of my generation, I lived through the 1980s and saw reckless disputes in car manufacturing do real damage to industries, jobs, and communities.

And here is the part that matters.

Workers learned.

Unions learned.

Trade unionism corrected itself not because the state crushed it, but because working people understood responsibility as well as solidarity. Discipline came from within, not from police lines or court orders.

That history matters, because it exposes the lie now used so casually, that anyone defending protest or solidarity must be some kind of throwback ideologue.

My anger now does not come from radicalism. It comes from memory.

The miners were right, even when tactics were wrong

The miners’ strike deserves honesty, not caricature.

The miners were right about the central question. The government did intend to do away with coal mining. This was long before any serious green transition. Coal was targeted because it was organised, powerful, and politically dangerous.

Coal mining was not just an industry. It was a backbone workforce.

Yes, the strike did not always reflect democratic process perfectly. Yes, tactics were sometimes flawed. But none of that alters the core truth. The miners were resisting planned industrial extinction carried out for political reasons.

History has vindicated that judgement, even if it remains uncomfortable.

The car workers were often right too

The same honesty must be applied to car workers in the Midlands.

There were reckless moments. There were disputes that hurt productivity and credibility. Anyone who worked through the period knows that. But that is only half the story, and it is the half that has been endlessly rehearsed.

Workers at British Leyland Motor Corporation, particularly in Birmingham, understood something that management and government preferred not to admit.

They knew investment was being starved.

They knew strategy was absent.

They knew decline was being managed, not challenged.

They also knew what a pile of junk the Austin Allegro was, but it was their pile of junk and so that stayed private.

At Longbridge, the idea that Birmingham would cease to be a car-making city was unthinkable. Yet that certainty drained away, not because workers imagined it, but because they could see what was happening before others chose to acknowledge it.

They were not paranoid. They were early.

Birmingham still makes cars, and that matters

Accuracy matters.

We do still make cars in Birmingham.

The Jaguar Land Rover plant at Castle Bromwich remains a major industrial site. Even when production pauses or models transition, the skills, infrastructure, and industrial memory remain.

So it would be wrong to say Birmingham no longer makes cars.

What is true is more troubling.

Birmingham no longer speaks with the confidence of a city that assumes it will always make them.

Manufacturing has shifted from being structural to being contingent. Production is discussed as allocation, platform, competitiveness. All real, all necessary, and all corrosive when they replace the older assumption that making things belongs here.

The Midlands supply chain proves what remains possible. What has faded is the political voice that once insisted manufacturing mattered.

Birmingham now: Labour reaches for the state

Which brings us to Birmingham today.

Faced with a long-running bin dispute, Labour councillors have chosen escalation over political leadership. Letters to police chiefs. Public frustration with police restraint. Calls for protesters to be “moved on quickly” so operations can continue “unaffected”.

This matters because of who is making the call.

This is a Labour authority, acting as employer, pressing the police to intervene against workers and their supporters in an industrial dispute.

The legal friction is the DPP v Ziegler ruling, which reaffirmed that deliberately obstructive protest can be lawful and must be assessed proportionately. Automatic clearance is no longer a reflex.

What angers councillors is not disruption. It is loss of command.

When Labour talks like management

Two Labour councillors have been most publicly associated with this posture, Majid Mahmood and Marcus Bernasconi.

The issue is not personality. It is instinct.

Once, Labour politicians spoke the language of labour. Today, too many speak the language of compliance, operations, and enforcement. Protest becomes an obstruction. Solidarity becomes a risk to be managed.

To anyone who stood at Saltley Gate, that does not look like pragmatism. It looks like desertion.

Reform is not the cause, it is the language vacuum

This is where Reform UK enters the story, and it must be addressed honestly.

Reform speaks a language Labour increasingly avoids. It speaks to people who know what barrier cream is for, who know the price of bread and milk, who understand the drag of minimum-wage work, fatigue, repetition, and necessity.

That does not make Reform right.

But it makes it intelligible.

Labour is not losing voters because Reform has better answers. It is losing them because Labour increasingly sounds like management talking about work, not people who have done it.

Reform sounds angry for workers.

Labour too often sounds angry at them.

The hollowing out from within

The greatest danger to Labour has never been its opponents. It has always been what happens when people forget why they are in public office.

Early Labour figures were flawed, combative, sometimes wrong, but they understood power as a means, not a reward. Too many now inhabit authority without memory, crossing principles because they no longer recognise them as binding.

When power moves on, so will they.

Labour will remain.

Why I am staying

I am not leaving the Labour Party. I refuse to.

Leaving would hand the ground entirely to those who have hollowed it out. Labour does not need fewer people with memory. It needs more who are willing to speak.

Labour was built by people who stood at gates, not people who rang the police about them.

Remembering that is not extremism.

It is continuity.

Saltley Gate still stands. Castle Bromwich still stands. The supply chain still stands.

What is fragile is the voice that once insisted work, production, and solidarity were foundations, not inconveniences.

Some of us still remember it.

Some of us are still here.

And until Labour either rediscovers that voice, or finally admits it no longer wants to, some of us will remain exactly where we are, arguing, insisting, and refusing to pretend that forgetting is the same thing as progress.