From Villa Park to No Confidence: How One Policing Decision Triggered an Inevitable Reckoning

The Villa Park decision exposed something corrosive: a sense that explanation was being retrofitted to justify an outcome already chosen.

When West Midlands Police banned Jewish supporters from attending Aston Villa’s Europa League match against Maccabi Tel Aviv, citing intelligence that later unravelled under scrutiny, the decision detonated far beyond football. What followed was not simply outrage at fans being excluded, but a deeper unease that policing had confused risk assessment with political optics, and authority with narrative control. It is from that moment, and not from any abstract exercise of power, that Shabana Mahmood’s intervention must be understood. Her declaration of “no confidence” in the leadership of West Midlands Police was not theatrical. It was the beginning of an endgame triggered by a single, catastrophic failure of judgement.

This was not a marginal fixture. It was a high-profile European match at Villa Park, involving an Israeli team, played against a febrile international backdrop. That demanded professionalism, proportionality, and clarity. What emerged instead was a ban that appeared to treat identity as proxy for risk, followed by explanations that shifted as scrutiny intensified. Once the justification began to look unstable, the damage was done. Policing authority rests on trust, and trust collapses when the reasoning changes after the decision has already been taken.

How a local decision became a national test

Football bans happen. Policing errors happen. What made this different was the sense that exclusion had been normalised first, and interrogated second. When intelligence is used not as a tool for decision-making but as a shield against challenge, the issue stops being operational and becomes constitutional. That is why the story escaped the Midlands and landed on the national stage.

By the time the Home Secretary spoke, parliamentary anger had hardened and public patience had thinned. Mahmood’s “no confidence” statement did not create the crisis. It acknowledged one that was already visible.

Who really holds the power, and why it matters less than it used to

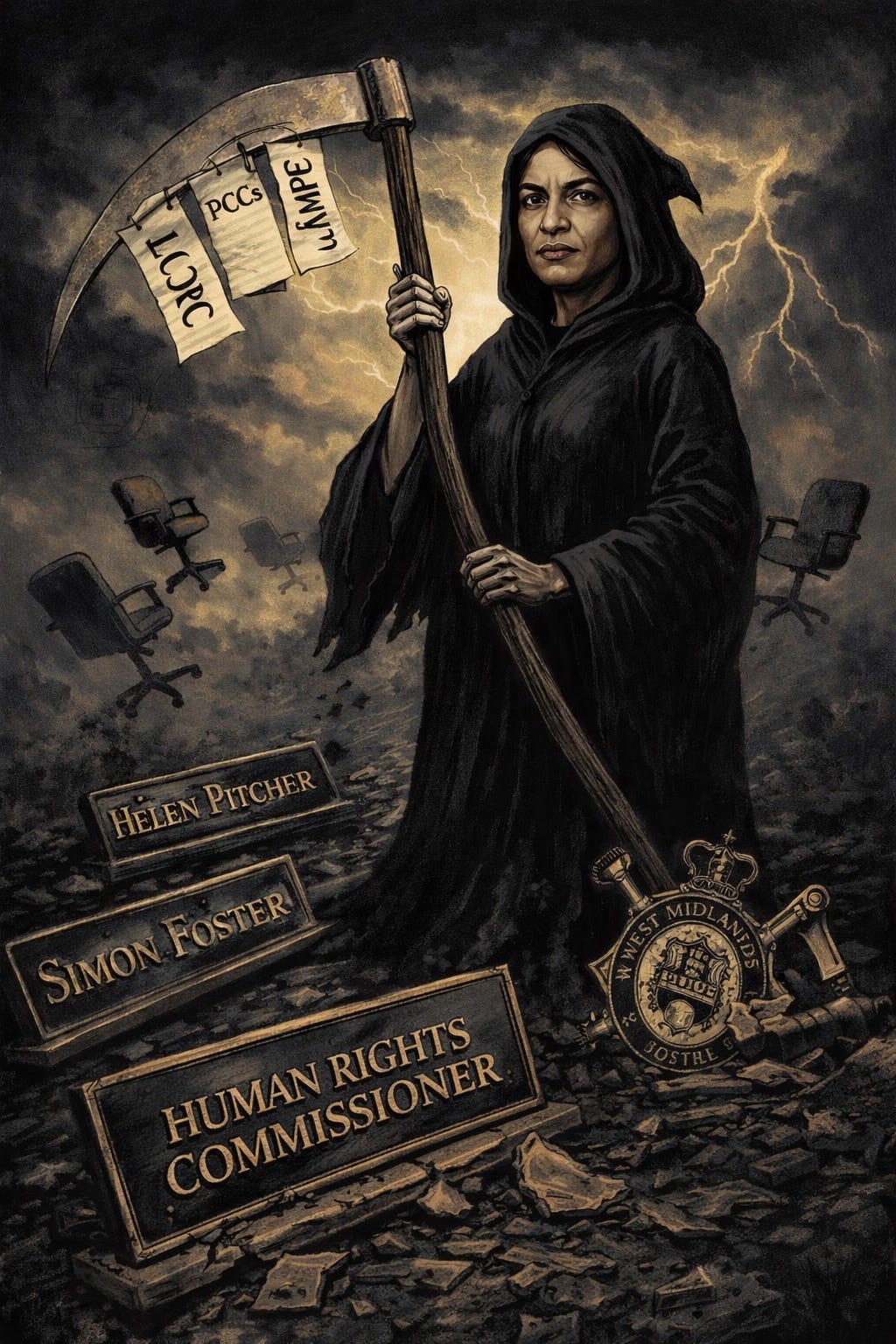

Formally, the Home Secretary does not remove Chief Constables. That responsibility sits with the local Police and Crime Commissioner, in this case Simon Foster.

But politics is not a legal seminar. It is psychology.

Foster remains in post, yet his role has already been marked for abolition. The government has announced the end of the Police and Crime Commissioner model. The office survives for now, but its future has been cancelled. That leaves him in an exposed position: still holding the formal authority to act, while knowing the system he represents has been judged a failure.

In those circumstances, independence becomes fragile. Mahmood does not need to sack Foster to neutralise him. She has already told the country his model of oversight is finished. The question is whether he uses his remaining authority to act decisively, or whether he becomes another casualty of a dying structure.

Why “no confidence” is never casual

In public life, “no confidence” is not just language. It is choreography.

It directs the media’s attention.

It sharpens watchdog scrutiny.

It tells Parliament where the fault lines lie.

And it tells senior officers that the leadership clock has started ticking.

The Villa Park decision exposed something corrosive: a sense that explanation was being retrofitted to justify an outcome already chosen. Once a police force appears to be explaining itself backwards, legitimacy drains quickly. Mahmood’s intervention simply named what many already suspected.

This was never just about one officer

That is why this story does not end with a single individual.

Operational accountability does not exist in isolation. Assistant Chief Constable Mike O’Hara sits close to the heart of public order decision-making. When a major judgement collapses under scrutiny, those responsible for its execution and defence inevitably come under the same spotlight. Senior policing failures rarely conclude with one resignation. They end with a recalibration of leadership, designed to restore authority and trust.

The pattern institutions recognise

There is precedent here.

When Mahmood concluded that the Criminal Cases Review Commission had failed catastrophically in the Andrew Malkinson case, she publicly stated that its chair, Helen Pitcher, was unfit for office. Pitcher initially resisted. Process followed. Pressure mounted. Eventually, she went.

The lesson for public bodies was clear. When Mahmood decides that an institution has failed at the top, resistance may delay the outcome, but it does not change it.

The SAG and CONTEST problem: where boundaries blurred

The Villa Park decision cannot be understood without examining the advisory structures around it, particularly the Safety Advisory Group and the CONTEST counter-terrorism framework.

CONTEST is the UK’s national counter-terrorism strategy, delivered locally through multi-agency boards designed to assess risk and agree proportionate responses. These forums demand neutrality. Political scrutiny belongs outside them, not inside.

That distinction matters.

The letter from Alex Yip, a Conservative councillor, requesting CONTEST scrutiny followed the correct route. It was open, attributable, and political, exactly where politics belongs. He did not participate in the Safety Advisory Group, nor attempt to shape operational advice. His politics were declared, not disguised.

The concern lies elsewhere. It is understood that councillors from more than one party, Labour and Liberal Democrat included, participated in advisory environments without leaving their politics at the door. That is not scrutiny. That is contamination. When political objectives enter spaces designed for professional judgement, advice bends, risk assessments shift, and accountability blurs.

Why this moved so fast

Once advisory neutrality is questioned, leadership becomes exposed. Watchdogs sharpen their focus. Morale falters. Political patience evaporates.

Simon Foster can act and contain the damage, or hesitate and allow pressure to accumulate. Either way, the direction of travel is clear. The abolition of his office removes any incentive to absorb blame indefinitely on behalf of a leadership whose authority has been publicly undermined.

Mahmood does not need to escalate further. She has already spoken, and she has form.

Returning to where this began

It is worth returning, finally, to Villa Park.

Jewish supporters were told they could not attend a football match because of who they were. The justification was framed as intelligence, caution, necessity. That language has an ugly history in Europe, often met with silence.

This time it was not.

What followed was not a Midlands race row or a descent into communal grievance. It was scrutiny. The focus shifted away from identity and onto authority, away from who was excluded and onto who decided exclusion was acceptable. That distinction matters. It is the difference between prejudice being absorbed and prejudice being confronted.

The reckoning that followed was not an attack on policing, nor an indulgence in racial grievance. It was an insistence that exclusion demands explanation, and that explanation demands accountability. When the system faltered, the response was not to turn on a community, but to turn upwards, towards leadership, judgement, and governance.

In that sense, this was not a Midlands story at all. It was a national one. A moment when the country was presented with a choice between quiet acceptance and uncomfortable consequence, and chose, imperfectly but unmistakably, the latter.

I think Richard that OHara is well within the cross hairs, strongly rumoured he may be seeking retirement. I suspect no HMIP £1k or more a day consultancies for him ...

Mike: With the clamour to force resignation or sack Craig Guildford, isn't the Assistant Chief Constable O'Hara equally complicit in this affair? There doesn't appear to me to an equal clamour to dispense with his services, unless I'm missing something. Of course the man at the top of the pile is supposed to be held accountable for the failings of his minions, although sometimes this doesn't happen and someone much lower down the greasy pole finds themselves set up as the fall guy.