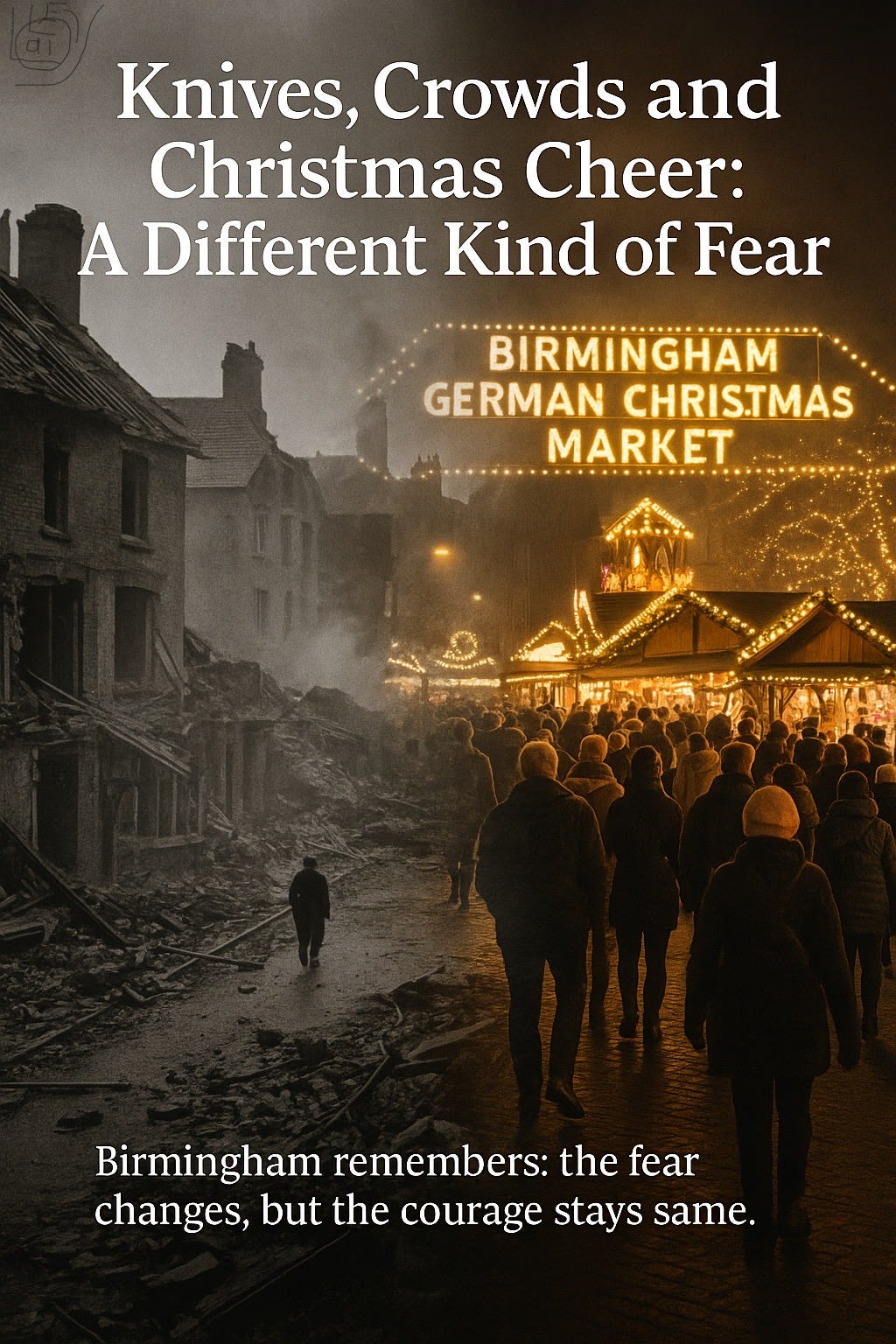

Knives, Crowds and Christmas Cheer: A Different Kind of Fear

One attack on a train a hundred miles away, and suddenly a city hesitates to go and drink Glühwein under the Christmas lights.

Scroll through social media or the local forums and you can feel it. The nervous hum that sits just beneath the chatter. Someone posts a photo of the German Market, wooden huts, fairy lights, the smell of bratwurst and mulled wine, and half the comments talk about crowds, drunks and pickpockets. The other half say they’re not going anywhere near the city centre this year.

And then there’s the bigger fear, the one nobody quite names but everyone feels. The unease that follows an event like the attack on the East Coast train last weekend. Two men with knives. Chaos in a carriage. Ten people injured, nine of them fighting for their lives. Armed police boarding at Huntingdon, people hiding in toilets, others pressing jumpers against wounds. You don’t need to call it terrorism for it to shake you. It was madness, pure and simple, but the result is the same, a train full of terrified people, and a country once again reminded of how thin our peace can be.

It’s easy to see why people get anxious. We’ve had years of grim news, and the idea of stepping into a crowd can feel like tempting fate. But fear has a way of spreading faster than facts. One attack on a train a hundred miles away, and suddenly a city hesitates to go and drink Glühwein under the Christmas lights.

I understand it. Yet I can’t help thinking of my mother.

A Different Kind of Fear

My mother used to talk about fear in a very different way. During the war, an incendiary bomb came through the roof and landed in her bedroom. It didn’t explode properly but buried itself into the mattress and burned through the night, scorching everything in the room with fierce heat yet never bursting into flame. When the family returned the next morning, the bedroom was blackened and ruined, but the house still stood.

They hadn’t been there when it happened. My mother’s family lived in St Luke’s Road, Highgate, right in the city, where the bombs fell thick and fast, but like a lucky few, they’d taken to spending the nights away from the centre. On that night, they were staying at the Crown public house in Monkspath, sleeping above the bar for safety. That simple act of caution probably saved their lives.

The following day, my grandfather was outside loading belongings into the family car when an unexploded bomb in a neighbouring house suddenly detonated. These delayed-fuse devices were a common tactic used by both sides in the war, designed to kill rescuers and cause maximum disruption. The explosion blew the car to pieces. My grandfather survived only because he’d paused to speak to a neighbour; a few seconds differently, and he’d have been gone.

Not long after, my mother was at the cinema on Coventry Road when the sirens went again. Everyone dashed out into the street looking for shelter, only to be strafed by a German fighter. The people in front of her were killed. She never forgot that, the noise, the panic, the sheer chaos of it all.

For her, that was fear. Real, immediate, and all-consuming. So when the IRA bombings began in the 1970s, she didn’t dismiss them, but they didn’t shake her sense of daily life either. She’d seen what war did to ordinary streets, and she wasn’t about to stay home because of the news. Her view was simple: you can’t stop living every time someone tries to make you afraid.

The Fear We Inherit

We don’t live through that kind of horror now, thank heavens, but we seem to live with fear more than ever. It’s quieter, subtler, but always there, a low-level hum that runs through public life. We worry about the tube, the high street, the football match, the concert. Every bag left on a platform, every raised voice in a crowd becomes a potential threat.

Maybe that’s the price of information. My mother had no phone in her pocket pinging her with updates about every fresh disaster. She saw what happened in her own street and nowhere else. We, by contrast, live in an endless newsreel of panic. And so the attack on a train in Cambridgeshire becomes a ghost haunting the streets of Birmingham.

The German Market Mood

The Birmingham German Market should be a tonic, bright lights, music, and laughter in the cold. But this year you can sense the hesitation. Some people call it overpriced tat; others call it a security risk. Online chatter talks about armed police, random bag checks, and the risk of “something kicking off”. It’s a strange sign of the times when people see a Christmas market and think “target” instead of “treat”.

The truth is, it’s probably one of the safest places you could be. Security is tighter than ever, and the police are visible for good reason. But perception counts more than policy. When people feel uneasy, they stay home, and that’s how fear wins without even lifting a weapon.

Perspective, Please

That’s where my mother’s voice still echoes. She wouldn’t have been reckless, but she would have gone out regardless. She’d have gone to the market, bought a sausage, grumbled about the price, and enjoyed it anyway. Because for her generation, the answer to fear was normal life. You didn’t give it the satisfaction of changing your plans.

We could use a bit of that spirit now. The world is no less dangerous, but it’s no braver either. We’ve learned to talk about anxiety but not always to push through it. And maybe, just maybe, it’s worth remembering that a city’s heartbeat depends on its people turning up — on being there, despite the nerves.

The Real Test

Two men with knives on a train do not define this country. They do not define Birmingham, or the German Market, or the way we live our lives. They remind us, yes, of how fragile things can be. But they also remind us of what my mother already knew: that life is precious, unpredictable, and not to be lived in fear.

So by all means, keep your wits about you. But go. Go to the market. Go to the concert. Have a mulled wine, share a laugh, complain about the weather. That’s how you win against fear, by living.

Because the truth is, the lights always shine brighter when you’ve known the dark.

What a great reminder of who we are as a nation.