Life After Parliament, Or How John Hemming Refused to Retire Quietly

With John, long before “biohacking” entered polite committee-room vocabulary, he had already built and sold serious businesses.

Life After Parliament, Or How John Hemming Refused to Retire Quietly

I have known John Hemming since I first wandered into Birmingham City Council in the early 1990s, both of us full of opinions, optimism and hair. We are roughly the same age. John has been rather more successful in business than I have, possesses a brain roughly the size of a small planetary system, and has a deeply irritating ability to understand things involving numbers, systems and cause-and-effect.

I, however, remain clearly better looking. Some balances in the universe must be maintained.

Politically, John has also outperformed me. He became a popular Liberal Democrat MP for Birmingham Yardley in 2005 and held the seat until 2015, when the Liberal Democrats were still being punished by the electorate for the original political sin of our era, reneging on the no-tuition-fees pledge. Yardley returned to Labour, the Lib Dems went into national retreat, and John exited Parliament with that rare thing, his reputation broadly intact.

I, for the avoidance of doubt, remain an unreconstructed Labour Party member. Some habits are incurable.

Despite our political differences, and despite my superior bone structure, we have maintained a healthy relationship over the decades. John may have left frontline politics, but he did not, as some former MPs do, take up golf, consultancy, or the lucrative art of saying nothing for money. Instead, he did what he has always done, he carried on thinking, building, experimenting and, slightly inconveniently for orthodoxy, refusing to stay in his lane.

That refusal, more than anything, explains where he has ended up.

From Parliament to the Back of the Stage

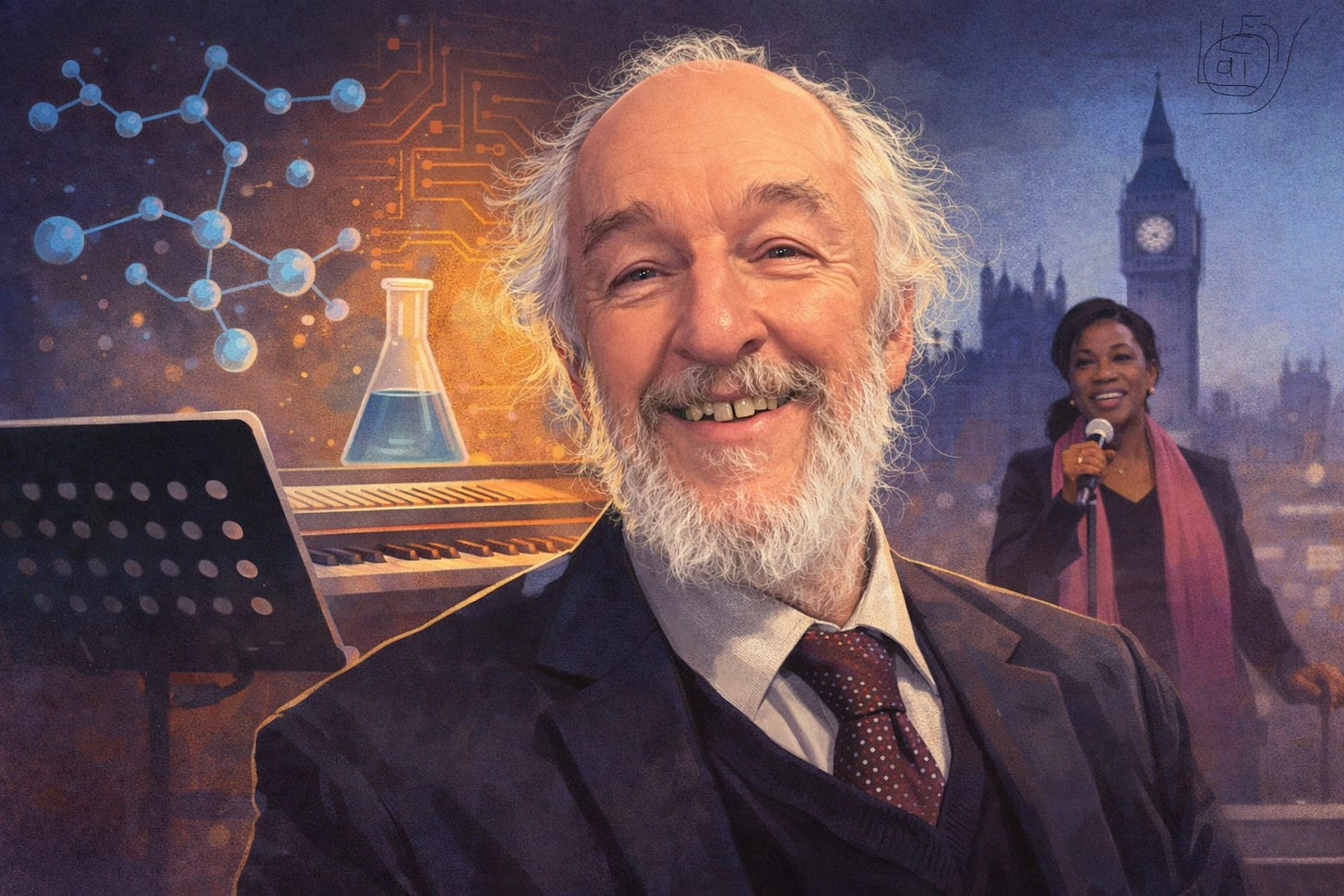

Most people in Birmingham probably know John as a former MP or as a serial tech entrepreneur. Fewer know him as a working musician. John leads and plays in John Hemming and the Jazz Lobbyists, a thoroughly accomplished local band whose singer just happens to be Mrs Olley.

This makes me, by extension, her personal roadie. My duties are tightly defined and physically demanding. I carry the music stand. I attend all the gigs. I offer moral support and occasionally fetch water. Glamour is overrated.

Music, though, is not a retirement hobby for John. It is part of a broader pattern. He does not stop doing things just because one chapter closes. Parliament was a phase, not a destination. The stage, the keyboard, the rehearsal room, these are simply other systems to understand, other moving parts to keep in time.

That matters, because the same instinct that keeps him playing music long after most former MPs have retreated into silence is the one that leads him, later in life, into ageing science and biohacking. John does not file experiences away as “past lives”. He carries them forward and connects them.

The Entrepreneur Who Would Not Sit Still

John’s life after Parliament looks less like a winding-down and more like a controlled acceleration. Long before “biohacking” entered polite committee-room vocabulary, he had already built and sold serious businesses. His software company, JHC Systems, at one point processed around ten percent of UK equity trades. He was early into internet commerce in the 1990s, long before it was fashionable or safe. More recently, he has been involved in Making Tax Digital software, AI ventures, and a string of companies whose names suggest an unhealthy familiarity with deadlines, budgets and the phrase “under budget”.

This matters, because what follows is often dismissed, lazily, as eccentricity.

It is not.

It is continuity.

John has always been interested in what happens when complex systems drift out of balance, and whether small, well-placed interventions can stabilise them again. Markets. Software. Organisations. Now, increasingly, biology.

Biohacking Comes to Westminster

On 20 January 2026, John reappeared in a different guise before the House of Comm0ns, giving oral evidence to the Science, Innovation and Technology Committee as part of its weekly innovation showcase. He was introduced not as a former MP, but as a representative of a biohacking initiative looking at ways to improve health through small-molecule interventions.

This is where the word “unorthodox” starts doing some heavy lifting.

John explained that he has a scientific background, studied natural sciences at Oxford, specialising in physics, before moving into commerce rather than academia. He then did something guaranteed to make British institutions shuffle in their seats, he admitted that some of his experimental work involves self-experimentation.

Cue the polite parliamentary eyebrow-raise.

John, being John, responded by pointing out that several Nobel Prize winners advanced science by experimenting on themselves, and that the defining test of science is not comfort or pedigree, but whether results can be replicated. This did not make him universally popular. It did make him extremely hard to dismiss.

The committee listened. Some members openly admitted that the molecular biology went straight over their heads. Others, with backgrounds in ageing and neurodegenerative disease, followed the argument closely and asked for further material. Parliament, John observed dryly, has become more scientific since his day.

Only a bit. But progress is progress.

Ageing as a Systems Problem

Strip away the jargon and John’s core idea is surprisingly simple.

Ageing is not driven by one catastrophic failure, but by a slow loss of efficiency in the cell’s power supply. The mitochondria, tiny structures inside our cells that generate energy, become less efficient over time. As they do, the signals they send around the cell change.

Those signals influence which genes are switched on or off and how well the body carries out routine maintenance. When the signalling degrades, the body becomes incrementally worse at doing the dull but essential jobs. Bones thin. Skin loses elasticity. Lenses cloud. Nerves struggle. Not because the blueprint is wrong, but because the execution is.

If you want a metaphor that works at the pub, imagine an old house. The appliances still function. The structure is sound. But the wiring is degrading. Lights flicker. Heating behaves oddly. Everything works, just not as well as it once did.

Most approaches to ageing try to replace the appliances, rebuild the kitchen, or knock through a wall and hope for the best.

John’s instinct is different.

He thinks the place to start is the wiring itself.

In this metaphor, you do not demolish the house or redesign it from scratch. You identify which cables are dangerously degraded, remove the worst of them so they stop interfering with the rest of the system, and encourage the house to prioritise maintenance over endless extensions. Fewer conservatories, more time in the fuse box.

Translated back into biology, that means helping the body recognise and clear out its weakest cellular power units, and nudging it into a mode where repair and housekeeping take precedence over constant growth. It is less about dramatic rebuilding and more about regular, intelligent maintenance.

John’s hypothesis, then, is not that ageing is a bug in the software. It is that ageing is what happens when a system designed to prioritise growth early in life is forced to run for decades without sufficient attention to upkeep.

That framing matters, because it completely changes what you try to fix.

Cleaning Rather Than Rebuilding

This way of thinking explains why John is drawn to interventions that encourage the body to clean house rather than endlessly expand.

One of the most discussed examples is rapamycin, a compound that nudges cells away from growth mode and towards maintenance mode. In simple terms, it encourages the body to spend less energy building new extensions and more energy clearing out what no longer works properly.

In animal studies, this approach has repeatedly extended lifespan. In humans, the evidence is necessarily messier. There are no clean, decades-long trials. Instead there are biomarkers, shorter studies, careful monitoring, and a growing body of self-experimentation.

John’s controversial view is that occasional, high-intensity “spring cleans” may be preferable to constant low-level suppression, which can dull the immune system over time. He documents his own experiments in detail, measuring, recording and adjusting.

You do not have to agree with him. Plenty of people do not. What matters is that he is not guessing. He is treating the body as a system that can be observed and interrogated.

Why Parliament Paid Attention

What struck me watching John at Westminster was not the density of the science, but the tone. He was not selling miracles. He was explicit about uncertainty, side effects, regulatory barriers and limits. He talked openly about the awkward fact that cheap, naturally occurring molecules are difficult to fund or regulate in systems built around expensive patented drugs.

There was humour too. A line about “expensive urine” as the side-effect of over-regulation landed better than some ministerial jokes I have heard.

This is where John after Parliament becomes more interesting than John in Parliament. Freed from party discipline, media cycles and the daily theatre of outrage, he has become exactly what politics claims to want but rarely tolerates, an independent thinker prepared to sit between disciplines and ask questions that do not fit neatly into funding categories.

The Thread That Never Broke

From software systems to parliamentary scrutiny, from live music to mitochondrial power supply, John Hemming’s post-parliamentary life looks chaotic only if you expect people to narrow with age. In fact, it is remarkably consistent. He has always been interested in systems, how they work, how they fail, and how small interventions can have disproportionate effects.

Some people leave Parliament and spend the rest of their lives explaining why they were misunderstood.

John left and got on with the next problem.

As for me, I will continue attending the gigs, carrying the music stand, and watching with mild amusement as my old political acquaintance refuses to behave like a retired politician. Brains the size of planets are hard to switch off. Better, perhaps, to let them wander into ageing science and see what happens.

And if it all comes to nothing, at least the band is still very good.

Superb analysis. John is and always will be a one off.