Not a One-Man Show: How Emotion Broke a Football Match in Birmingham

Intelligent, engaged people abandon logic when moral emotion takes hold.

When institutions fail, we like to believe it is because one person got it wrong. A bad call. A weak leader. A single lapse of judgement that can be isolated, corrected, and forgotten.

It is a comforting fiction.

The decision to bar supporters of Maccabi Tel Aviv from Aston Villa’s European fixture at Villa Park does not fit that story. This was not a one-man show. It was a collective failure, spread across roles that should never have allowed emotion to outrun evidence.

At its core, this is not really about football, and it is not even primarily about Israel and Gaza. It is about something more uncomfortable.

It is about how intelligent, engaged people abandon logic when moral emotion takes hold, and how institutions fail when those people carry that emotion into roles that demand neutrality.

We are living in a moment where Gaza has become a moral accelerant. It sets temperament. It fixes frame of mind. It does not remain politely outside the room. It walks in with people, sits beside them, and quietly shapes how they interpret risk.

If you believe Israel’s actions are indefensible, you may find yourself treating anything associated with Israel as inherently volatile, even a football match in Birmingham. If you believe Israel’s actions are entirely justified, you may find yourself dismissing all concern as political pressure or bad faith.

Either way, logic is already compromised.

The job of public officials is not to be free of feeling. That is impossible. Their job is to prevent feeling from substituting for method.

When a match becomes a proxy war

The exclusion of away supporters was framed as a public-order necessity. That framing matters, because it places the decision firmly in the realm of evidence, intelligence, and proportionality, not politics.

The Home Affairs Committee understood this immediately. Its questioning focused not on sentiment, but on process: what intelligence was relied upon, how it was tested, and whether alternative options were genuinely considered.

The Committee’s decision to recall witnesses and seek clarification was a clear parliamentary signal. Committees do not lightly say, in polite Westminster prose, “come back, because we are not convinced”.

What troubled MPs was not disagreement. It was uncertainty about whether narrative had been allowed to stand in for fact.

Emotional contamination, and why it matters

Emotional contamination occurs when moral anger or fear shapes judgement while masquerading as rational assessment. The person affected rarely realises it is happening. They believe they are being careful. They believe they are being responsible.

This is why it is dangerous.

In emotionally charged contexts, the loudest voice often sounds like the most urgent one. Influence begins to look like evidence. Caution is mistaken for complicity.

This is not a partisan problem. It cuts both ways. That is precisely why institutions exist: to restrain the human impulse to decide first and justify later.

Which brings us to the standard against which all actors in this story should be judged.

Neutrality is not a personality trait. It is a professional skill. And like any skill, it must be actively defended under pressure.

Exhibit A: Amsterdam and the discipline of method

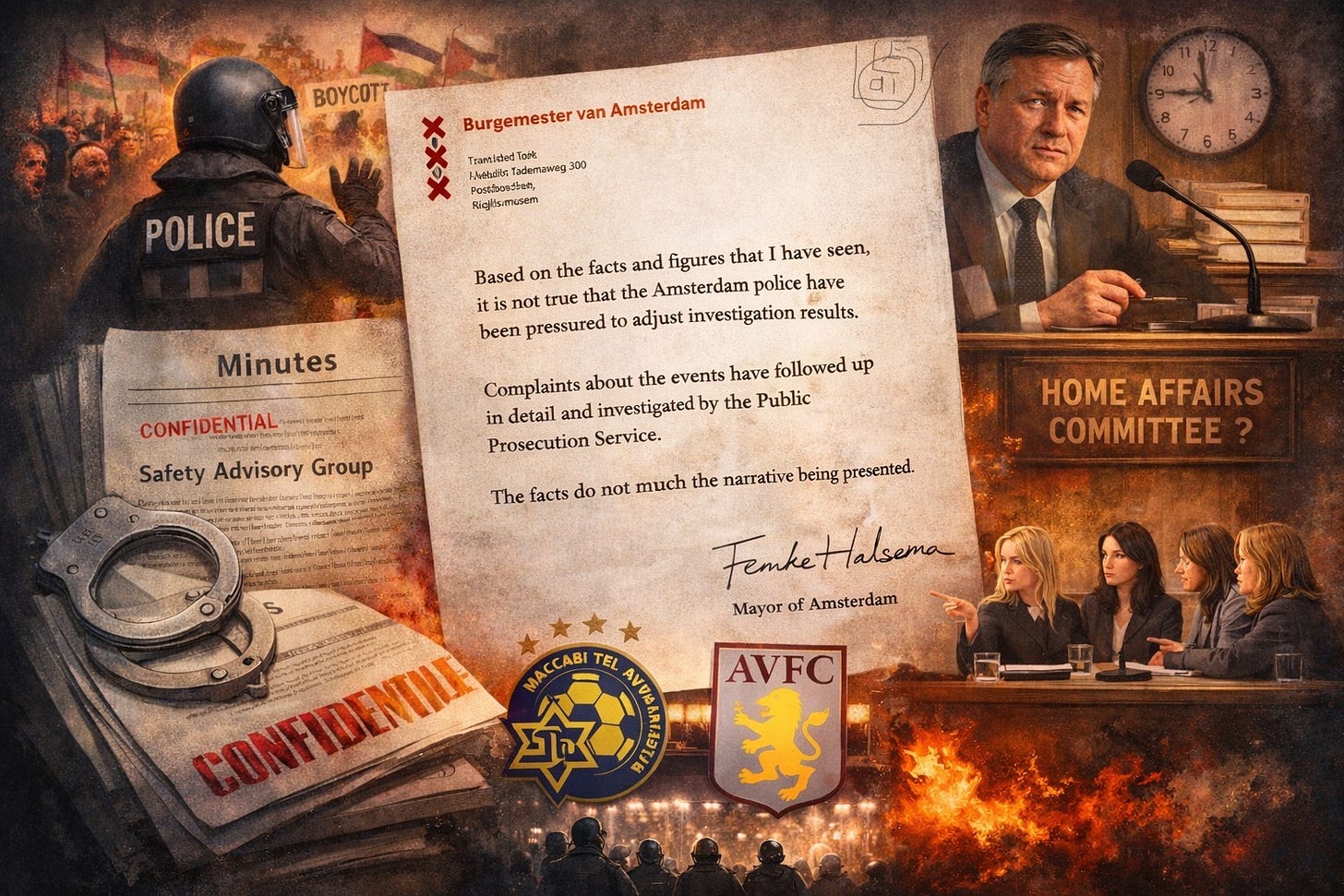

The most instructive document in this saga is not a police briefing or a council minute. It is a letter from Femke Halsema, the Mayor of Amsterdam.

In that letter, she states plainly that the “facts and figures” relied upon elsewhere do not match the claims being made about events in her city. She rejects any suggestion that Amsterdam police were pressured to alter facts, and she anchors her position in published reports and completed investigations.

This matters not because Amsterdam is morally superior, but because it demonstrates something vital.

Halsema is a political actor. She has views. She operates in a city that has itself been deeply affected by protests, tension, and violence connected to the Gaza conflict. She is not neutral in the abstract.

Yet in her institutional role, she does something very specific. She separates sentiment from method. She insists on documents. She points to investigations. She resists being used as a narrative prop.

That is what neutrality looks like in practice.

Not silence. Not moral purity. But discipline.

The Safety Advisory Group, and the problem of role contamination

Safety Advisory Groups are meant to be dull. Their legitimacy rests on process, not passion. They exist to assess risk, not to arbitrate global injustice.

In this case, questions have rightly been raised about the role of councillors within the SAG and whether political identity and aspiration were adequately separated from safety governance.

This is not an accusation. Councillors are political actors by definition. The public expects them to hold views.

The question is whether, in this instance, the record demonstrates the same discipline of neutrality shown by Amsterdam.

Were decisions clearly anchored in documented risk assessments. Were alternative mitigations seriously explored. Were minutes transparent enough to show how conclusions were reached.

If those answers are unclear, that is not proof of bad faith. But it is evidence of vulnerability. When politics enters the safety room, neutrality must be defended more actively, not assumed.

When the paperwork fails, accountability fails with it

One final detail matters, because it reveals how institutional failure is locked in.

At the Home Affairs Committee session on 6 January, Mr Brooks, the senior Birmingham City Council officer with operational responsibility for the Safety Advisory Group process, appeared in person to apologise for the quality of the minutes.

Brooks was clear that he did not personally draft the record. That is not the point. At this level of seniority, responsibility is not clerical, it is operational. The duty is to ensure that systems function, that records are reliable, and that accountability is preserved.

Minutes are not a courtesy. They are the mechanism by which emotion is disciplined, disagreement is captured, and decisions are made defensible. When that mechanism fails, neutrality fails with it.

An apology acknowledges error. It does not remedy it. And at senior operational level, repeated failure to ensure a reliable record is not a minor shortcoming. It is a fundamental professional deficiency.

O’Hara and the difference between professionalism and neutrality

Assistant Chief Constable Mike O’Hara sits at the centre of this controversy not because of ideology, but because of method.

There is little evidence that he is a partisan figure. He does not posture publicly. He does not indulge in social-media signalling. He presents as a well-cultivated professional.

But professionalism is not the same as neutrality.

Neutrality is proven only in decision-making under pressure.

In parliamentary evidence, O’Hara appeared uncomfortable when pressed on the distinction between intelligence and assumption, and on claims attributed to community positions that later required correction. In a politically charged environment, that lack of precision matters.

This is not an isolated concern.

In a separate and very different case, the arrest of Ben Walker, a Romany man accused of threatening a senior Black public official, the policing response was widely described as disproportionate. Escalation preceded verification. Theatre overtook restraint. Basic investigative discipline faltered.

What links the Walker case and O’Hara’s appearance before the Home Affairs Committee is not ideology, but incapacity under pressure. In both settings, escalation preceded verification, and narrative outran evidence.

At this level of command, repeated failure to defend neutrality is not a minor flaw. It is a fundamental professional deficiency.

The uncomfortable question

When the same patterns appear across different cases, it becomes legitimate to ask a hard question.

Is neutrality a skill that must be actively defended, and if so, what happens when senior figures repeatedly fail to defend it under pressure.

This is not about accusing individuals of prejudice. It is about recognising that fear of being on the wrong side of a moral storm can be as distorting as malice.

Institutions fail not because people are evil, but because they are human.

Who can we trust

The answer is not heroes. It is method.

We trust documents that can be examined. We trust transparent reasoning. We trust minutes that show how decisions were reached. We trust oversight that asks awkward questions and insists on clarity.

And we trust public officials who understand that their most important duty, in the most heated moments, is not to reflect the mood of the room, but to resist it.

This controversy is not just about Jewish fans, or Palestinian solidarity, or one football match.

It is about whether our institutions can still tell the difference between threat and temperature.

Because the moment emotion becomes a substitute for evidence, everyone loses.

Football becomes a proxy war. Communities become symbols. And policing becomes theatre.

This was not a one-man show.

Which is precisely why it matters.

Thank you - that's very kind. I do get a dry at times but try to not let flow out into my work.

Great article Mike ! It really gets to the meat of what we , as responsible leaders ,

need to be aware of and be better at !