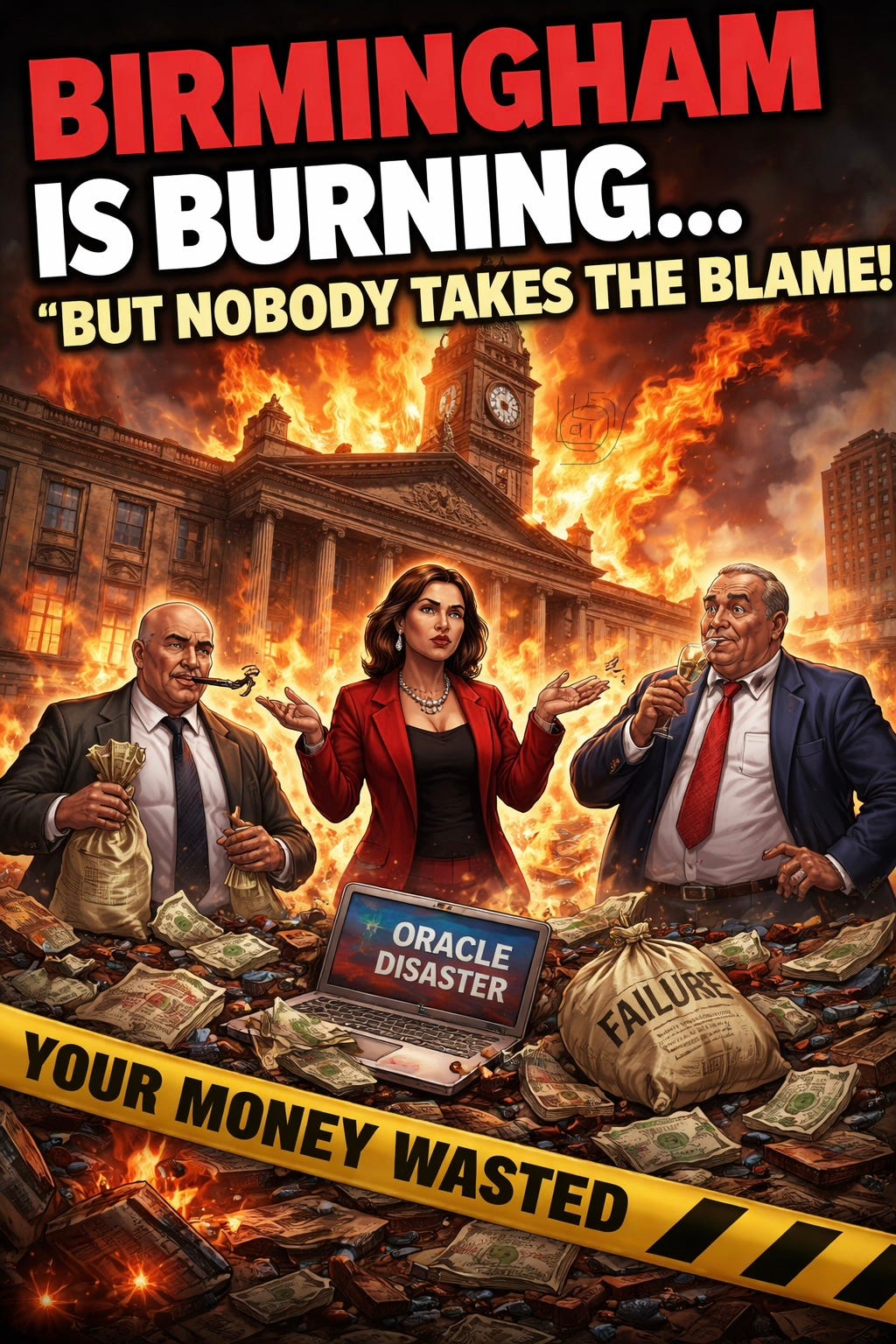

Oracle, Birmingham, and the free pass for failure

The City pays the bill, but nobody takes the blame

Let me put this simply.

Birmingham City Council spent millions of pounds on a computer system called Oracle. It was meant to help run the council’s finances, pay staff, manage procurement, and keep essential services ticking over. Instead, it became part of a wider collapse in financial control that ended with Britain’s largest local authority effectively declaring itself bankrupt.

That is not hyperbole. It is now a matter of public record, set out in committee papers and a formal Public Interest Report accepted by Full Council.

To understand why this matters, it helps to understand what Oracle actually is.

Oracle is what’s known as an ERP system, Enterprise Resource Planning. Strip away the jargon and it means this: it is the software that tells an organisation where its money is. It is the system that pays staff, tracks spending, reconciles bank accounts, and allows leaders to know whether they are solvent and compliant.

For a council, an ERP system is not a luxury or a side project. It is the central nervous system. When it works, nobody notices. When it fails, the organisation is flying blind.

So when Birmingham’s ERP failed, this was never “just an IT problem”. It was a governance failure.

And that is where the real scandal begins.

When failure is absorbed, not owned

When ordinary people mess up, miss rent, fall behind on council tax, or make a mistake, there are consequences. Letters arrive. Threats follow. Enforcement escalates. There is little sympathy and no margin for error.

But when senior officers and politicians preside over failure on a massive scale, when millions of pounds of public money are wasted and core services for schools, nurseries, colleges, housing and families are thrown into disarray, something very different happens.

Nothing.

No one is hauled in and told: you failed, you are responsible, this ends here.

Instead, the system absorbs the failure. It talks about lessons learned. It commissions reviews. It arranges quiet exits. It moves on.

It is as if incompetence at the top comes with a free pass.

This is not an attack on public servants as a group. Many work extraordinarily hard in difficult circumstances. This is a challenge to a culture that too often treats accountability as an optional extra rather than the foundation of public trust.

Oracle is the case study. Accountability is the real story.

From business case to breakdown

The Oracle programme did not arrive as a disaster waiting to happen. It arrived with the familiar language of modernisation. Replace ageing systems. Standardise processes. Improve visibility. Save money.

Cabinet approvals were given. Business cases were signed off. Timelines slipped. Assumptions were revised. Warnings appeared in reports. Yet the programme rolled on.

By April 2022, Oracle went live.

Within a year, the council was publicly acknowledging serious problems. By mid-2023, it was clear that core financial controls, including bank reconciliation, were not functioning properly. When a council cannot reliably reconcile its bank accounts, it does not know where its money is.

That is not a technical inconvenience. That is existential.

The Public Interest Report, issued in 2025, confirmed what many already suspected. This was not a single mistake. It was a pattern of weak governance, poor escalation, and overconfidence in recovery plans that did not deliver.

Even now, the story is not over. Re-implementation continues. Timelines move. Risk ratings remain high. The shadow of Oracle still hangs over Birmingham’s ability to function cleanly.

The part that sticks in the throat

When councils fail at this scale, the immediate consequences are rarely felt by those who made the decisions.

They are felt by residents.

They are felt in stretched services, delayed responses, distracted management, and frontline staff forced into workarounds. They are felt by people living in social housing, by parents navigating pressured schools and nurseries, by communities told there is no money left.

And yet, when you look for the moment of consequence, the moment someone stands up and says “this was my responsibility”, it rarely comes.

Instead, there is a quiet departure. A settlement. Often an NDA. A clean reference. A fresh start somewhere else.

That is not just a Birmingham problem. It is a British local government problem.

And it creates the most corrosive incentive imaginable: failure without consequence.

Asking the obvious question

I did not approach the political parties to demand heads roll retrospectively. That moment has likely passed. I asked something far more basic.

When the next major failure happens, and if nothing changes it will, do you believe there should be personal accountability for senior officers and elected members, or do we continue with lessons learned and business as usual?

The responses were revealing.

The Conservative group leader replied with a detailed position. He spoke about excessive delegation to unelected officers, the use of gagging clauses and pay-offs, weak transparency, and a culture that allows responsibility to be deflected rather than owned.

The Liberal Democrat group leader replied with a different but complementary argument. He described how councils are incentivised to pay failing officers off quickly to avoid litigation, and how this corrodes governance over time. He proposed independent external reviews of major failures, with the power to force public reckoning rather than quiet burial.

Two parties, two traditions, one shared conclusion.

The current system does not work.

Labour, who run Birmingham City Council and oversaw the Oracle programme, did not reply.

More than that, whenever Labour are questioned publicly about Oracle, there is still no straight answer. The response drifts to complexity, to side issues, to everything except accountability itself.

People are entitled to draw their own conclusions from that.

The accountability gap

Local government often displays a split personality.

When it is time to cut services, raise council tax, or tell residents that difficult choices are unavoidable, responsibility is crystal clear.

Residents pay.

But when it is time to account for strategic failure at the top, responsibility becomes foggy. Collective decision-making. Officer advice. Historic context. Process.

Democracy is not just a ballot every four years. It is a culture of responsibility between elections.

Right now, too much of local government behaves as if responsibility is optional once you reach a certain level.

What needs to change

This does not require a revolution. It requires spine.

Transparency by default, not buried detail. Scrutiny that cannot be quietly neutered. An end to the routine use of NDAs to mask failure. Independent mechanisms to examine major breakdowns without fear or favour. And above all, a cultural shift that says clearly: when you are trusted with public money and public services, you do not get a free pass for incompetence.

Failure may happen. How it is handled defines the institution.

The real scandal

The scandal is not just Oracle.

The scandal is that millions can be lost, services disrupted, and public confidence shattered, and yet business as usual remains the default response.

Birmingham deserves better than that.

And the people who pay the price when things go wrong, especially those with the least slack in their lives, are entitled to say so.

Mike. Good article. I am fairly sure that BCC had a working ERP system based on SAP prior to the Oracle debacle. So why did they change? I know that SAP ERP was being superseded by a new product called SAP S/4HANA but surely if the earlier system was to be replaced, the software company would have a suitable strategy to transition to the later system without too much disruption? Has to be better than what appears to have happened, replacement by a totally new system with incompatibilities.

From my experience of 25 years in the civil service, introduction of new systems never improve matters a great deal. The reasons are completely overlooked because planning does not include the period between installation and total completion of staff training. Think about that. Then add in the habit of senior management to grasp minor details of the process and use them as proof of their knowledge of the updated system. Next, it is senior management who will determine (read, anticipate) output levels of work and profit (where appropriate). If over optimism on those levels encounters uncertainty at the new machines, the result will be a slow descent into backlog, culminating in chaos, which will be concealed as best can be done by those who know or fear they will carry the blame, whether guilty or not. Now apply this to, for instance, Birmingham. Or I could offer you Armley Prison in Leeds, where an American computer system was installed which recorded automatically the offence and verdict. All went well, until an officer pressed the wrong button, and some poor soul, who was definitely not sentenced to death as it was no longer legal in the UK, was registered as being under penalty of death under USA law. Initially that looks amusing. It wasn't, as the system had no means to alter or delete the entry. It took 3 days of telephone work between Armley and the US company to retrieve a British prisoner from an American death sentence! This is a true story, told to me by my prison officer husband, working there in the 1990s. No one had checked the system before it was ordered, or installed, or put into use. When computers were first brought into the office I was working in, we had to have special eye tests. If we needed spectacles, the civil service paid for them (NHS basics, of course). Our training was about one week maximum, less for me as I only supervised so what did I need to know about details.....and I am referring to the earlier department now known as DWP, from which I am long retired. Computers may be remarkable when they are working, but it still relies on the operators knowing what they are doing with input. When I started work there, I got advice about a simple machine that sent tape messages to a central system once a day. If it doesn't work, I was told, Give it a good kick underneath. I never had to do that, as it always worked. The same did not apply to computers, but kicking didn't work either.