Papers Please? Not in Britain

ID cards were first brought in by Neville Chamberlain, Birmingham’s own Prime Minister, as a wartime measure in 1939. Winston Churchill scrapped them in 1952 after public patience ran out.

Keir Starmer wants to revive the idea of ID cards with a shiny digital twist. History shows it will not end well.

The Wartime Exception

It comes as no surprise that the only time we Brits have ever been forced to carry ID cards was during the dark days of the Second World War. They were introduced in 1939 by Neville Chamberlain, the famous Brummie who was then Prime Minister, under the National Registration Act. The cards were meant as a wartime emergency measure: rationing, conscription, and spotting enemy agents. Fair enough when the Luftwaffe was overhead.

What’s less well remembered is that the cards stuck around long after the war ended. Labour kept them going right through the late 1940s, and even when rationing was winding down, the requirement to carry your little brown card stayed. By 1952, seven years after VE Day, people were heartily sick of it. The only folk who really loved the system were the police, who found it ever so handy to demand “your papers, please” whenever it suited

Willcock v Muckle: The Turning Point

That creeping culture of convenience is what brought about the case of Willcock v Muckle in 1951. Here’s how it unfolded. In December 1950, a motorist called Harry Willcock, a Liberal councillor and insurance broker, was stopped for speeding in Finchley. The constable asked for his identity card. Willcock flatly refused, saying, “I am a Liberal, and I am against this sort of thing.” He was prosecuted, convicted, and appealed.

The case went up to the High Court, presided over by Lord Chief Justice Rayner Goddard. Goddard was the man the press called the “hanging judge”: stern, ultra-traditional, an old fart of the first order. Law students muttered that he was living proof of Dickens’s old line, “the law is an ass.”

But in this case, Goddard surprised everyone. Yes, he upheld the conviction, because the law was still on the books, but then he tore into the authorities. He said the Act had been passed for wartime security, not as a general convenience for the police to demand papers at will. It was a stinging rebuke from a man not known for liberal sympathies. And it gave public voice to what most Britons were already thinking: the war was over, and this was nonsense.

The press picked it up with relish. Headlines called the ruling “the death knell of the ID card,” and editorials fumed that people were being treated like suspects in their own country. Within months, Churchill’s new government agreed and scrapped the whole system in 1952.

Blair’s Paper Chase

That should have been the end of it, but of course it wasn’t. Tony Blair revived the idea in the 2000s, dressing it up as a way to tackle terrorism after 9/11 and 7/7. We were told it would stop fraud, secure borders, and make us all safer. The proposed scheme was vast: biometric data, fingerprints, iris scans, a central database to track every move.

And the public hated it. Civil liberties groups tore into it, the media savaged the cost, and ordinary people bristled at the thought of being fingerprinted like suspects. The Conservatives under David Cameron promised to scrap it, and when they got in with the Lib Dems in 2010, that was exactly what they did. The biometric cards were ceremonially shredded in front of the cameras.

The message was clear. Britain does not do compulsory ID.

Starmer’s Digital ID Bonanza

Fast-forward to today and here we go again. Keir Starmer has decided Britain must now have identity cards, though to be modern he calls it a digital ID scheme. He insists it is the answer to “stopping the boats,” clamping down on illegal working, and tightening the borders.

In his own words: “You will not be able to work in the United Kingdom if you do not have digital ID. It’s as simple as that.” By the end of this Parliament, he promises, it will be mandatory for anyone wanting to work legally in Britain.

On paper, he makes it sound less draconian. You will not have to carry it everywhere. The police will not be able to pull you over and bark “papers, please.” For those without smartphones, there will be a free plastic card. Its use, he says, will be limited to “Right to Work” checks.

But let’s be blunt: Starmer is deluded if he thinks this will stop illegal immigration or illegal working.

Why It Will Not Work

• Illegal workers do not play by the rules.

They are not lining up to register for a shiny new digital certificate. They are already off the books, working cash in hand, often for a third of the going rate. A digital barrier at the front door means nothing if you are slipping in through the side.

• Employers are the weak link.

The truth is, whole industries in Britain rely on cheap, off-the-books labour. A digital ID does not change the dodgy boss who is happy to pay £40 for a 12-hour shift, no questions asked. Until you hammer the demand side, the supply will keep flowing.

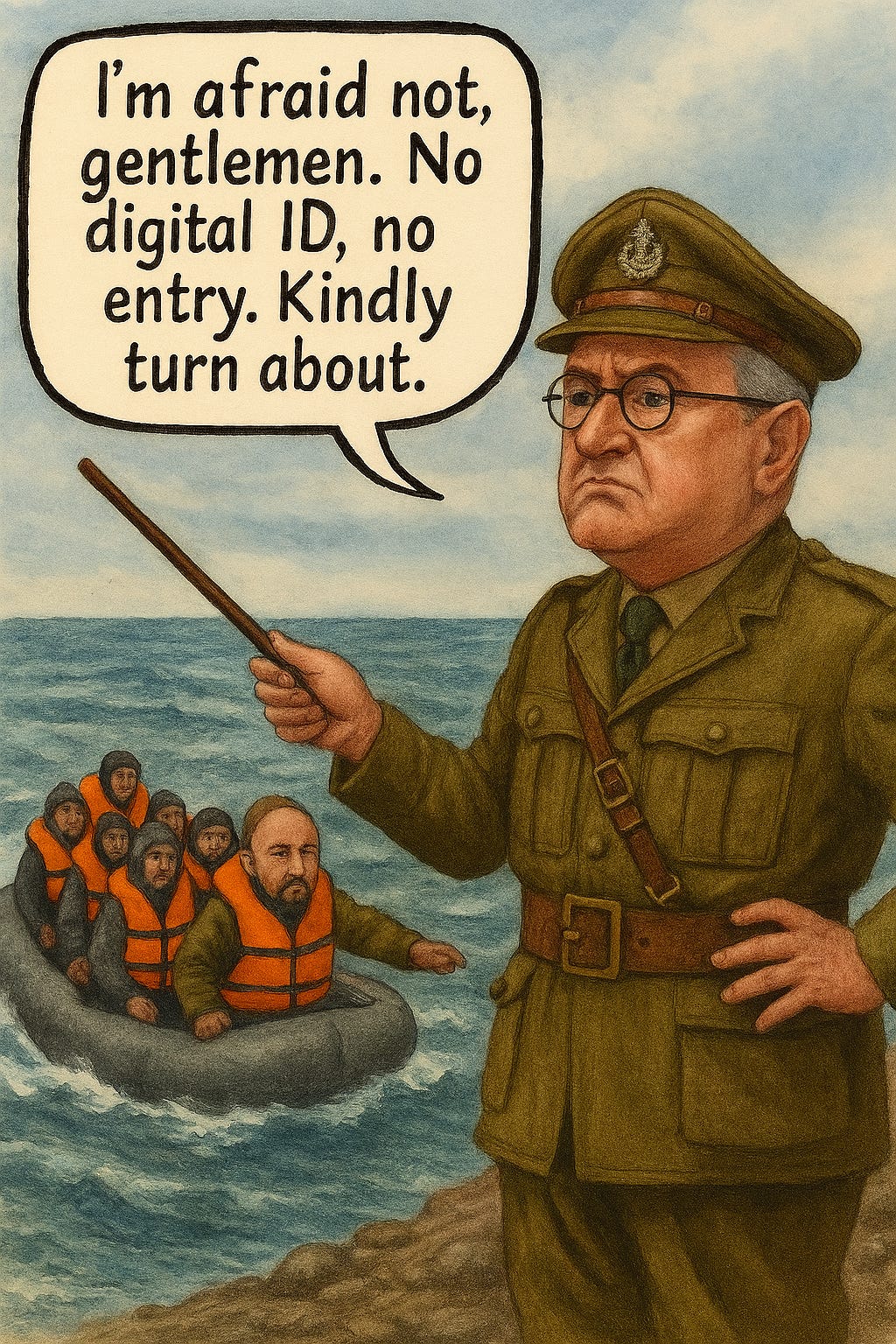

• The “we cannot stop the boats, so we will ID everyone” logic.

Starmer clearly thinks he is being tough on migrants, hoping it will shift the polls for Labour. But I can tell him, as sure as eggs are eggs, it is not going to work. Whatever he says about stopping the boats or smashing the gangs with ID cards is fantasy politics. You might as well nail a sign on the White Cliffs of Dover saying: “Only those with ID cards may enter.”

The Big British Problem

We have been here before. Every time politicians float ID cards, the public bristles. It is not that we are anarchists. It is that it is not very British to have to flash your papers just to go about your day. The Second World War gave us reason enough, but the peace that followed gave us reason to chuck them in the bin. Harry Willcock proved the point when he refused to show his card and dragged the whole business into court.

To be fair, let us give Starmer the benefit of the doubt. He probably knows how un-British the whole idea sounds. That is why he dresses it up carefully. Think of it like a tool in the shed. You do not lug it around everywhere, you only fetch it when you need it. He is right in this sense: you will not need an ID to go to the shops, to the pub, or about your daily life. It is meant for official checks, for work, for renting, for proving who you are when it matters.

But the warning stands. If Starmer or any future politician tries to move the goalposts, to turn this into a daily burden, they will find something waiting for them: a lot of Harry Willcocks ready to say, “enough is enough.”