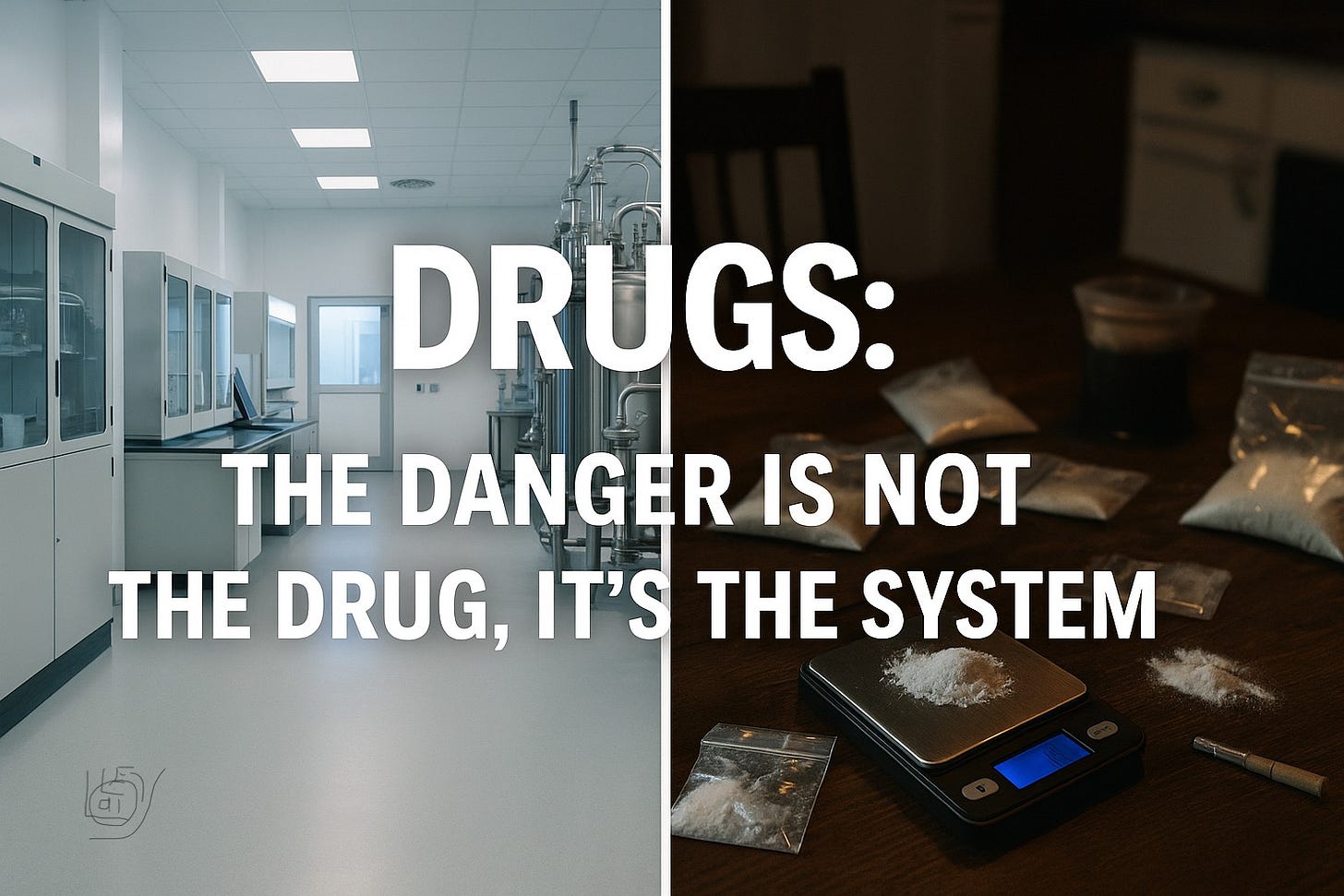

Part 6 of 7: Poisoned by Design Why Street Drugs Are Dangerous Because of Prohibition, Not Purity

If you were designing a system to maximise risk, unpredictability and health damage, you would design precisely the system we currently have.

In Part 5, The System Does Not Look Back, we stripped away the idea that drug markets are ignored because the police approve of them. They are ignored because they are quiet. They avoid noise, visibility and therefore scrutiny. A market that does not cause panic rarely triggers response.

Part 6 turns towards a darker, more neglected truth. If Part 5 exposed why the state averts its eyes, Part 6 explains what that blindness creates: a supply chain built to harm. Not by intention. By design.

Because street drugs in Britain are not dangerous because of chemistry.

They are dangerous because everything around the chemistry has been criminalised.

THE CONTAMINATION PROBLEM: A MARKET THAT CANNOT STAY CLEAN

In a regulated industry, contamination is a scandal. In the illegal drug economy, contamination is business as usual.

Most drugs sold on British streets contain whatever cheap, white powder was nearest to hand. Glucose. Caffeine. Paracetamol. Powdered anaesthetics. Veterinary dewormers. Chalk dust. Brick dust. Pills scraped off a chopping board that doubled as a dinner surface that same morning.

Medical toxicology departments see substances that would fail even the most basic safety audit. Emergency clinicians treat reactions that have nothing to do with the drug a user thought they were taking. Because what people buy is not cocaine, heroin or MDMA. It is a chemical lottery.

Purity is not what kills.

Uncertainty is.

WHY CUTTING HAPPENS: ECONOMICS, NOT EVIL

Dealers do not adulterate drugs out of malice. They do it because the illegal market rewards it.

Every gram stretched with filler increases the margin.

Every dilution keeps the business open one more day.

Every added substance disguises inconsistency in the upstream supply.

In a legal system, there would be counterweights: inspectors, liability, recalls, standards. In an illegal one, none exist. Harm is absorbed by the user, never the supplier. Overdoses do not reduce sales. A dead customer is replaced instantly.

The problem is not cruelty.

The problem is profit in the absence of oversight.

THE WEALTH–PURITY GAP: TWO MARKETS, TWO RISKS

There is a class divide in the British drug landscape that few politicians dare acknowledge.

At the top end of the market, affluent professionals access relatively consistent cocaine through small, stable networks. Not risk-free, but far removed from the filth circulating at street level.

At the bottom end, purity collapses and toxicity accelerates. Heroin users, crack smokers and vulnerable poly-drug users buy what they can afford, not what is safe. They are not operating in a marketplace. They are operating in a rationing system.

This creates two realities:

One group treats drugs as an accessory to nightlife.

Another uses them to cope with trauma, instability and pain.

The first group receives product that is merely risky.

The second receives product that is often lethal.

Purity maps onto privilege.

Risk maps onto poverty.

THE PHARMACEUTICAL PARADOX: THE SAME DRUG, TWO DIFFERENT WORLDS

Heroin, under its medical name diamorphine, is still used in British hospitals. In that controlled environment the addiction risk is real but manageable. Doses are measured. Duration is limited. The quality is exact. Patients taper off under supervision.

Compare that with street heroin, where the strength can vary by a factor of ten and the cutting agents can include anything from paracetamol to benzodiazepines to fentanyl analogues.

The molecule is the same.

The system is different.

And the system is what generates the harm.

THE HOSPITALITY PARADOX: HOW PUB CHAINS OUTPERFORM THE CRIMINAL MARKET

This is not a policy proposal. Nor is it a suggestion that Wetherspoons or Mitchells & Butlers have any intention of entering the regulated narcotics trade. It is a thought experiment, nothing more.

These companies already retail two of the most harmful drugs in the country: alcohol and tobacco. They do it under licence, under regulation, with compliance officers, CCTV, staff training, age verification, intoxication management and a duty of care. They already operate Britain’s largest drug distribution networks. We simply choose not to call them that.

Now imagine, theoretically, that cocaine or heroin were manufactured to pharmaceutical standards and distributed through those same trusted retail channels.

No kitchen-table chemistry.

No chalk dust.

No guesswork.

No contamination.

Just regulated production and competent distribution.

It would eliminate the entire cutting-agent economy overnight.

It would slash overdoses.

It would make the drug itself the only variable, not the toxic obstacles added along the way.

It is provocative but true:

If Wetherspoons sold heroin, the product would be safer than anything sold on the streets today.

Not morally safer.

Not socially safer.

But chemically, medically, and predictably safer.

Because the danger is not the heroin.

The danger is the criminal supply chain we force it into.

THE PURITY PARADOX: A QUIET CASE STUDY

A friend of mine once moved in circles where pharmaceutical-grade cocaine occasionally appeared. Not the brittle, bulked-out substance Britain knows as cocaine today, but clean, laboratory-standard material of the kind used in medical research.

He used it heavily for a period. When he stopped, he stopped. No collapse. No visible damage. No lingering dysfunction. Unless he chose to tell you about that chapter, you would never guess he had been a prolific Class A user.

The lesson is not that cocaine is safe.

The lesson is that the supply chain determines the harm.

We demand purity in alcohol.

We demand purity in tobacco.

We demand purity in every over-the-counter medicine.

Yet for the people most at risk, the ones with the hardest lives and the least power, we tolerate a system of supply that would be illegal in any other sector.

If our illegal drugs were as clean as our legal ones, the public health landscape would change overnight.

Purity is not indulgence.

Purity is harm reduction.

THE “GATEWAY TO ALCOHOL” IRONY

There is a cultural blind spot at work.

The idea that heroin is somehow a gateway drug collapses under scrutiny. By the time anyone touches heroin, alcohol has usually been part of their life for a decade or more. If Britain has a gateway drug, it is the legal one we celebrate.

Hospitals absorb alcohol’s violence and harm.

A&E departments drown in it.

Police logs record its nightly aftermath.

Families fracture under it.

The economy loses billions to it.

Heroin is devastating, yes, but alcohol outperforms it on almost every measure of societal harm.

Heroin is not a gateway to alcohol.

Alcohol is the gateway to everything else.

We simply refuse to describe it that way because alcohol is ours.

WHY PROHIBITION GUARANTEES DANGEROUS DRUGS

This is the central truth of Part 6.

Illegal drugs are dangerous because every mechanism capable of making them safe is illegal.

No testing.

No regulation.

No inspection.

No liability.

No product standards.

No quality control.

No recalls.

No dosing guidance.

No medical oversight.

If you were designing a system to maximise risk, unpredictability and health damage, you would design precisely the system we currently have.

The molecule is rarely the killer.

The prohibition economy is.

COMING UP NEXT: PART 7 — THE PUBLIC WANTS DRAMA, THE POLICE WANT PEACE

In Part 7 we turn to the great cultural misunderstanding at the heart of the British drug debate. Why the public still believes in the noisy, cinematic version of the drug war. Why politicians feed that imagination. Why the quiet markets we have described in Parts 4, 5 and 6 continue to thrive precisely because nobody wants to look directly at them.

Part 7 is where perception, politics and reality collide.