Rachel’s Budget, and the Different Ways Labour Is Trying to Save Itself

Reeves may be right on the arithmetic but does Labour understands how close to the edge many lives now sit.

Rachel Reeves delivered her Budget as an accountant would. Balanced, careful, meticulously boxed and labelled. It was designed to look serious. It was designed to prove Labour had grown up. It was designed to calm markets, soothe institutions and quiet the old accusations of fiscal chaos. In that narrow sense, it worked. The spreadsheets added up. The language was controlled. The briefings were disciplined.

But politics is not lived in spreadsheets. It is lived in kitchens, on buses, in broken lifts, in tired pay packets and in conversations that start with “I cannot keep up any more”. And it is here that the Budget begins to look fragile.

Reeves built a structure that helps those at the bottom, targets those at the top, and quietly loads weight onto those in the middle. The poorest gain support, and that matters morally. The wealthiest can afford to absorb what is being taken and were never likely to vote Labour anyway. But the poorest, in truth, do not vote in large numbers either.

This is where the logic begins to unravel.

If the poorest do not reliably vote, and the wealthiest were never going to, why construct a settlement that protects one group and punishes another, while leaning hardest on those who actually decide elections?

The answer is not economic. It is political.

Labour’s modern membership is overwhelmingly middle class, professional, and culturally radical in ways the wider country is not. It is wired for opposition, not government. It feels morally validated by redistribution, even when it does not bear the cost itself. This Budget flatters that audience. It reassures the membership that Labour still “means something”. It sends signals internally, not externally.

To satisfy that internal audience, Reeves has increased the load on the people who do vote Labour. The clerks, the skilled workers, the supervisors, the technicians, the office managers, the people who do not feel rich and are not protected as poor. This is where the pressure lands. Not in theory, but in lived reality.

Freezing tax thresholds does not look like a tax rise, but it functions like one. Pension changes do not look dramatic, but they nibble. Allowances shrink quietly. Responsibilities rise steadily. There is no single headline punishment, just a slow tightening that is felt every month.

In the West Midlands this is not abstract. It is visible on Coventry buses where workers count coins for fares. It is heard in Walsall cafes where mortgage renewals are discussed in low voices. It sits silently in Dudley industrial estates where firms survive but do not invest. It is in Wolverhampton terraces where families work full time and still have nothing left at the end of the week. This region is neither rich nor destitute. It is precisely the kind of place that feels every “technical adjustment” as a direct hit.

So the political structure now looks like this.

You help those who rarely vote.

You tax those who never would.

And you squeeze the people who put you in power.

That is not social justice. That is strategic risk.

Which leads to a question that deserves to be asked plainly.

Why do this?

Why design a Budget that secures applause in the party but builds resentment in the country? Why reward a membership that does not decide elections, while testing the patience of voters who do? Why choose internal reassurance over external consent?

This is not a question of compassion. It is a question of competence.

And this is where Shabana Mahmood matters.

Not as a personality, and not as a headline, but as a correction.

She has rejected the old fiction that border control belongs to the political right. She treats it as what it is, a basic duty of a functioning state. If a government cannot control entry, cannot enforce its own rules, cannot say what does and does not work, then it cannot be trusted with anything else either.

She is not shifting Labour “right”. She is pulling it back towards something more serious. The belief that enforcement is not cruelty. That boundaries are not bigotry. That a state must function before it can be compassionate.

This is not a cultural turn. It is a governing instinct.

And this is how she is trying to save Labour.

She has moved Labour’s position on immigration and asylum enforcement in a direction that made large parts of her own party uncomfortable. Faster removals. Clearer rules. Firmer language about who can stay and who cannot. Not wrapped in seminars. Not softened for internal audiences.

She framed it in the language of control.

She has been punished for that internally. Her approval among party members fell after tightening enforcement. Not because it failed, but because it worked. Not because it was cruel, but because it was clear.

She is trying to rescue Labour by reintroducing something unfashionable inside the party, respect for rules, respect for enforcement, respect for the idea that a government that will not act is a government that will not be believed.

There is something distinctly West Midlands in that instinct. It comes from places where state failure is not a talking point but a lived experience. Where housing strain, illegal working, community tension and pressure on services are felt in real time. She speaks from that reality, not above it.

This is not a moral pivot.

It is an authority pivot.

And this is the strategic split now sitting inside Labour.

Reeves represents the belief that Labour can survive by proving it is responsible enough. Mahmood represents the belief that Labour can survive by proving it is tough enough.

One speaks to markets and membership.

The other speaks to boundaries and belief.

They are both trying to save the same party.

They are both responding to the same fear. That Labour looks like a movement without edge. A government without grip. A party more comfortable in opposition than command.

Reeves tried to fix that with numbers. Mahmood tries to fix it with authority.

The question is whether either approach works.

Because the real danger for Labour is not attack. It is isolation. It is becoming legible only to itself. It is confusing conference applause for national consent. It is sounding serious while lacking authority.

Reeves may be right on the arithmetic. Mahmood may be right on the instincts. But neither can substitute for something harder, which is whether the country believes Labour understands how close to the edge many lives now sit.

This is not really a story about two women. It is a story about two survival strategies.

One stabilises.

One confronts.

One comforts the party.

One unsettles it.

Both are trying to save Labour.

And the most honest answer, for now, is that neither looks certain to succeed.

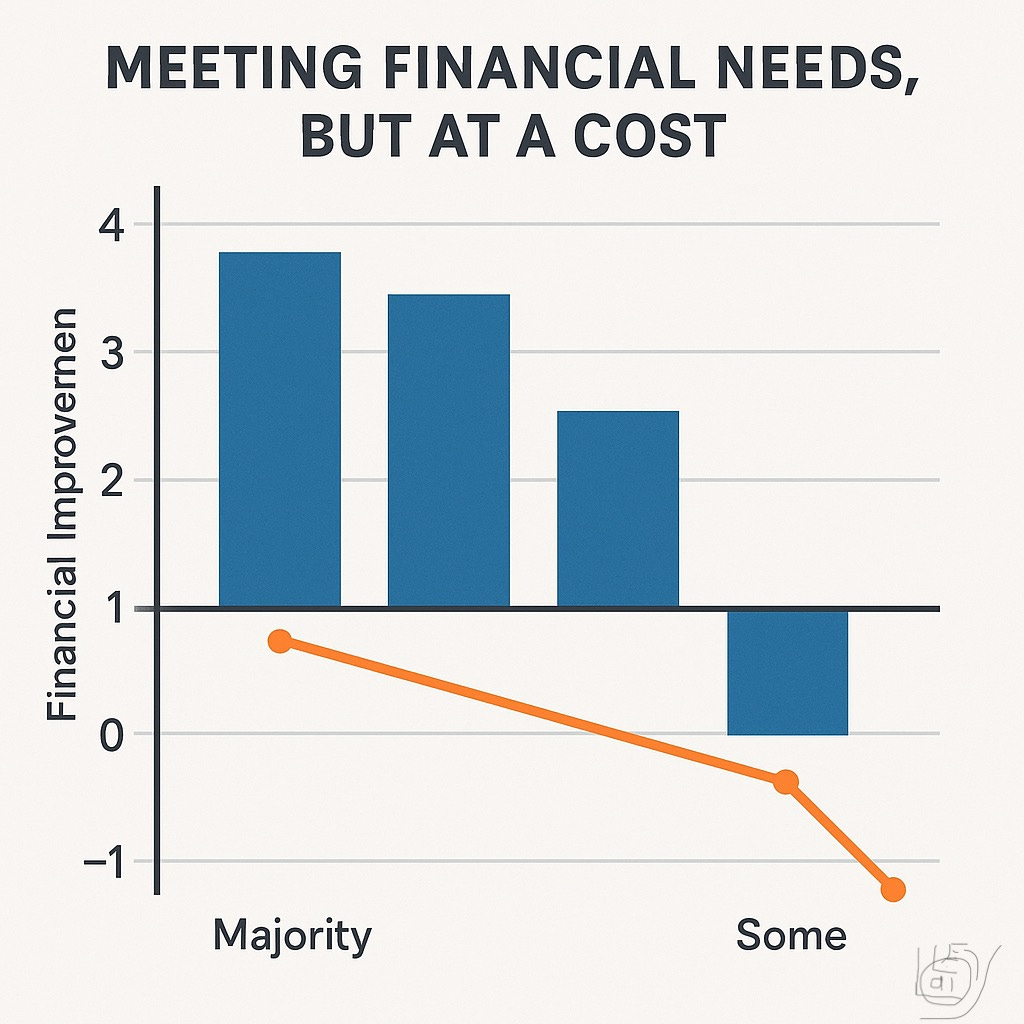

🤗 ps - if you was wondering what the graph at the top is all about - honestly not a lot, as is so often the case. It could mean this, it could mean that, - but ket’s face it it’s just rubbish really. But I hope you enjoyed it anyway.