Reform, Granny Dumping, and the Care Home Trap Waiting to Snap

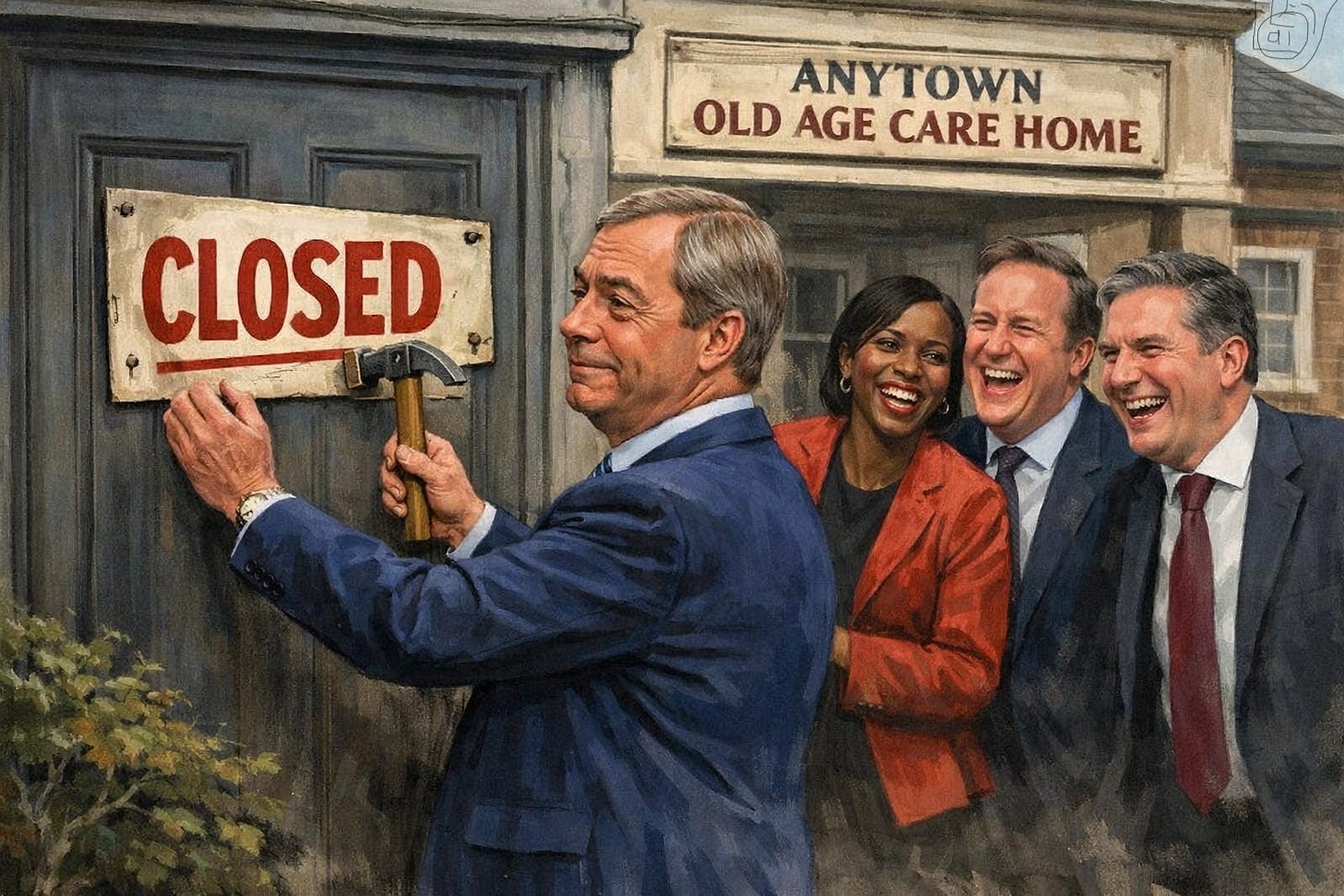

When a Reform-led council proposes closing one of the last remaining council homes, it looks like betrayal. The public do not see commissioning models or historical context.

I spotted an article claiming that Reform councils were “dumping grannies” by closing care homes. My first reaction was not outrage, but doubt. Could that really be true, I wondered. Are there even any council care homes left to close?

So I dug deeper.

What I found is more interesting, and more dangerous for Reform, than the headline suggests. Because while the charge is emotionally potent, the underlying reality exposes something far bigger: a half-century retreat from municipal care that predates Reform entirely. And yet, paradoxically, it is Reform who may end up wearing the blame.

This is what happens when a party moves from protest to power. The slogans survive. The systems do not.

Power changes the weather

Reform UK have shown a remarkable intuitive grasp of modern media. They understand outrage cycles, attention economics, and how to dominate the conversation with simple, declarative claims. They are agile, combative, and instinctively tuned to public frustration.

But power changes the weather.

Once you run councils, you inherit not just offices and budgets, but the accumulated consequences of decisions taken decades earlier. Adult social care is where that inheritance is most toxic, because it sits at the intersection of money, morality, and mortality.

It is also where Reform are most exposed.

What councils used to do, and quietly stopped doing

In the early 1970s, council-run care homes were not an anomaly. They were normal. Municipal homes for older people existed in every town and city, often modest, sometimes austere, but publicly owned, publicly staffed, and locally accountable.

In 1974, England had around 105,000 places in local authority homes for the elderly. That figure matters, because it anchors the scale of what has since disappeared.

Today, England has fewer than 8,000 council-run care beds, representing under 2% of total provision. Adjusted for population growth, that is a collapse of around 94% in direct public capacity.

This did not happen overnight, and it did not happen under one party. It happened gradually, under Labour, Conservative, and coalition governments alike. Councils sold homes, closed homes, or transferred them to private providers. Capital investment dried up. The skills of running residential estates withered. Commissioning replaced provision.

By the time Reform arrived, the municipal care home was already an endangered species.

The West Midlands, a case study in retreat

Nowhere illustrates this better than the former West Midlands County area: Birmingham, Coventry, Dudley, Sandwell, Solihull, Walsall, and Wolverhampton.

In the 1970s, this metropolitan area, with a population of around 2.6 million, likely had roughly 5,800 council-run care beds, spread across perhaps 180 to 200 council homes. That was the infrastructure of care as it then existed.

Today, with a population closer to 3 million, council-run provision has shrunk to perhaps 400 beds across a handful of homes. Per head, that is a collapse of more than 90%.

This is not a Reform innovation. It is the long tail of a policy consensus that decided councils should stop doing things and start buying things instead.

So when people ask, “how many pensioners have been dumped since the 1970s”, the honest answer is uncomfortable. On any given day, tens of thousands fewer older people are being cared for in publicly run homes than would once have been the case. Over fifty years, that absence has touched millions of lives, quietly, incrementally, without a single moment of reckoning.

Why Reform still get caught

Here is the political trap Reform are walking into.

Reform campaign as the party of common sense, protection, and “looking after our own”. That language implies visible, tangible care. It implies solidity. It implies presence.

When a Reform-led council proposes closing one of the last remaining council homes, even if residents are re-provided for elsewhere, it looks like betrayal. The public do not see commissioning models or historical context. They see buildings closing. They see headlines. They see “granny dumping”.

And Reform face something else the old parties no longer do: an aggressive media ecosystem actively looking to trip them up. They are no longer punching up. They are being watched from above.

In opposition, Reform could blame “the system”. In power, they are the system.

The three answers Reform can give, and why all are dangerous

Reform have three responses available to them.

The first is to say, “this was broken before we arrived”. That is true, but it sounds like excuse-making, and it cuts against their claim to competence.

The second is to say, “we cannot afford council-run care”. That places them squarely in the austerity tradition they claim to oppose.

The third is to say, “we are commissioning instead”. That is precisely the model that hollowed out public provision in the first place.

None of these answers satisfy the promise Reform made to voters.

Which leads to the harder question they cannot dodge.

Why did councils lose the capacity to care?

This is the question no major party has seriously confronted for a generation.

Councils once built and ran care homes as a matter of course. It was not rocket science. It required land, capital, staff, and standards. Over time, that capacity was allowed to die. Development teams were dismantled. Operational leadership drained away. The commissioning mindset replaced the municipal one.

Today, many councils genuinely lack the skills to build and run residential care at scale. Not because it is impossible, but because they stopped doing it.

That is the real scandal, and it belongs to everyone.

A moment of choice, not just for Reform

This is where Reform’s future is quietly being decided.

If they simply manage decline, they will be judged as hypocrites. If they blame officers or legacy systems, they will look weak. If they lean into culture wars while presiding over visible service retreat, they will be torn apart by the same media logic they once mastered.

But there is another path.

If Reform genuinely believe in looking after “our own”, adult social care is where that belief must be tested. Not in slogans, but in bricks, staff, and services. Rebuilding municipal care would be hard. It would take time, money, and political courage. It would also be wildly popular.

The irony is sharp. The party most likely to be accused of dumping pensioners may be the only one with the political freedom to rebuild public care, if it chooses to.

The question is whether Reform want to govern, or just to win arguments.

Power, once you have it, is always more complex than it looks from the outside.