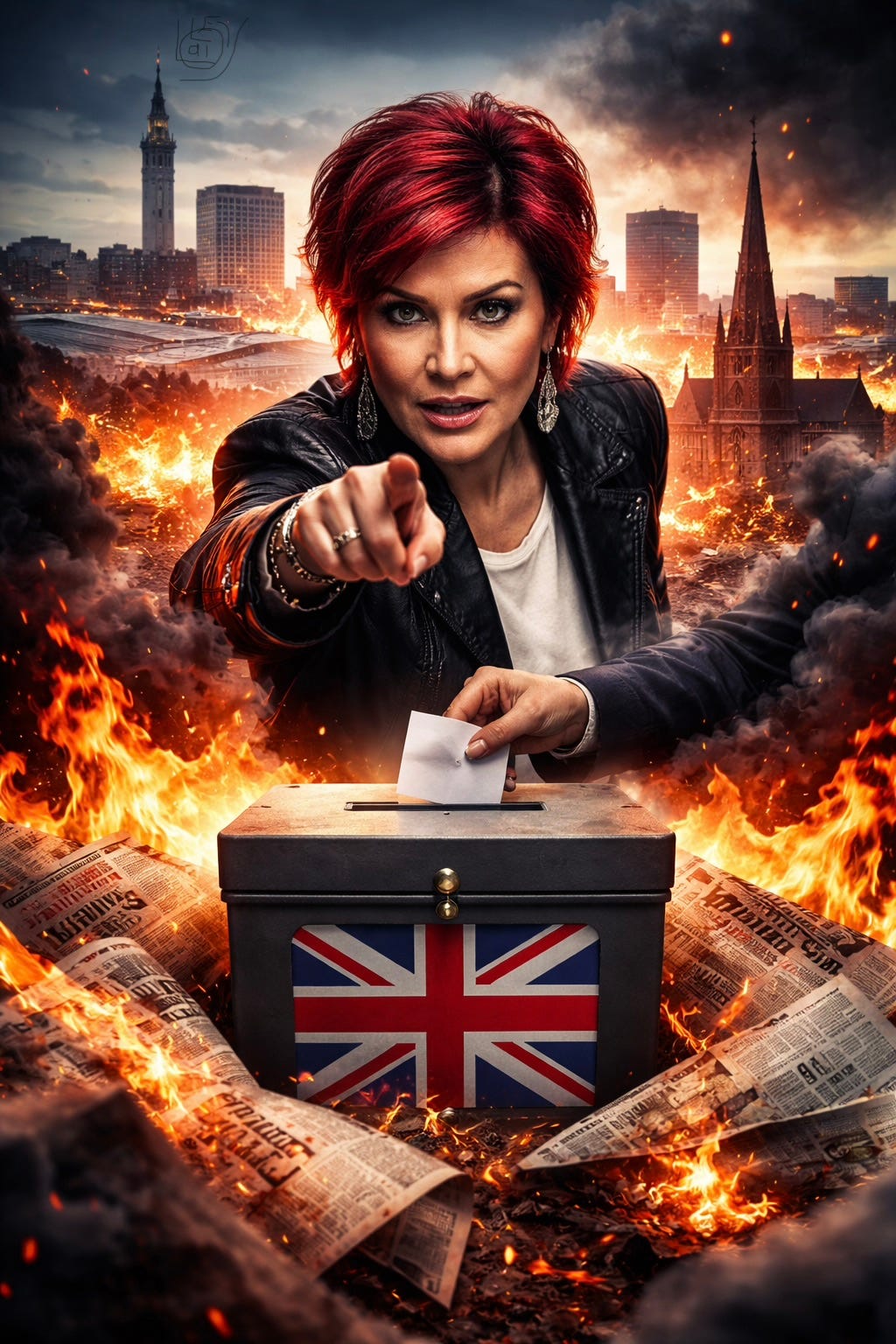

Sharon Osbourne, democracy, and a moment that matters

Can a man with a serious and controversial past, widely perceived, rightly or wrongly, by many as having links to terrorism or extremist violence, stand for office with a realistic chance of winning?

In recent days, Sharon Osbourne has suggested she may intervene directly in a Birmingham local election. Her remarks followed reports that a man with a serious and controversial past, widely perceived by many, rightly or wrongly, as having links to terrorism or extremist violence, could stand for office with a realistic chance of winning.

That alone was enough to cause a stir.

What followed was predictable. Media amplification. Political parties circling. A rush to frame the episode as either celebrity grandstanding or opportunistic point-scoring. But that framing misses something important.

This was not just about Sharon Osbourne.

It was about a line many British citizens, across backgrounds and political traditions, feel instinctively uncomfortable seeing crossed. The discomfort is not marginal and it is not confined to one community. It includes people of all heritages, including British Muslims who understand acutely the damage caused when extremist associations are left unexamined and then quietly normalised.

That unease is real. And it is widespread.

This is why the moment matters.

If Osbourne were to stand and lose, particularly to the candidate she objects to, the outcome would not be treated as a routine local result. It would be read nationally as a cultural rupture, confirmation for some that democratic safeguards are failing to keep pace with public consent.

If she were to stand and win, she would do something quite different. She would neutralise a volatile issue through the ballot box itself, absorbing the impact democratically rather than inflaming it.

Either way, this is not a neutral intervention.

Where this started, and who moved first

It is worth being precise about how this unfolded.

Sharon Osbourne did not emerge as part of a choreographed recruitment drive. Her comments arose from a specific and widely reported prospect, one that many people found disturbing long before she spoke.

The response from the Conservative Party came later, and frankly, it was inevitable. When a globally recognisable figure voices concern that aligns with an existing political fault line, parties will move quickly. Of course they would welcome her as a candidate. Any party would.

But opportunism should not be mistaken for authorship.

There is no evidence that Osbourne was briefed, stage-managed, or deployed. If anything, the pattern looks reversed. A celebrity reacts viscerally to something she finds alarming, and political actors scramble to harness the energy that follows.

That distinction matters.

Because what sits underneath this episode is not party advantage but a deeper anxiety. A fear that democratic legitimacy is being stretched beyond what many citizens are prepared to tolerate. Not because they reject democracy, but because they worry about what happens when moral scrutiny itself becomes taboo.

Distance, presence, and the lazy question of where councillors live

Once the initial shock subsides, the practical question inevitably follows. Could Sharon Osbourne realistically serve as a councillor?

Birmingham’s own history suggests this is the wrong place to start.

The city has previously been served by senior civic figures who lived well outside its boundaries, including a Lord Mayor who lived in Banbury. Distance did not prevent service. Commitment did the work. Years later, in a confidential conversation, his driver described the sheer grind of travelling backwards and forwards between Banbury and Birmingham. It was not glamorous. But the city was served.

When I served as a councillor myself, I never lived closer than ten miles from the ward I represented in Castle Vale. I lived on the south side of the city, travelled constantly, and delivered what I believe was serious, committed representation.

Distance is not the issue.

Absence is.

This is why comparisons are often drawn with Akhlaq Ahmed, councillor for Hall Green North. The problem there has never really been geography. Rumours about where he lives only gained traction because of something more corrosive. A weak attendance record, limited visibility, and a widespread perception among constituents that representation was thin.

People are remarkably forgiving about where you live if they can see results. They become suspicious only when nothing seems to move.

A different kind of councillor

Sharon Osbourne would not be a conventional councillor. Expecting her to be one misunderstands the role she could actually play.

She would not need to sit through every committee meeting to be effective. She could resource proper casework support, triage constituent issues through an office, and deploy her name selectively rather than constantly.

There are, in practice, three response speeds in public life.

There is the general public queue. Then there is the political queue. And then there is the rarely acknowledged third tier, where reputational gravity bends systems.

A letter from Councillor Sharon Osbourne would not sit unanswered in an inbox. It would be read. It would be escalated. It would be dealt with. Not because she is always right, but because visibility changes behaviour.

Used sparingly and sensibly, that leverage could deliver more for constituents than endless unanswered correspondence from an ordinary councillor.

Democracy, influence, and why this resonates

The final and perhaps most revealing aspect of this episode is what it tells us about democracy itself.

It is comforting to imagine that the rich, the famous, and the influential inhabit a different moral universe. In reality, they are often responding to the same anxieties as everyone else. Concerns about cohesion. About legitimacy. About whether the rules still reflect public consent.

Sharon Osbourne is wealthy. She is famous. She is influential. But in this moment, she is also reacting as a citizen who feels something important is going wrong and is choosing to engage through democratic means rather than commentary alone.

That should not be dismissed.

Democracy does not belong solely to party machines or career politicians. It belongs to those willing to test their convictions at the ballot box and accept the consequences.

If Sharon Osbourne stands, this will not just be about Birmingham. It will be about how Britain negotiates fear, legitimacy, celebrity, and civic responsibility at a moment of cultural tension.

Whether she wins or loses, the act itself will tell us something uncomfortable but necessary about the state of our democracy, and about who now feels compelled to defend it.