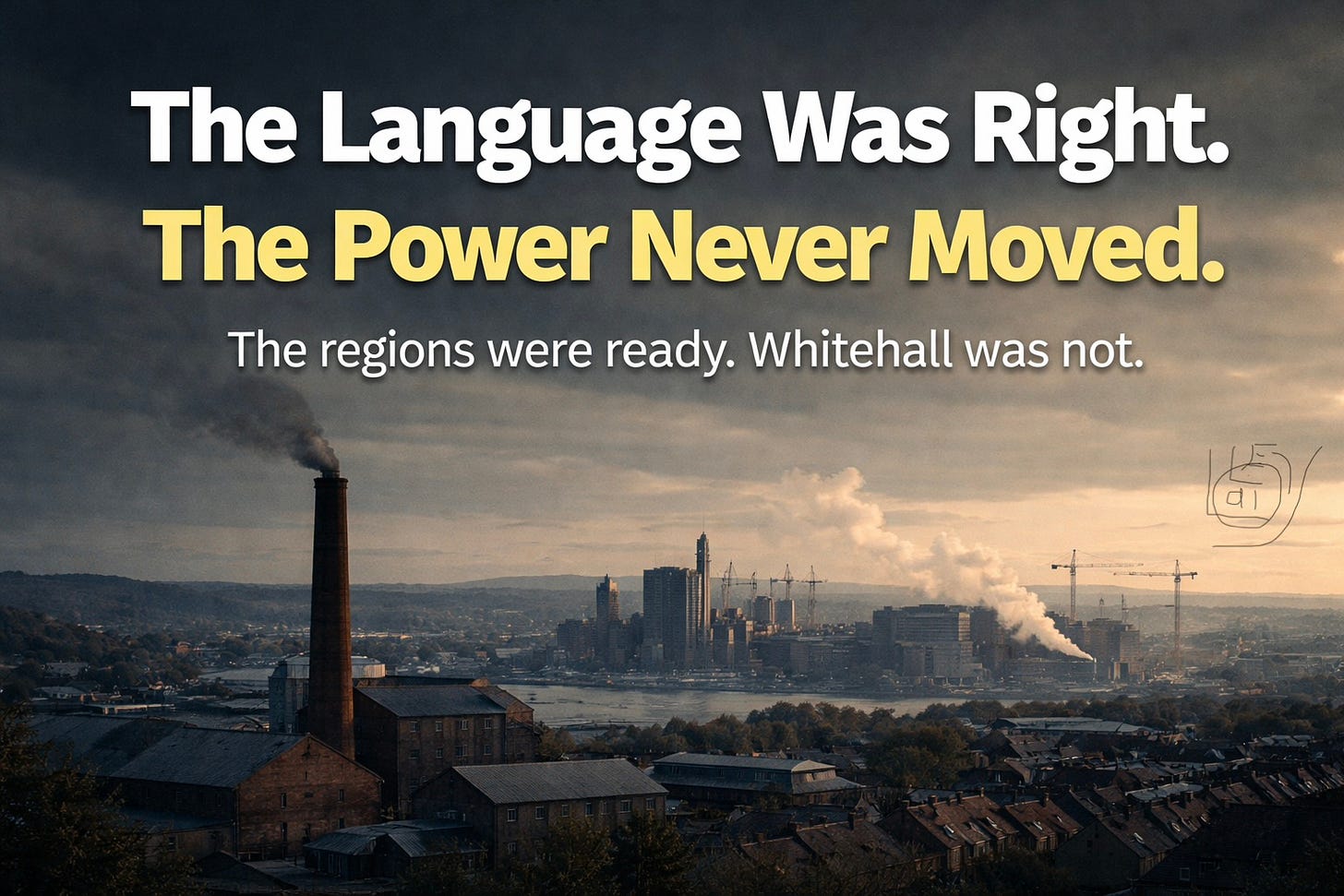

Six Months On, Labour’s Regional Promise Looks Hollow

It ticks all the boxes that modern industrial policy is expected to tick. But transfers no power from Whitehall to the regions.

When Labour’s Modern Industrial Strategy was published in June 2025, it arrived wrapped in the right language.

It spoke about place. It spoke about regions. It acknowledged, finally and openly, that the UK’s economy has been distorted by decades of over-centralisation, and that growth cannot continue to be channelled through London while the rest of the country is expected to make do with the leftovers.

For those of us in the Midlands, the North, and other long-overlooked regions, that recognition mattered. After years of being treated as delivery zones rather than economic actors, the language at least suggested that lessons had been learned.

Six months on, however, the question is no longer what the strategy says.

It is what it has changed.

And the uncomfortable truth is that very little has.

The Rhetoric Settled. The Reality Did Not Shift.

On the surface, the strategy reads fluently. It references place-based growth, regional capability, local institutions, and the importance of tailoring policy to different parts of the country. It ticks all the boxes that modern industrial policy is expected to tick.

But when you move beyond the prose and into the mechanics, a familiar pattern emerges. The centre still decides. The regions still deliver.

This is not a matter of tone or intent. It is structural.

Industrial strategy still originates in Whitehall. Strategic priorities are still set nationally. Funding still flows downward through centrally controlled programmes. Regions are still positioned as partners in delivery rather than authors of strategy.

The language has changed. The power has not.

Why Economists Have Seen This Coming

This gap between rhetoric and reality is not new, and it has been repeatedly identified by serious regional economists. Among them is popular B’ham Uni Professor Dave Bailey, whose work on industrial strategy and regional development has long warned against exactly this outcome.

Bailey’s argument is straightforward and consistently made. Industrial strategy only works when regions have real agency. That means control over investment priorities, long-term funding certainty, and the ability to align skills, infrastructure, and industry around local economic realities.

What does not work is coordination from the centre dressed up as decentralisation.

Industrial ecosystems are not abstract. They are geographically specific, historically layered, and institutionally embedded. They cannot be effectively managed through sector templates designed in London and applied uniformly across the country.

The new strategy acknowledges this in theory, but stops short of acting on it in practice.

The Midlands: Recognised, But Still Constrained

Nowhere is this contradiction clearer than in the Midlands.

On paper, the region should be central to any serious industrial strategy. Advanced manufacturing, automotive, engineering, logistics, clean energy, all are sectors in which the Midlands has real strength. The assets are tangible: deep supply chains, skilled labour, capable management, globally connected firms, universities, and decades of industrial know-how.

What the Midlands has never lacked is capability.

What it has lacked is authority.

Under the new strategy, Midlands institutions remain bound by nationally defined priorities, centrally controlled funding, and short-term competitive bidding. Long-term industrial renewal is broken into funding cycles that are too short for manufacturing. Skills provision remains misaligned with local employer demand. Infrastructure planning is fragmented across departments.

The region is trusted to deliver growth, but not trusted to design it.

A Case Study in Missed Opportunity

Take advanced manufacturing and automotive.

The Midlands already has Tier 1 and Tier 2 supply chains, experienced management teams, patient investors, export capacity, research and development capability, and a skilled workforce. These are not hypothetical advantages. They exist now.

What is missing is strategic control.

Investment decisions remain mediated through national programmes. Skills funding is shaped by generic frameworks. Infrastructure upgrades are subject to central prioritisation. The result is delay, friction, and underperformance relative to potential.

This is precisely the kind of ecosystem that Bailey has long argued cannot be governed effectively from the centre. It requires regional coordination with real authority, not distant oversight.

The Silence That Said Everything

Looking back to the strategy’s publication, one thing now stands out.

No one got particularly excited.

There were no ringing endorsements from regional leaders. No sense that a genuine shift of power had taken place. Figures such as Richard Parker and Birmingham City Council Leader John Cotton did not issue widely reported statements welcoming a breakthrough moment for the regions.

Regional bodies noted the strategy, aligned their paperwork to it, and carried on.

That quiet response now looks less like indifference and more like accuracy.

Regional leaders understand the difference between recognition and authority. They know when a strategy offers real leverage, and when it offers continuity expressed in better language. The absence of excitement was not a failure of communication. It was a sober reading of what was on offer.

We Have Everything Except the One Thing That Matters

This is the point at which the argument becomes unavoidable.

Across the Midlands, and across every region of this country, we already have what industrial renewal requires. We have expertise. We have competent management. We have serious investors willing to commit. We have skilled workforces and industrial ecosystems ready to grow.

What we do not have is control.

And this is not just a Midlands problem. Every region can tell the same story. That is why the disappointment runs so deep.

As a member of the Labour Party, this is not an easy conclusion to reach. Labour has always spoken the language of fairness, opportunity, and regional pride. I believed it was more in touch with the aspirations of the nation and its regions than this.

Instead, what we have been offered is something far more familiar. The language of decentralisation without the substance. The rhetoric of place without the transfer of power.

That is not just a policy failure. It feels like a slap in the face.

The regions are ready. The expertise is here. The investment is waiting.

What is missing is not capacity.

It is trust.

Typical.