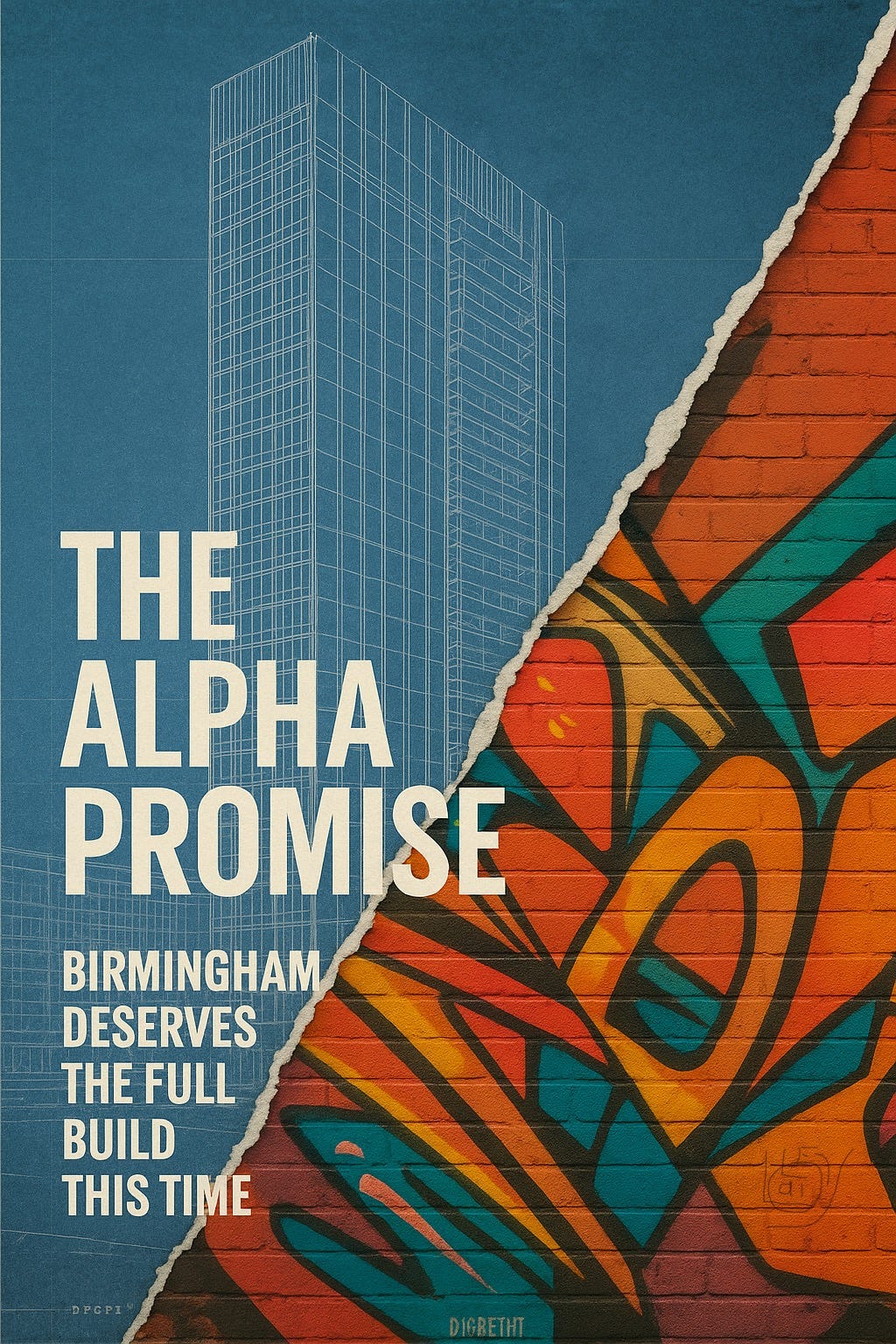

The Alpha Promise

Politicians queued to bless it. Journalists gushed. The public were told this was Birmingham’s metamorphosis from chimneys to cameras.

There is a real fizz around Digbeth at the moment. The cranes are up, the hard hats gleam, and the politicians smile as if they have just rediscovered Birmingham on a map. The words creative hub are being spoken with almost devotional zeal. BBC Midlands has returned, a few Peaky Blinders soundalikes are filming in old warehouses, and everyone from the Mayor to the man with a drone camera insists that this, finally, is our creative renaissance.

It is exciting stuff, but have we not heard this tune before?

Because Birmingham, for all its ingenuity and swagger, has a long record of falling in love with its own promise. If you trace the line back fifty years, you will find the original miracle foretold, the grand Paradise dream that produced Alpha Tower on Broad Street. It was going to change everything.

The Paradise That Never Was

Not the glossy Paradise of today opposite the Town Hall, but the first one, the scheme that was meant to make Birmingham the broadcasting capital of Britain.

Back in the late 1960s, when Associated Television, ATV, was at its swaggering peak, the company announced an audacious £15 million plan, close to half a billion pounds in today’s inflated funny money once you add in construction costs, consultancy creep and the usual civic embroidery. The project promised a modernist complex of television studios, shops, restaurants, a hotel and even a convention centre.

Alpha Tower was the flagship, a Seifert-designed slice of glass confidence that would anchor a whole media village and symbolise the city’s leap from smoke to signal.

The talk was of a broadcast powerhouse for the regions, pumping out colour television and film from the industrial heart of England. Politicians queued to bless it. Journalists gushed. The public were told this was Birmingham’s metamorphosis from chimneys to cameras.

What We Got

We got the tower, and a handsome one it remains, Grade II listed and recently refurbished, now full of accountants, lawyers and software firms. But the rest of the dream quietly dissolved.

The promised second tower never rose. The Paradise Centre’s hotel, shops and leisure spaces never materialised. The big convention hall was dropped when the council deemed it unaffordable. Even the grand entrance bridge, meant to connect Broad Street to the studios, went mostly unused.

By the early 1990s the cameras had gone. Central Television decamped to Gas Street and then to Nottingham. The old studios were flattened, and the land re-emerged as Arena Central, a tidy collection of offices, hotels and apartments.

The investors built what gave them the fastest return. The public lost the civic prize they were promised.

Alpha Tower stands today as Birmingham’s most elegant monument to what might have been.

The Alpha Promise and Cliff Sang It

For all the talk of Alpha Tower heralding a new broadcasting age, perhaps its truest legacy was musical, and not in a good way.

In 1973 the freshly minted tower shimmered across the skyline as Cliff Richard filmed Take Me High, his last and, if we are honest, least inspiring feature film.

It was supposed to showcase modern Birmingham, the canals reborn, the skyline sparkling, the new media quarter rising. Instead, we got Cliff in a hovercraft, crooning by Gas Street Basin and launching a gourmet burger bar.

At the time it was meant to symbolise progress, the same civic optimism that Alpha Tower embodied. But like the building, it became an emblem of the Alpha Promise, glossy, well-meaning, and completely disconnected from what Birmingham actually became.

Half a century on, the film feels like a time capsule from an era when the city truly believed it was on the brink of greatness, and somehow missed its cue.

Peaky Ironies and the Digbeth Now

Fifty years later, the city has another story to tell. This time it is Peaky Blinders, name-checked in every funding bid and media release. Yet, as everyone quietly knows, the early series were not even filmed here. The look and the legend were ours, but the work and the money happened elsewhere.

That is Birmingham all over. The ideas are born here, but the value is realised somewhere else.

To be fair, Digbeth today has already delivered more than its critics admit. New studios are open, creative businesses are moving in, and there is a genuine hum in the streets. People are making things again. There is life, art and a pulse.

But this is precisely why we must push harder now, not settle for another half job. Digbeth does not need to become Alpha Tower with better public relations. It deserves the full delivery, proper training pipelines, local ownership, affordable workspace, long-term jobs, and studios that stay open long after the ribbon has been cut.

The Luvvies and the Loops

Meanwhile a familiar troupe of arts administrators glide from project to project, fluent in the dialect of placemaking and co-creation. They hold beautifully catered meetings and commission public artworks that cost ten or twenty times what any sensible artisan would charge, every extra pound wrapped in phrases such as engagement outcomes and evaluation frameworks.

The welders, carpenters and painters see little of it. What was once craft becomes consultancy.

At the same time, Film Birmingham has slipped into silence. Whatever the internal reasons, the region has fallen behind in attracting real production work. Yet the West Midlands Combined Authority is investing heavily once again, promising a bold film and media future with the usual glossy reports, the usual smiling faces, and the compulsory nod to Peaky Blinders as creative patron saint.

It is a pattern we know by heart.

Big announcement.

Funding pot.

Launch party.

A few showreels and glowing reports.

Then the slow fade.

We heard it around Alpha Tower. We saw it with the first Paradise. We can feel it circling Digbeth.

This Time, Make It Stick

None of this is to pour cold water on Digbeth. Far from it. The district has what Broad Street never did, community, authenticity and a stubborn creative streak. It can become a thriving engine of industry and art. But to make it real, we need more than sentiment and selfies.

If public money is going in, the public must see tangible, lasting benefit. If developers are to profit, they must also deliver the cultural infrastructure they promise, in brick and beam, not in brochures.

This is where our politicians must lead. Not simply attend openings. Lead. The West Midlands needs a plainly written, legally nailed down model of creative delivery.

One that says, if studios are promised, studios are built first. If training is pledged, training is funded and run locally. If local makers are promised work, they get the contracts, not the same recycled consultancies from elsewhere.

That is what political creativity looks like. Not another ribbon cutting, but the courage to insist that promises stick.

Because Birmingham Deserves the Full Story

Birmingham does not need more optimism. It needs execution. It needs politicians who understand that leadership is not posing for photographs, it is locking delivery into law and budget.

So here is the challenge. Let us see the Alpha Promise finally honoured, half a century late. Let Digbeth deliver everything that Broad Street never did, the art, the industry, the jobs, and the pride.

The cranes are already up. The talent is here. The only thing missing is the political courage to finish the story.

Because this time, Birmingham deserves the credits to roll on a story that actually ends well.