The Party That Collapsed at Birth ?

Eventually ever party will dance with the devil.

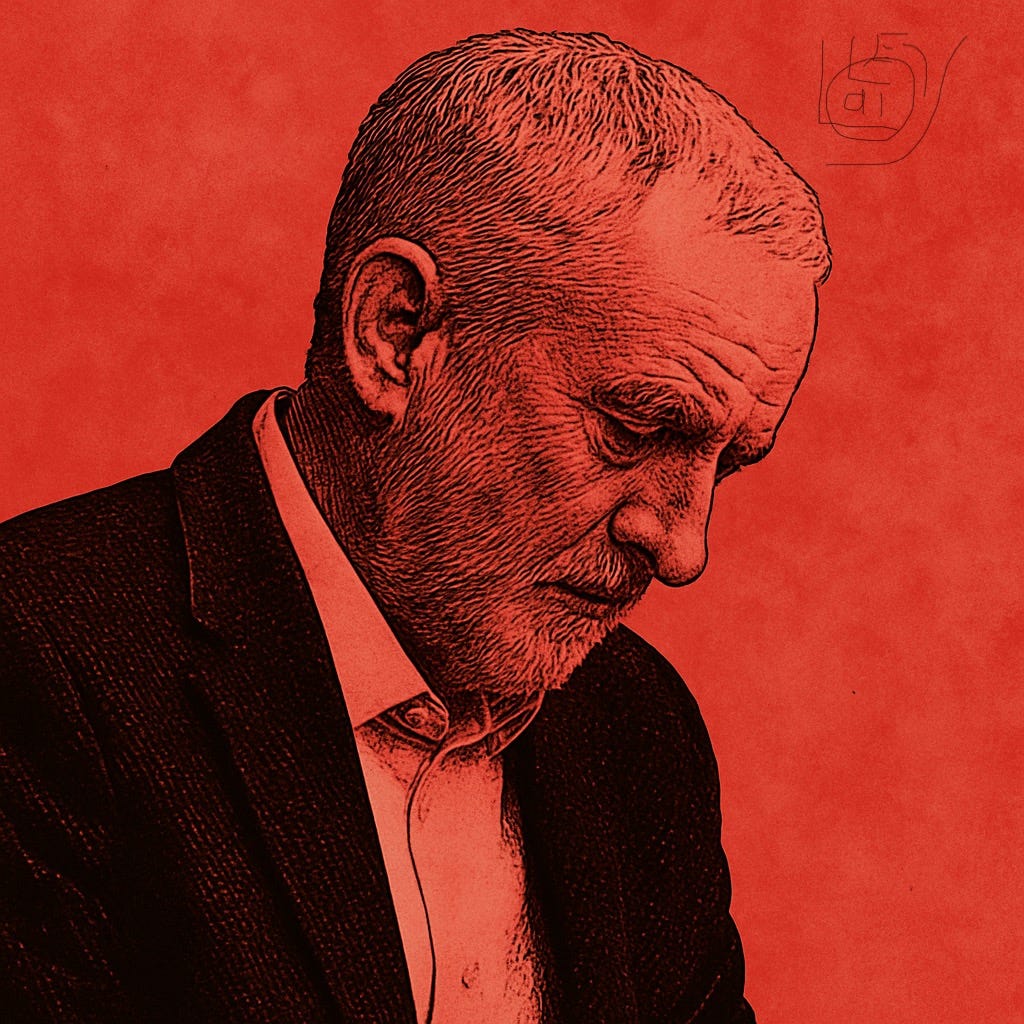

Jeremy Corbyn’s “Your Party” already looks doomed before it has even been launched. At the very moment one Left-wing project is imploding, another is trying to soar. Zack Polanski’s populist capture of the Green Party has filled it with noisy energy, but the echo of Corbyn hangs heavy: a leader adored by activists, mistrusted by voters, and destined to make every faction in British politics dance with a devil

.

A Stillbirth in Politics

Jeremy Corbyn’s latest project, provisionally titled Your Party, may go down as a record-breaker in British politics. Not for its success, but for its speed of implosion. Before it has even been formally launched, its supporters are already engaged in open warfare.

The new alliance brings together a clutch of “Gaza independents,” Zarah Sultana, and Corbyn himself. On paper, it looks like a bold new start for the anti-establishment Left. In practice, it is a marriage of convenience between factions that have almost nothing in common.

The Gaza independents were elected on a single issue: outrage at Labour’s stance on Palestine. They represent religiously conservative constituencies that are broadly unmoved by the cultural fixations of the Corbynite Left. They do not share enthusiasm for gender self-identification, trans rights, or the endless semantic battles over women’s spaces. Yet these are the obsessions of the Corbynite activist base, who treat “trans women are women” with the same reverence as “free Palestine.”

The clash was inevitable, and it has already come. One of the new MPs, Adnan Hussain, sparked fury simply by defending women’s rights and single-sex spaces. For the identitarian Left, this was a heresy too far. The spectacle of Corbyn’s allies hurling accusations of “transphobia” at their own side before the party has even filed paperwork is a fair warning of what lies ahead.

⸻

The Long Death of the CPGB

The Communist Party of Great Britain was founded in 1920 amid the aftershocks of the Russian Revolution. For decades it never broke through electorally but built influence through trade unions, intellectual journals, and anti-fascist campaigns. At its wartime peak, it had some 60,000 members.

Its downfall was slow and painful. The first great crack came in 1956, when Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech” revealed Stalin’s crimes and Soviet tanks rolled into Hungary. Thousands of members walked out. From then on, the party was riven by division: hardline Stalinists clung to Moscow, while younger Eurocommunists urged democratic reform.

By the 1980s the CPGB was at war with itself. The Eurocommunists captured its journals; the hardliners walked away to form the Communist Party of Britain. When the Soviet Union itself collapsed in 1991, the CPGB finally dissolved. After seventy years, it died not with a bang but a whimper.

Even a party propped up by global communism, with roots in unions and cultural life, could not survive permanent factional strife. Your Party, with none of that ballast, looks fragile indeed.

⸻

The SDP’s Brief Flame

The Social Democratic Party was born in 1981 out of Labour’s civil war. The “Gang of Four” — Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Bill Rodgers, and Shirley Williams — declared that Labour had swung too far left and founded a new centrist force.

At first, the SDP looked formidable. In alliance with the Liberals it polled well into the 30s, with by-election triumphs and a sense of real momentum. But the cruel arithmetic of Britain’s electoral system brought it down to earth. In the 1983 general election, the Alliance won 25% of the vote but only 23 seats.

The partnership staggered on, but by 1988 the majority of SDP members voted to merge with the Liberals and form the Liberal Democrats. David Owen refused, attempting to keep a “continuing SDP,” but it soon fizzled out. The whole experiment had lasted just seven years.

For all its flaws, the SDP had heavyweight leaders, millions of votes, and national recognition. Yet it still crumbled under pressure. If such a party couldn’t endure, what chance does Corbyn’s alliance of grievance politics have?

⸻

The Far-Right Carousel: NF and BNP

On the far-right, the cycle of rise and collapse is almost a tradition. The National Front emerged in 1967 as a merger of smaller fascist groups. In the 1970s it became notorious for racist marches and violent clashes with anti-fascists. For a time, it looked like the NF might break into the political mainstream, claiming to be Britain’s fourth party. But the violence, the thuggery, and the endless leadership feuds ensured it went nowhere electorally. By the early 1980s it had collapsed into splinters.

From one of those splinters came the British National Party. John Tyndall founded it in 1982, promising a more disciplined version of the far-right. For years it was marginal, but under Nick Griffin’s leadership it sought respectability. At its peak, the BNP won council seats, representation on the London Assembly, and in 2009 two MEPs. For a moment, it looked as though the BNP might secure a foothold in national politics.

It didn’t last. Internal corruption, financial mismanagement, and bitter rivalries dragged the party down. More importantly, the rise of UKIP offered a “respectable” anti-immigration alternative. BNP voters flocked to Nigel Farage, leaving the BNP a hollow shell. By the mid-2010s, it was dead in all but name.

Even the BNP, for all its corruption and extremism, at least managed to win elections before its implosion. Your Party may not even make it to that stage.

⸻

A New Devil in the Dance

The irony is that while Corbyn’s stillborn venture collapses under the weight of its contradictions, another force on the Left is striding forward with a different kind of populism. Zack Polanski’s takeover of the Green Party has been hailed as a victory for grassroots energy, but to many in Westminster he looks like a Corbyn rerun in green clothing.

Polanski has the membership at his back and a gift for media stunts, yet the electorate may be less forgiving once the press paints him as another hard-left ideologue. His eco-populism may thrill activists, but Labour fears he will bleed their progressive vote; the Conservatives and Reform relish him as a bogeyman; the Lib Dems see him as a poacher of their middle-class base; and even Greens in rural towns mutter that he is dragging them into a cultural war they never sought.

Already, the cracks are showing. Hours after his leadership victory, Polanski was hit with calls to sack his new deputy, Mothin Ali, after footage surfaced of Ali defending Hamas’s assault on Israel. In the video, Ali declared that all people had a right to “fight back against occupiers” and suggested Israel would use Hamas’s actions as a “pretext” to attack Gaza — remarks that risk alienating voters far beyond the activist base.

For Polanski, it is an early test of discipline, credibility, and judgement. Whether he reins in his deputy or stands by him will tell us much about the kind of leader he intends to be — and how quickly his own party may succumb to the familiar fate of Left-wing experiments that burn brightly, fracture, and collapse.

⸻

The Implosion Risk

Seen against this backdrop, Your Party looks weaker than any of them. The CPGB lasted seventy years before the weight of history crushed it. The SDP survived seven years, buoyed by millions of votes, before its contradictions broke it. The NF and BNP rose and fell in cycles of violence, splintering, and electoral irrelevance.

Corbyn’s project is different. It is already showing signs of collapse before it has a constitution, a name, or a coherent programme. Its leaders are pulling in different directions; its supporters are at each other’s throats over trans rights before they have agreed on a logo.

The Gaza independents cannot be expected to align with the cultural obsessions of Corbynite activists. Corbyn himself remains haunted by the antisemitism scandals of his leadership. Sultana has her own ambitions, already jarring with his. Nothing binds them together except Palestine solidarity, and that alone cannot hold a party.

⸻

Conclusion

British political history is littered with splinters. Some clung on for decades, others burned brightly then faded, and a few stagger on in reduced form. But all of them, even the most dysfunctional, at least lived long enough to fight elections and test their support.

Your Party may be remembered not as a splinter but as a stillbirth — the first political project of its scale to collapse before it was even born.

And Polanski? His Green insurgency may yet endure — but the first cracks are already visible. If Corbyn’s new venture risks collapsing before birth, Polanski must beware of a different danger: premature implosion.

At this rate, one project may be stillborn and the other miscarried. Either way, the dance with devils continues.