Thirteen Years That Means Six

A Midlands tragedy and the quiet dishonesty of British sentencing

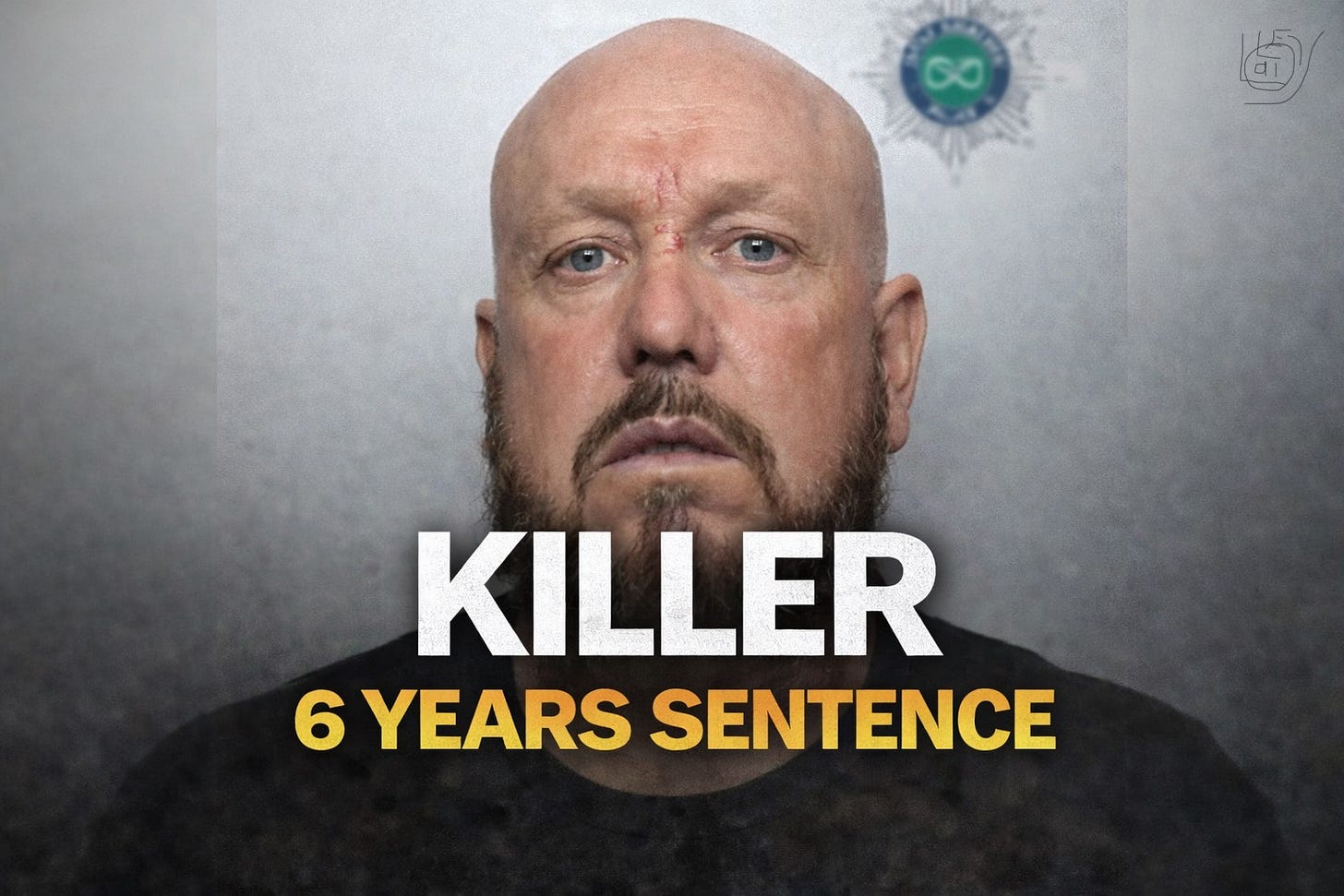

On a spring morning in the West Midlands, at Aston Wood Golf Club near Sutton Coldfield, Suzanne Cherry, a 62-year-old wife and mother, was walking across the fairway looking for her golf ball. She never made it home. A van driven at speed by John McDonald left the road and tore across the course as he fled police. McDonald was not an unlucky motorist having a bad day. He was at the centre of a rogue roofing operation that had been targeting homeowners, and he chose to try to escape rather than stop. The van struck Suzanne Cherry with catastrophic force. She died days later in hospital. This week, at a Midlands court, McDonald was sentenced to 13 years in prison. A Staffordshire Police spokeswoman said she hoped the sentence would bring the family some comfort. It was a humane sentiment. It also exposes a deeper problem in how sentencing is spoken about in this country.

Because the number that is spoken in court is not the punishment as it is actually lived.

The sentence the public hears, and the sentence the law applies

To most people, a 13-year sentence sounds like removal from society for a long time. It sounds serious. It sounds proportionate to the harm caused. That is the impression the system allows to stand.

In reality, this was a standard determinate sentence. Under the law of England and Wales, such sentences are automatically reduced by half. Release at the halfway point is not a concession, not a reward, and not a matter for discretion. It is built into the structure of sentencing itself.

This is not widely stated at the moment sentences are announced. Judges speak the headline figure. Release mechanics are left to be discovered later, if at all. The result is a persistent gap between public understanding and legal reality.

Why clarity is avoided

Judges will say they are required to state the headline sentence. Politicians will say release rules are a matter for statute. Police will say sentencing is not their role. Each is telling a partial truth.

What is avoided is plain language.

If sentences were expressed in terms of expected time in custody, public confidence would be tested immediately. The difference between the harm done and the consequence imposed would be impossible to ignore. So the system relies on convention and silence, allowing numbers to sound heavier than they are.

This is not a failure of intelligence on the part of the public. It is a failure of candour on the part of institutions.

Recklessness and moral equivalence

What makes this case especially difficult is the nature of the behaviour involved. This was not a momentary lapse. It was sustained, knowing, extreme recklessness. McDonald drove at speed through public space, mounted pavements, rammed police vehicles, and ultimately took a van onto a golf course where people were present, all to avoid accountability.

If someone fires a gun blindly into a crowded area and kills a stranger, the law does not comfort itself by noting the absence of specific intent. It recognises that choosing such conduct makes death foreseeable, and therefore culpable.

When the weapon is a vehicle, the law draws a sharper distinction. Intent is treated as decisive. Recklessness, however extreme, is downgraded. This distinction may satisfy legal doctrine, but it sits uneasily with public moral judgement.

Political design, not judicial accident

It is often said that sentencing is a matter for the courts. That is only partly true. Parliament created this framework. Parliament decided that most sentences should be automatically halved. Parliament expanded headline maximums while allowing time actually served to shrink. Parliament has repeatedly chosen capacity management over public protection.

If legislators wanted sentences for death caused by extreme recklessness to mean what they appear to mean, they could change the law. They have not. The reasons are familiar: cost, prison capacity, and political risk.

The result is a system that sounds tough while operating softly.

The academic influence behind the scenes

There is another influence rarely acknowledged in public debate. For decades, academic criminology has framed prison primarily as a social failure. Incapacitation has been treated as crude. Rehabilitation has been elevated above public protection. Victims have been discussed as outcomes rather than enduring absences.

This thinking has shaped guidelines, judicial training, and sentencing culture. It has produced a system highly attentive to the future prospects of offenders, and far less attentive to the permanence of loss suffered by those left behind.

Academics do not live with the consequences of their frameworks. Families do.

Sympathy without honesty

The police spokeswoman’s words were not cynical. They were institutional. Police forces have learned to speak the language of a system they operate within, offering sympathy while avoiding the mechanics of punishment.

But sympathy without clarity risks becoming a form of evasion. Comfort offered on the basis of a number that does not reflect reality cannot carry the weight it is asked to bear.

A simple test of honesty

There is a straightforward reform that would restore trust. Judges should be required to state sentences in terms of expected time in custody, alongside the headline figure. No euphemism. No convention. Just clarity.

The resistance to this proposal is revealing. It suggests an awareness that the system, if described plainly, would struggle to command public consent.

Not vengeance, but proportion

This is not a call for brutality. It is not bloodlust. It is not a rejection of mercy. It is a demand for moral proportion.

A society that cannot say, clearly and honestly, that those who behave like loaded weapons will be removed from circulation for a long time is not compassionate. It is negligent.

A Midlands story, with national meaning

This case happened in the Midlands, but the fault line it exposes runs through the entire justice system. Until sentences are spoken honestly, they will continue to comfort institutions more than they comfort those who have lost someone they loved.

That is not justice failing loudly. It is justice failing quietly, behind carefully chosen words.

Any right minded person who saw the original case reported, then the weaponised vehicle, then the fatal incident would conclude that 13 years was too short a sentence, but knowing that he will only serve half is an insult to society not alone to the families loss.