When the Shouting Stops: How Councillor Majid Mahmood Found His Voice and Then Lost It

Nolan - Measured against those standards, the council’s handling of this affair, and Mahmood’s personal response, falls short on nearly every count.

There was a time when Councillor Majid Mahmood was impossible to miss in Birmingham’s ongoing refuse wars. During the early weeks of the bin strike in March 2025, his social media feeds crackled with righteous indignation. He accused Unite the Union of intimidation at the depots, alleging that council staff and contractors were being bullied on the picket lines.

He was so incensed that he publicly quit Unite, the very union he had long supported. His resignation was splashed across Birmingham Live and amplified on social media: the cabinet member responsible for the city’s waste service had walked away from his union, saying he would not tolerate threats or abuse.

It was a dramatic move, and it fitted neatly with the council’s preferred narrative of law-abiding officers besieged by militant strikers.

Unite denied the claims outright. They said the depots were peaceful, that management were the real aggressors, and that the council was weaponising language to distract from a failing service. But Mahmood had made his stand. He had found his voice and used it loudly.

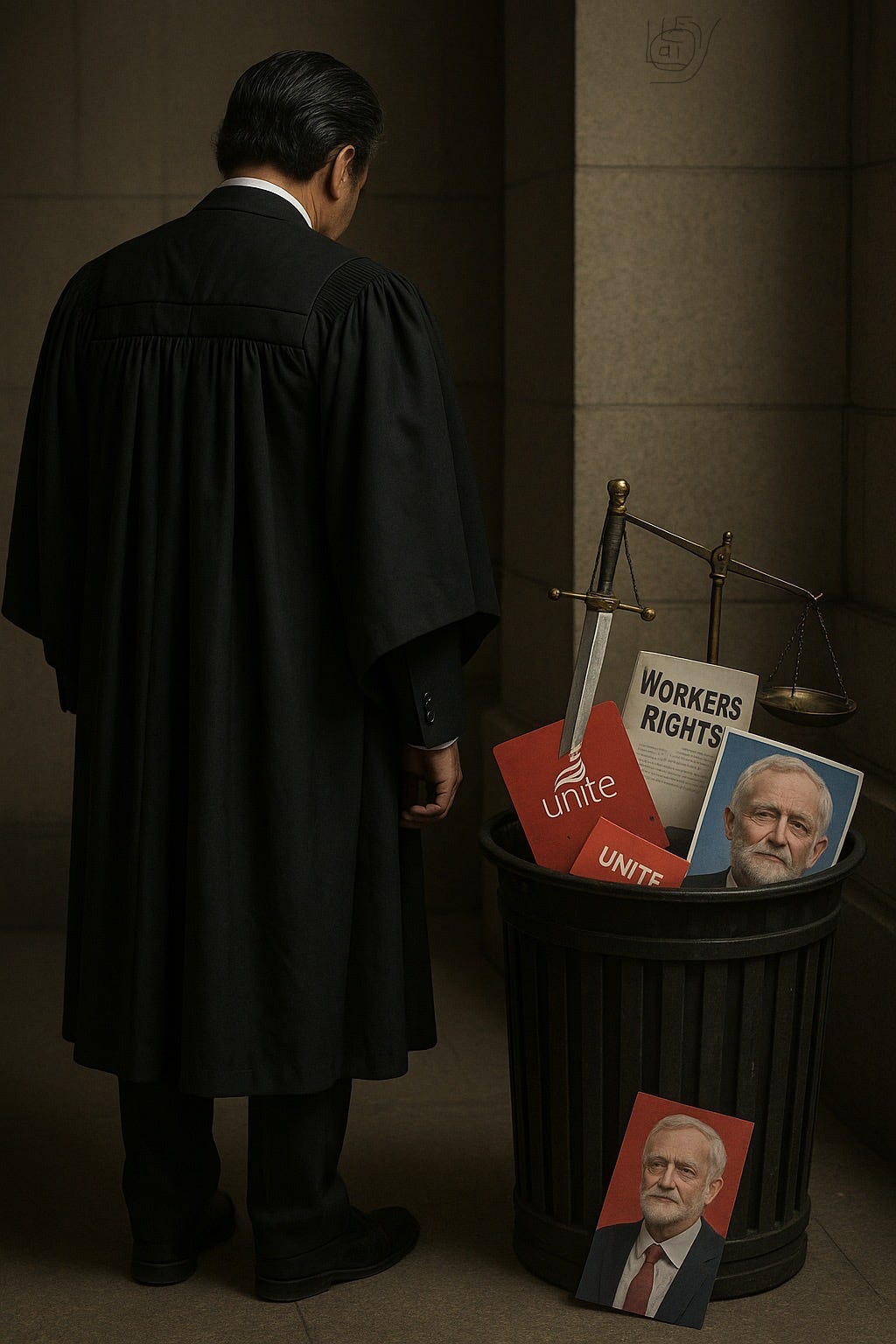

From Corbyn’s man to the council’s man

To understand why that matters, it helps to recall where Mahmood came from politically.

There was a time when he styled himself as Jeremy Corbyn’s man in Birmingham, the first among equals in the city’s Momentum wing, championing grassroots socialism and the rights of organised labour. Back then he was a fixture at rallies and meetings, positioning himself as one of the faithful guardians of Corbyn’s vision for a fairer, more transparent politics.

For a while he looked every inch the rising star of Birmingham’s left: bright, ambitious, grounded in community work and unashamedly pro-union.

That makes what follows so much harder to square.

A different silence

Seven months on from his anti-Unite outburst, Mahmood’s famous voice has fallen silent.

The same department, still mired in dispute, now faces fresh allegations of bullying, harassment and blacklisting, this time directed at agency workers employed through Job and Talent on the council’s contract.

A leaked video shows a manager telling agency staff that anyone who joins the picket line “will not be offered a permanent job by the council.” Those remarks, allegedly cleared with senior council officers, have triggered a new ballot for industrial action among the agency workers themselves.

In short, the so-called scabs once hired to break the strike are now threatening to strike against the council over mistreatment.

And where is Councillor Mahmood, the once-vocal champion of civility and fair play? Silent. No tweets, no Facebook updates, no press statements. The man who denounced union bullying has had nothing to say about bullying when it appears to come from his own organisation.

The duty to the law

When the video surfaced, Birmingham City Council announced it would immediately begin an investigation. That was on 14 October 2025.

By the end of the month, Unite said it had heard nothing. The three named managers were still in post, no investigator had been identified, and no terms of reference had been shared.

This is not what a lawful investigation looks like. The council’s duties under the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 and the Blacklists Regulations 2010 are unambiguous: any suggestion that workers were penalised or threatened for trade union activity must be examined thoroughly and transparently. Blacklisting is not an internal discipline issue; it is a statutory offence that can carry civil and criminal consequences.

A responsible authority would secure the evidence, suspend the officers concerned on neutral grounds, and appoint an independent investigator. Instead, Birmingham City Council made a public promise and then slipped into silence.

That silence matters. It sits within a portfolio headed by Councillor Majid Mahmood, a qualified solicitor and therefore an officer of the court. A lawyer’s first duty is to the rule of law, not to political convenience. When potential breaches of employment and public law duties occur under his watch, the public has every right to expect more than a holding statement and a closed door.

The Nolan principles

Public life in Britain is guided by seven principles set out by Lord Nolan in 1995: Selflessness, Integrity, Objectivity, Accountability, Openness, Honesty and Leadership.

Measured against those standards, the council’s handling of this affair, and Mahmood’s personal response, falls short on nearly every count.

Integrity demands that decisions are not influenced by personal or political advantage.

Accountability requires office-holders to answer for their decisions and submit to public scrutiny.

Openness insists that information be made available unless there are clear and lawful reasons to withhold it.

Yet when a serious allegation emerged, the council offered opacity instead of openness, evasion instead of accountability. Mahmood, as the political lead, had a duty to ensure these principles were upheld. His professional background as a solicitor makes that duty heavier still, for officers of the court are expected to embody honesty and integrity as a condition of their standing.

The Nolan principles are not optional extras of good behaviour; they are the ethical floor of public service. If those principles are ignored, governance itself begins to rot.

And in that context, one simple truth bears repeating: lawkeepers should not be lawbreakers.

If those entrusted to uphold the law, councillors, officers and solicitors alike, cannot meet the basic standards of transparency and fairness, then Birmingham’s crisis is not just one of rubbish and refuse but of moral decay.

Possible malfeasance

If council officials, or those acting under their authority, knowingly allowed threats of blacklisting to be made, that behaviour could stray into the common-law offence of misconduct in public office: the wilful neglect of duty by a public officer to the detriment of the public interest.

Even if no criminal element is ultimately proven, the perception that a local authority might downplay or conceal such conduct undermines trust in governance itself.

For a city already under government commissioners, that perception is corrosive. The integrity of Birmingham’s leadership, both political and professional, should reassure its residents that lessons have been learned. Instead, the waste service under Mahmood’s control has become a test case for how those lessons are being forgotten.

The moral vacuum

For Birmingham residents, this saga is no longer about missed collections or overflowing wheelie bins. It is about the corrosion of integrity in local governance.

Agency staff, many on precarious contracts, describe impossible workloads and whispered warnings. Unite says management used threats of blacklisting, while the council insists it has investigated and found no evidence.

Yet that claim of an investigation is itself troubling. The council announced an inquiry within days of the video appearing and then declared the matter closed almost as quickly. It is not credible that a lawful, balanced process could be completed in such short order. A proper investigation into blacklisting should take weeks, even months, involving witness statements, evidence review and independent oversight.

The speed of Birmingham City Council’s response suggests something quite different. It looks less like a search for truth and more like an attempt to mark its own homework and award itself a clutch of gold stars, glitter and all. In doing so, it failed the basic test of transparency.

The council cannot claim openness while investigating itself behind closed doors. Nor can a solicitor-councillor preside over such haste without questioning its fairness. The people of Birmingham deserve more than a press release and a pat on the back. They deserve justice carried out in full daylight.

A political contortion

It may be tempting to call this hypocrisy, but it feels more like political calculation. His public break with Unite in March was convenient for a Labour administration under pressure: Birmingham was bankrupt, the bins were overflowing, and the optics of a combative union did not help. His resignation drew a line between reasonable council and militant strikers.

Now that the accusation has reversed, that the council itself may be intimidating workers, any strong statement risks implicating his own officers. Silence, politically speaking, is safer, but ethically it is indefensible.

The councillor who quit his union because he said its members were bullying now presides over a service accused of bullying its own workforce. The shouting has stopped, not because the principle changed but because power did.

A tale of two Mahmoods

There seem to be two Majid Mahmoods. One, the 2019 version, Corbyn’s man in Birmingham, refused to use anti-union laws and stood shoulder to shoulder with workers. The other, today’s lawyer-politician, presides over an operation accused of punishing them.

The first found his moral voice in opposition to power; the second appears to have misplaced it in defence of it. That shift mirrors Birmingham’s wider decay, not just rubbish in the streets but values swept aside in the corridors of power.

Right of reply

In the spirit of fairness, I would be delighted to include Councillor Majid Mahmood’s own response to these matters. He has my number and is welcome to call or email me at any time to share his side of this distressing issue.

The public deserves to hear not only from the strikers and agency workers but from the man ultimately accountable for the service now under fire.