WHEN WILL THE WORLD CATCH UP ..?

The Grammys are not about the best music. They never have been. They are about the "right" kind of music, the sort made by the "right" kind of people.

WHEN THE WORLD CATCHES UP

How the Grammys prove that posh people still decide what counts as good

The Grammy shortlist arrives this month, that quiet moment when the industry decides who will be allowed to call themselves the best come February. The winners will not be named until 9 February 2025, but the real game is already under way, the lobbying, the favours, the polite back-scratching that decides who gets a seat at the table. The result is all but set, some would argue!

It is the same pantomime every year. There will be glitz, false modesty, crocodile tears, and the kind of speeches that make the average human want to throw something heavy at the telly. And once again there will be that stunned expression when the wrong people win, the polite disbelief when true innovation is quietly ignored.

But here is the thing. The Grammys are not about the best music. They never have been. They are about the right kind of music, the sort made by the right kind of people. The Grammys are the great cultural mirror of the establishment, where taste is just another word for class.

And if you want proof, look no further than the Midlands.

The factory floor of world music

From the foundries and terraces of Birmingham, Coventry, and Dudley came artists who did not just make music, they invented entire genres.

Black Sabbath, four lads from Aston, Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler, and Bill Ward, built heavy metal from the sound of their own environment, industrial noise, sweat, and the clang of a world in decline. Their riffs came from factory hum. Their rhythm came from machines. Their lyrics came from working-class philosophy, life as lived, not as imagined in art school.

For decades, the establishment, both British and American, looked down its nose at them. Sabbath were called unrefined, barbaric, not real music. Then, thirty years later, the Grammys handed them a token gong for Iron Man (Live), a pat on the head for the band that had already changed the planet.

UB40 did the same for reggae. They made it British. They sang about unemployment, food banks, and real life with horns and harmony. And what did they get? No Grammy wins. No MBEs. No royal nods. No warm handshake from the Palace.

But what the establishment never understood is that UB40’s story was not one of imitation. It was one of integration. They did not steal reggae, they wove it into British life, giving it new meaning without losing its soul.

They built a bridge from Birmingham to Kingston, recording and performing with Jamaican artists, supporting local studios, and ensuring that the original songwriters behind their hits, many forgotten by the industry, finally received credit and payment. Their Labour of Love albums did not just celebrate classic reggae, they revived it, bringing a generation of Caribbean musicians back into the spotlight.

While polite culture in London was still treating reggae as a passing novelty, UB40 were treating it as something sacred, a shared voice for ordinary people across continents.

Led Zeppelin took the same Midlands grit and turned it into something mythic. They forged blues, folk, and thunder into a sound that shook the world, yet the Grammys never once recognised them in their prime. Not one award during the years they were redefining rock itself.

And here is the kicker. It was Led Zeppelin who gave Britain the sound of Top of the Pops, the very theme music of the nation’s own musical revolution. Week after week, millions of households tuned in, entire families, living rooms, pubs, all hearing that unmistakable riff as the curtain lifted on British pop. For decades, the establishment used Led Zeppelin to announce the sound of the nation, while pretending not to hear them.

Only much later did the Recording Academy come knocking, handing out a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005 and a belated Best Rock Album for Celebration Day in 2014. By then the world had already learned to kneel at their altar. The Grammys, as usual, simply caught up.

Judas Priest, another Birmingham outfit, helped define metal’s sound and look. Still no honours.

The Specials, from Coventry, the heartbeat of Two Tone and the living sound of multicultural Britain, were also ignored. Too political. Too sharp. Too real.

ELO, fronted by the symphonic wizard Jeff Lynne, were too pop for the snobs, too clever for the pop crowd.

Duran Duran, Birmingham’s stylish sons, redefined global pop and MTV itself. Still, the Grammys stayed quiet.

And here is the beautiful irony. While America was handing out awards to polite interpretations of rebellion, the Midlands was busy making the real thing.

Posh people still decide what is good

Whether it is the Grammys in Hollywood or the gongs from Buckingham Palace, the same rule applies. If it is popular, it cannot be good.

That is how the establishment thinks.

They want art to be distant, not democratic. They need it to come from the right sort of person, ideally someone with a trust fund, a double-barrelled surname, and an ironic relationship with the working class.

But the Midlands does not do irony. It does graft. It does truth. It does music you can feel in your boots.

When Sabbath wrote War Pigs, they were not looking for a concept album. They were holding a mirror to a country that sent poor men to die in rich men’s wars. When UB40 sang One in Ten, they did not need metaphors. They had the dole queue outside the studio window.

That is what makes the establishment uncomfortable, the idea that real people can make real art.

So the Crown pins medals on the safe ones. The Grammys hand trophies to those who play the game. And the innovators, the dangerous, loud, untidy ones, get the slow clap of history.

And then there was Joan

But there is always one who slips through early.

Joan Armatrading, raised in Birmingham, quiet, precise, and utterly original, became the first British female artist ever nominated for a major Grammy.

No marketing gimmicks, no record-label puppeteers, no pose.

She just wrote songs that cut straight to the bone, Me Myself I, Love and Affection, Willow, and she did it without compromise.

Joan was the exception that proved the rule. You cannot silence authenticity forever. It has a way of walking through closed doors, quietly, and taking a seat at the table without asking permission.

The Grammy paradox

Here is the truth. The Grammys are not a measure of quality. They are a record of when the establishment finally gives in.

Black Sabbath did not suddenly become great in 2000. They had been great since 1970, maybe 1968.

UB40 did not need a statue to matter. They had already soundtracked people’s lives.

Led Zeppelin did not need validation from a committee. They had already written the DNA of modern rock.

And that is the Midlands story in miniature. This region has always been ahead of the applause. It builds, it creates, it leads, and only when it is safe do the tastemakers follow.

The Grammys, the royal gongs, the industry back-slapping, they all come from the same polite instinct, to reward rebellion only once it has gone quiet.

Steel over gold

So when the next round of Grammys hits in February and the usual polished names take the stage, just remember this.

Britain’s best music did not come from the coasts. It came from the heart.

From the noise of Birmingham, the sweat of Aston, the pulse of Coventry.

It came from people who did not need permission to be brilliant.

The Grammys hand out gold.

The Midlands made steel.

This is the full piece, with every thread of political stitching intact, running on midlandsGRIT, where the words have space to breathe and the seams are left deliberately unpolished.

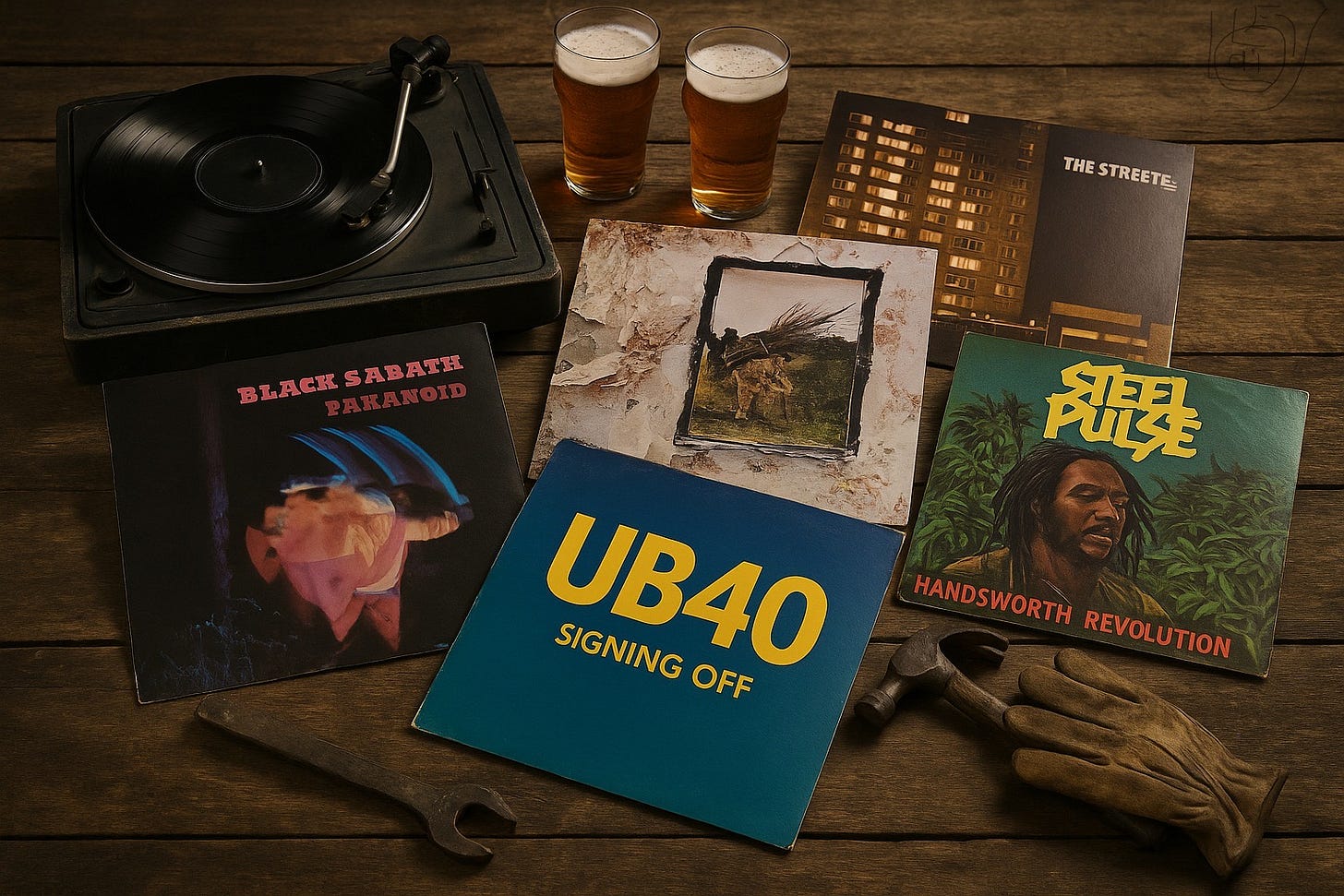

ps - apologies to so many, I simply had no room for in this article, Mike Skinner of the Streets (let's face it the American establishment didn’t know what to do with a bloke from Druid’s Heath rapping about overdrafts, kebabs, and existential dread in a Brummie accent) also apologises to Basil, Grizzly, Alphonso (Steel Pulse) and so many other truly magnificent musical stars - genuinely love and respect you all - “darlings” …